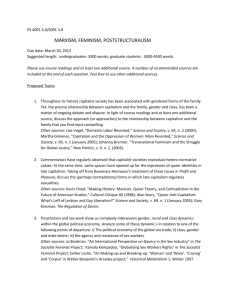

Weber-Shackelford-Soper-Neg-UNLV

advertisement