Creation of Express Trusts

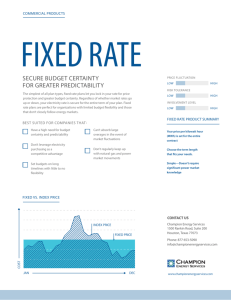

advertisement

Creation of Express Trusts Assoc Prof Cameron Stewart Ways to create a trust 1. by declaration, where a titleholder expresses his or her intention to hold their property on trust for another; 2. by transfer, where title is transferred to a person with instructions that it be held on trust for another; the transfer can occur either via an inter vivos transaction (which is generally referred to as a ‘settlement’) or post mortem (by will); and 3. by direction, where the beneficiary of an existing trust directs the trustee to hold his or her interest on trust for another. The three certainties Intention Subject matter/Property Beneficiaries/Objects Without all three the trust will fail Certainty of intention An express trust will not be valid unless it is clear that the creator has intended to create a trust. NB: resulting and constructive trusts do not have to satisfy certainty of intention. The requirement of certainty of intention does not mean that the creator has to be fully aware of the law of trusts before they can be found to have intended to create a trust Certainty of intention Because of the focus on the creator’s intention it is possible to create a trust without using the words ‘trust’ or ‘trustee’ The intention to create a trust can also be inferred from conduct Commissioner of Stamp Duties v Joliffe (1920) 28 CLR 178 the trust was not valid even though express words of trust were used Foley v Foley [2006] QSC 347 La Housse v Counsel [2008] WASCA 207 Certainty of intention Must be an intention to create a trust at that time In Harpur v Levy (2007) 16 VR 587, a deceased person had attempted to create a trust prior to death, but the trust was not intended to commence until a later time. Death unkindly intervened. The Victorian Court of Appeal found that the deceased’s intentions meant that the trust had never been constituted. Re Armstrong (dec’d) two investment accounts had been deposited by the settlor in a bank for 2 years. The bank manager was instructed to give the principal sums to the settlor’s sons when the investments matured. Interest was to be paid to the creator. The court found that there was an intention to create a trust for the sons over the capital amounts, even though those beneficial rights were postponed until the investments matured. Certainty of intention The burden of proof in cases where the intention of the creator is questioned, lies on the person who alleges that a trust was intended Inter vivos: oral and written evidence allowed Certainty of intention Parol evidence rule will not apply in situations where: 1. The disposition of the property that constitutes the trust is not required to be in writing (eg the disposition was of personal property): Boccalatte v Bushelle [1980] Qd R 180; 2. The document was not intended to be a complete expression of the transferor’s intention: Star v Star [1935] SASR 263; or 3. The document is ambiguous, Lutheran Church of Australia v Farmers Cooperative Executors & Trustees Ltd (1970) 121 CLR 628; Boranga v Flintoff (1997) 19 WAR 1, or created in circumstances of fraud, duress or mistake. Certainty of intention In cases of post mortem trusts, the law restricting extrinsic evi¬dence in the interpretation of a will also applies in addition to the parol evidence rule if the creator transfers property and expresses a motive, hope or expectation that the property will be used in a particular way, the condition will be viewed as precatory and impose no obligation. A mere intention to create a trust which is not acted upon will not satisfy the requirement of certain intention: Chang v Tjiong [2009] NSWSC 122 Quistclose trusts Trusts and debt Mutual intention of settlor and trustee? Barclays Bank Ltd v Quistclose Investments Ltd [1970] AC 567; [1968] 3 All ER 651 The mutual intention of the parties can be discerned from the language employed by the parties, the nature of the transaction and the relevant circumstances attending the relationship between them Quistclose trusts Sole intention of trusee? Re Kayford Ltd (in liq) [1975] 1 All ER 604 Stephens Travel Service International Pty Ltd (receivers and managers appointed) v Qantas Airways Ltd (1988) 13 NSWLR 331 Beneficiaries of life insurance policies In the Matter of An Application By Police Association of South Australia [2008] SASC 299 Certainty of subject matter An express trust cannot exist without trust property. The trust property must therefore be reasonably identifiable or ascertainable at the time the trust is created. This requirement of identifiability is known as ‘certainty of subject matter’ Certainty of subject matter One of the equitable maxims that is used here is ‘that which is not certain is capable of being rendered certain’. As long as it is possible to piece together the clues to determine the identity and quantum of the property it will be sufficiently certain Re Golay’s Will Trusts [1965] 2 All ER 660, a gift of ‘reasonable income’ was upheld because the words ‘reasonable income’ were, in the circumstances, capable of objective determination. In Estate of Chau (dec’d) [2008] QSC 156, ‘a trust over any money that I may have including any bank accounts’ was said to include a wealth management account which contained units in a unit trust with a bank. Certainty of subject matter Problems can occur when the trust property is part of a number of identical items, for example, ‘5% of 950 shares’. If the subject matter has not been specifically identified the trust is uncertain: Herdegen v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1988) 84 ALR 271 White v Shortall [2006] NSWSC 1379 Future property cannot be held on trust: Re Rule’s Settlement [1915] VLR 670. Certainty of objects A trust will fail if the beneficiaries are not identified with sufficient certainty. This is sometimes known as ‘the beneficiary principle’ There are two exceptions to this rule. The first exception is charitable trusts. The second exception is a particular anomalous group of trusts for animals The level of certainty required by the beneficiary principle changes subject to whether the trust is a fixed trust or a discretionary trust Fixed trusts and certainty In a fixed trust the beneficiaries must be identifiable in such a way as to allow the court to draw up a complete list of the beneficiaries at the time their beneficial interests come into effect : Re Gulbenkian's Settlements [1970] AC 508; Lempens v Reid [2009] SASC 179; Prosper v Wojtowicz [2005] QSC 177 Problems can occur when the list of possible beneficiaries is extremely long and the job of discerning the identity of the beneficiaries cannot be completed at the time the trust comes into effect: West v Weston (1998) 44 NSWLR 657 Fixed trusts and certainty Once the identity of the beneficiaries has been ascertained the fact that it is difficult to find the whereabouts or continued existence of the beneficiaries does not affect the certainty of the disposition. Trustees can always apply to the court for directions or pay the missing beneficiary’s share into court Certainty of beneficiaries in discretionary trusts It should be recalled that discretionary trusts, or trust powers, are forms of trust whereby the trustee is given the discretion to choose the beneficiaries.In cases where the trustee’s discretion is unfettered the power of the trustee is called a general power. Note, however, that in such circumstances the trustee will be unable to use the power for his or her benefit. If the trustee is permitted to appoint themselves under a general power then there will be no trust as such a power is tantamount to ownership. Where the trustee is allowed to choose from beneficiaries of a particular class, the power is referred to as a special power. The trustee’s power might also be an intermediate or hybrid power where the trustee is allowed to choose beneficiaries as long as they are not part of a particular class Certainty of beneficiaries in discretionary trusts In Re Baden’s Deed Trusts; McPhail v Doulton [1971] AC 424 ‘criterion certainty’ Certainty of beneficiaries in discretionary trusts Unincorporated associations Radmanovich v Nedeljkovic (2001) 52 NSWLR 641; Leahy v Attorney General (NSW) [1959] AC 457; In The Estate of Dulcie Edna Rand (dec'd) [2009] NSWSC 48; Hanchett-Stamford v Attorney-General [2008] EWHC 330 The rule against delegation of testamentary power: Tatham v Huxtable (1950) 81 CLR 639 Complete constitution of an express trust ‘Complete constitution’ generally refers to the irrevocable transfer of the trust property and the creation of the beneficial interest. executed trust which has been completely constituted executory trust, which is merely an uncompleted agreement to create a trust Complete constitution of an express trust An executory trust that is not supported by consideration cannot be specifically performed, nor can there be an order of part performance in relation to it. This is because equity will not assist a volunteer. However, this maxim does not apply once the trust is executed. An executed trust is enforceable, even at the suit of a volunteer, because the trustee has been fully burdened with fiduciary responsibilities Complete constitution of an express trust Declarations of trust Legal personal property - no writing Equitable personal property – writing - Adamson v Hayes (1973) 130 CLR 276 Land – writing Wratten v Hunter [1978] 2 NSWLR 367, a son was given land by his dying father. At the funeral of the father the son declared that he was going to hold the land on trust for the other members of the family. However, his brother and sister later were unsuccessful in enforcing the trust as the trust was not evidenced in writing. Nor could they seek remedies in part performance as they were volunteers. ‘Manifested and proved in writing’? Pascoe v Bensch (2008) 250 ALR 24 Department of Social Security v James (1990) 95 ALR 615 Marchesi v Apostoulou [2006] FCA 1122 Complete constitution of an express trust Creation by transfer Trusts created by transfer will be executed when the title of the trust property has been completely and irrevocably transferred to the trustee Inter vivos – perhaps writing or Milroy Post mortem - wills Complete constitution of an express trust Creation by direction A trust is created when the beneficiary of an existing trust directs the trustee to hold his or her interest on trust for another. This is a disposition of an existing equitable interest and, as such, needs to be evidenced in writing An agreement to create a trust at a later time In Queensland the Court of Appeal has held that executory contracts for interests in land are covered by the requirements for writing in the Property Law Act 1974 (Qld), s 11(1)(b): Riches v Hogben [1986] 1 Qd R 315; Theodore v Mistford. ISPT Nominees Pty Ltd v Chief Commissioner of State Revenue (2003) 12 BPR 22, 941 Halloran v Minister Administering National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (2006) 229 CLR 545; 224 ALR 79 Sorna Pty Ltd v Flint [2000] WASCA 22 at [7] Abjornson v Urban Newspapers Ltd [1989] WAR 191 at 200. Thompson v White a joint venture agreement involved the purchase of property in the name of one of the parties with a view to renovating it and selling it. The profits were to be split between the parties. The agreement did not purport to immediately create any legal or equitable interest in the property in favour of the other parties to the joint venture. On that basis, the New South Wales Court of Appeal found that there was no requirement of the agreement to be in writing. Baloglow v Konstanidis [2001] NSWCA 451 Khoury v Khouri (2006) 66 NSWLR 241 Secret trusts Form of testamentary trust fully secret trusts where there is no record of the testator’s intention to create a trust in the will half secret trusts, where the testator indicates his or her intention that the gift is not to be held beneficially, but is held subject to some private instruction that has been communicated by the testator Secret trusts 1. the testator must intend to subject the donee to an obligation of trust; 2. the testator must communicate the intention to the donee; and 3. the donee must accept the obligation before the testator’s death. Secret trusts The nature of the secret trust has been subject to long debate. On the one hand, a secret trust can be understood as part of the will, on the other, the trust can be seen as an independent trust that exists separately from the will. It is now accepted that the secret trust is the latter What is the trust property of a secret trust? Contsructive? Problem Eric was a wealthy fashion designer, and was happily married to Stephanie. During the Vietnam War, while stationed at Darwin, Eric had an affair with Brooke. As a result of that affair Eric and Brooke had a son named Eric Jnr. Eric’s past was unknown to Stephanie. Eric was concerned that Brooke and Eric Jnr were satisfactorily provided for in his will. Eric thus made a will, in 1980, and clause 7 of the will read as follows: Problem I leave $500,000 to my son Ridge feeling confident that my express wishes in relation to this money will be carried out. By clause 15 of Eric’s will, Stephanie was named as beneficiary of the residue of his estate. Problem On 1 April 1997 Eric showed his will to his son Ridge and handed him a sealed envelope. He said to Ridge: ‘I want you to carry out the instructions contained in this letter after I die. You are not to tell your mother about it.’ Ridge said nothing in response but nodded to indicate that he agreed to abide by his father’s wishes. On 1 May 1997, Brooke died in an automobile accident. Upon hearing of the news of Brooke’s death Eric suffered a heart attack and eventually died on 1 June 1997. Problem After his father’s death Ridge opened the envelope he had been given in April 1990. In the letter Eric stated that the $500,000 referred to in clause 7 of his will was to be held on trust for Brooke. In trying to locate Brooke, Ridge discovered that she had died and had left a will appointing her son Eric Jnr as executor and beneficiary of her entire estate. Ridge seeks your advice as to what is to happen to the $500,000 referred to in clause 7 of Eric’s will.