So, how did we get Marbury v. Madison in the first place?

advertisement

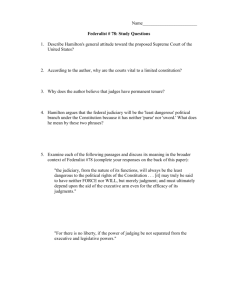

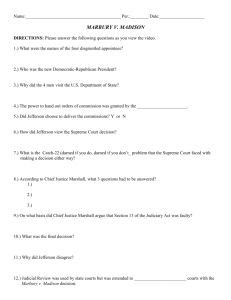

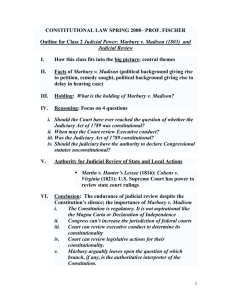

Marbury v. Madison: The Beginnings of Judicial Review Part 1: John Marshall and the Law The Constitution says that the United States shall have a Supreme Court, but the rest of the details are rather fuzzy. In other words, nowhere in the Constitution does it specifically say whether the Supreme Court can declare a law unconstitutional. For that power, we have to turn to one of the giants of American history--John Marshall. Marshall was not the first Chief Justice of the United States. (That was John Jay.) Marshall was, however, the first very influential Chief Justice. His decisions, beginning with Marbury v. Madison, set the tone and much of the legal precedent that is still being followed by Supreme Court justices today. In very simple terms, Marbury v. Madison, is important because it was the first time a law of Congress was ever declared unconstitutional, or in conflict with the Constitution. If the Constitution is the law of the land and something is conflict with that law of the land, then that something is illegal. Part 2: A Little Background So, how did we get Marbury v. Madison in the first place? Well, it all goes back to party politics really. Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson were the leaders of two political parties. Hamilton led the Federalists; Jefferson led the Democratic-Republicans. After George Washington retired, his vice-president, John Adams, succeeded him. Adams ran for election in 1800, and he was opposed by his vice-president, Thomas Jefferson. Adams was a Federalist. Jefferson was elected in November 1800. At that time, the new president didn't take office until March 4 of the following year. So Adams had a few months to try to get things done before Jefferson took over. In the time between the election and the time that Jefferson took office, the lame duck Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1801, which gave the President the power to appoint more federal judges. One of the things Adams tried to do, under this new law, was get as many Federalist judges appointed as he could. As March 4 drew near, Adams got more and more concerned with doing this. He kept appointing judges long into the night on March 3. These were known as the "Midnight Judges." One of these "Midnight Judges" was William Marbury, who was named to be justice of the peace for the District of Columbia. Now, the normal practice of making such appointments was to deliver a "commission," or notice, of appointment. This was normally done by the Secretary of State. Jefferson's Secretary of State at the time was James Madison. Jefferson didn't want all those Federalist judges, so he told Madison not to deliver the commission. Part 3: History in the Making Now it's important to remember that John Marshall was a Federalist and that things in the Judicial Branch were a lot more political than they are now. Marshall wanted to support Adams, his fellow Federalist, but he had to follow the law. Or did he? One of the things that the new Congress, controlled by Jefferson's Democratic-Republican party, did was pass the Judiciary Act of 1802, which reversed the Federalist-approved Judiciary Act of 1801, turning the clock back to 1789. Marshall and the rest of the Supreme Court decided that the power to deliver commissions to judges, since it was part of the Judiciary Act of 1789 and not part of the Constitution itself, was in conflict with the Constitution and, therefore, illegal. Further, the entire Judiciary Act of 1789 was illegal because it gave to the Judicial Branch powers not granted to it by the Constitution. So, it appears that Marshall sided with his political enemies, right? Marbury, a Federalist, didn't get to be justice of the peace in the District of Columbia. Adams was probably quite angry because his commission was denied. Jefferson and Madison were probably quite happy because they got to name their own friendly justice of the peace. But Marshall gave to the Supreme Court a whole new power: the power to throw out laws of Congress. So, no matter how many laws Thomas Jefferson and his Democratic-Republicans passed and made into law, the Supreme Court always had the ultimate check on that legislative and executive power. John Marshall, in appearing to lose the political battle, won the political war. Federal Judiciary Act (1789) The founders of the new nation believed that the establishment of a national judiciary was one of their most important tasks. Yet Article III of the Constitution of the United States, the provision that deals with the judiciary branch of government, is markedly smaller than Articles I and II, which created the legislative and executive branches. The generality of Article III of the Constitution raised questions that Congress had to address in the Judiciary Act of 1789. These questions had no easy answers, and the solutions to them were achieved politically. The First Congress decided that it could regulate the jurisdiction of all Federal courts, and in the Judiciary Act of 1789, Congress established with great particularity a limited jurisdiction for the district and circuit courts, gave the Supreme Court the original jurisdiction provided for in the Constitution, and granted the Court appellate jurisdiction in cases from the Federal circuit courts and from the state courts where those courts rulings had rejected Federal claims. The decision to grant Federal courts a jurisdiction more restrictive than that allowed by the Constitution represented a recognition by the Congress that the people of the United States would not find a full-blown Federal court system palatable at that time. For nearly all of the next century the judicial system remained essentially as established by the Judiciary Act of 1789. Only after the country had expanded across a continent and had been torn apart by civil war were major changes made. A separate tier of appellate circuit courts created in 1891 removed the burden of circuit riding from the shoulders of the Supreme Court justices, but otherwise left intact the judicial structure. With minor adjustments, it is the same system we have today. Congress has continued to build on the interpretation of the drafters of the first judiciary act in exercising a discretionary power to expand or restrict Federal court jurisdiction. While opinions as to what constitutes the proper balance of Federal and state concerns vary no less today than they did two centuries ago, the fact that today’s Federal court system closely resembles the one created in 1789 suggests that the First Congress performed its job admirably. (Information excerpted from The Judiciary Act of 1789. National Archives and Records Administration: Washington, DC, 1989.) Judiciary Act of 1801, 2 Stat. 89 (1801) Facts about the Judiciary Act of 1801, passed in February of 1801: Also known as the “Midnight Judges Act.” Passed by an outgoing Federalist Congress, the act eliminated the circuit riding duties of Supreme Court justices. Created new independent circuit courts – and judgeships – which the Federalist Adams administration proceeded to pack with new appointees. Reduced the number of Supreme Court justices from six to five. Answers.com > Wiki Answers > Categories > Law & Legal Issues > Children and the Law > Emancipation and Ages for Moving Out > What is judicial review and how is it used? What is judicial review and how is it used? In: Emancipation and Ages for Moving Out, US Supreme Court [Edit categories] Answer: Judicial review is the power of the courts to review laws, treaties, policies or executive orders relevant to cases before the court and nullify (overturn) those that are found unconstitutional. Judicial Review is not an American invention, but a standard part of British common law that became part of the legal process in the United States. The first recorded use under the US Constitution was in 1792, when the circuit courts found an act of Congress related to military veterans unconstitutional. Congress rewrote the law -- without protest -- in 1793. The US Supreme Court first exercised judicial review 1796, in the case of Hylton v. United States, although the rationale for using it had been laid in Federalist No. 78. Hylton v. United States was the first instance in which the Supreme Court evaluated the constitutionality of a federal law. In Hylton, the legislation, a carriage tax, was upheld. In a later case that year, Ware v. Hylton, the Ellsworth Court determined The Treaty of Paris took precedence over an otherwise constitutional state law and nullified the law. The US Supreme Court case most often credited with affirming the doctrine of judicial review is Marbury v Madison, (1803) in which Chief Justice John Marshall declared Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789 unconstitutional. This was the first time the Supreme Court overturned federal legislation. It greatly strengthened the power of the judicial branch, which had thus far been weaker than the other two. Judicial review in the United States also refers to the power of the Court to review the actions of public sector bodies in terms of their lawfulness, or to review the constitutionality of a statute or treaty, or to review an administrative regulation or executive order for consistency with either a statute, a treaty, or the Constitution itself. Judicial review is part of the United States' system of checks and balances on government. The Supreme Court has the power to review acts of the Legislative (Congress) and Executive (Presidential) branches to ensure they don't become too powerful or abrogate the Constitutional rights of the country's citizens. Examples of Supreme Court Cases Involving Judicial Review Hylton v. United States, 3 US 171 (1796) Ware v. Hylton, 3 US 199 (1796) Marbury v. Madison, 5 US (Cranch 1) 137 (1803) Dred Scott. v. Sanford, 60 US 393 (1857) West Virginia v. Barnette, 319 US 624 (1943) Brown v. Board of Education, 347 US 483 (1954) Baker v. Carr, 369 US 186 (1962) Roe v. Wade, 410 US 113 (1973) United States v. Nixon, 418 US 683 (1974)