Araby notes - WordPress.com

advertisement

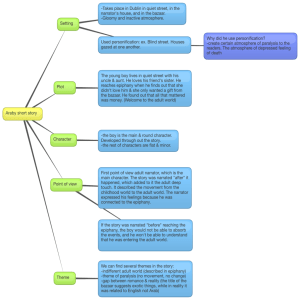

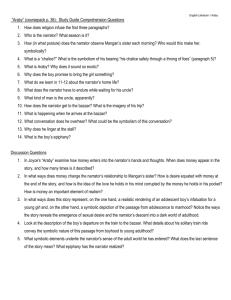

Araby As with "The Encounter," this story deals with longing for adventure and escape, though here this longing finds a focus in the object of the narrator's desire, Mangan’s sister. The title, "Araby," also suggests escape. To the nineteenth-century European mind, the Islamic lands of North Africa, the Near East, and the Middle East symbolized decadence, exotic delights, escapism, and a luxurious sensuality. The boy's sexual desires for the girl become linked to his fantasies about the wonders that will be offered in the Orientalist bazaar. Again the unfamiliar and different, the non-Dublin, gains a positive connotation. The third story of the collection is the last story with a first-person narrator. It continues with the ages-of-life structure: we have had young boys for our protagonists in both "The Sisters" and "An Encounter," and here we have a boy in experiencing his first passion. As the boy is becoming a man, the bazaar becomes symbolic of the difficulty of the adult world, in which the boy proves unable to navigate. His boyish fantasies are dashed by the realities of life in Dublin. The first three stories are all narrated in the first-person, and they all have nameless boys as their narrators. All three narrators seem sensitive and intelligent, with keen interests in learning and a propensity for fantasy. Joyce was still in his early twenties when he wrote Dubliners and clearly drew on his own personal experiences more directly in writing these three tales. The namelessness of all three boys also encourages interpreters to identify them with Joyce, although from an interpretive point of view this move does little to illuminate the stories. "Araby"'s key theme is frustration, as the boy deals with the limits imposed on him by his situation. The protagonist has a series of romantic ideas, about the girl and the wondrous event that he will attend on her behalf. But on the night when he awaits his uncle's return so that he can go to the bazaar, we feel the boy's frustration mounting. For a time, the boy fears he may not be able to go at all. When he finally does arrive, the bazaar is more or less over. His fantasies about the bazaar and buying a great gift for the girl are revealed as ridiculous. For one thing, the bazaar is a rather tawdry shadow of the boy's dreams. He overhears the conversation of some of the vendors, who are ordinary English women, and the mundane nature of the talk drives home that there is no escape: bazaar or not, the boy is still in Dublin, and the accents of the vendors remind the reader that Dublin is a colonized city. There is also a socioeconomic theme too, directed towards exemplifying the limitations of the lower class. The boy has arrived too late to do any serious shopping, but quickly we see that his tardiness does not matter. Any nice gift is well beyond his price range. We know, from the description of the boy's housing situation and the small sum his uncle gives him, that their financial situation is tight. Though his anticipation of the event has provided him with pleasant daydreams, reality is much harsher. He remains a prisoner of his lower social class and his city. Key Quotations Explained: We can often see elements of fantasy and imagination through the personification of houses, where a child’s perspective is able to bring objects to life. “The other houses of the street, conscious of decent lives within them, gazed at one another with brown imperturbable faces.”(21) In this story the imaginative powers of a child are seen as interesting and powerful, where their perception is able to bestow life and intelligence unto inanimate objects. The perspective of imaginative children is even able to bestow emotion unto the houses, “When we met in the street the houses had grown somber.” (21) The personification of these houses can also be seen as foreshadowing of their maturation, or a reflection of their maturing selves. They are portrayed as thoughtful, conscious, and somber beings, void of imagination and playfulness. Joyce makes frequent use of the elements of sound, light and dark, “these noises converged in a single sensation of life for me: I imagined that I bore my chalice.” (23) In this case sound is a signifier of the positive, a proof of life and all of its exciting and adventurous sensations. It is also worth noting the chalice, where in the first story, ‘The Sisters’, the chalice is broken, symbolic of the priests religious death and foreshadowing his literal death. It can also be seen to symbolize the priests shattered sate of being, it is already hinted that he was emotionally unstable, and that he was accused of selling blessings or pardons, the broken chalice then is representative of his broken spiritual state. In this third story the Chalice is whole though, and being seen positively and associated with the holy grail it gains connotations of adventure and romance. It might also be interesting to compare these two stories and chalices, as the young boy on the cusp of manhood imagines a holy chalice, like something out of a quest the chalice in ‘The Sister’s’ is broken, and belonged to an old man now dead. Back to the subject of sound, light and dark though… We see a progression from light to total darkness in this story, mimicking the state of the boy narrator as he moves from an imaginative, hopeful, child to a disappointed and unhappy young man. Early on in the story we see the young narrator playing in the street with his friends, “We played till our bodies glowed.” (21). Their youthful state of play shows them glowing with light, illuminated by their child’s play. They can also be seen as pure, bright and glowing in their childlike innocence. We can also see light and darkness as representative of transition, “We left our shadows and walked up to Mangan’s steps resignedly.”(22) Where the children are stepping out of their roles as children, out of their shadows, and approach her steps with hesitation, no longer entirely children. Later we see light as symbolic of hope, hope for the future, of romance and possibility, “She was waiting for us, her figure defined by the light from the half opened door.” (22) Mangan’s sister is defined by light, symbolic of the narrator’s perspective of her, an object of desire, an element of fantasy, a hope of something exciting and interesting. The fact that the door is half open as well is symbolic, they are not yet denied this hope, the door is half open, but they are not yet privy to that hope as the door is also half closed. A half closed door is also representative of their transition state, they are between being boys and men, as the door it between being closed and shut. As the story progresses and the hope and imaginative perspective is slowly dashed we see less of this ‘light’ and more examples of darkness. This is most evident in the narrators arrival at the bazaar, where his idealized and imagined world is first crushed, “Nearly all of the stalls were closed and the greater part of the hall was in darkness. I recognized a silence like that which pervades a church after a service.” (26) We also see a reemergence in sound, this time and absences of sound. As well, the majority of a hall is showed in darkness, showing how much of the narrators hope has been crushed be the realism of Dublin, that the bazaar is still very much Dublin, not exotic, not exciting. The more of the bazaar he sees the more he realizes this and the more we see of darkness, “The upper part of the hall was now completely dark.” (27). This darkness exemplifies this loss of hope (loss of light) and crushing, negative state that realism has on the boy, where realism and Dublin are symbolized by darkness. Hope & Childhood Innocence = Light Realism & Dublin = Darkness We see a further example that darkness and lack of sound is associated negatively, “One evening I went into the back drawing-room in which the priest had died. It was a dark rainy evening and there was no sound in the house.” (23) The sentence starts with the mention of the room in which the priest had died, leading us to associate death with the later mention of dark evening and no sound. The quote from page 23 is of interest, where the narrator says, “my body was like a harp and her words and gestures were like fingers running upon the wires” (23) In this case the narrator sees himself as an instrument, an inanimate object capable of making music. Music in the story, or sound, has a positive association but the idea that he is unable to produce music without her playing him foreshadows his powerlessness over his own state of being. It also points towards the idea that he is being controlled by desire, and that his desire is capable of producing music, desire then is seen as positive but also reliant upon outside elements. CLOSE READING PAGE 24: “I answered few questions in class. I watched my master’s face pass from amiability to sternness; he hoped I was not beginning to idle. I could not call my wandering thoughts together. I had hardly any patience with the serious work of life which, now that it stood between me and my desire, seemed to me child’s play, ugly monotonous child’s play.” (24) In this quote, the young boy of “Araby” has just spoken with Mangan’s sister, and now finds himself entirely uninterested and bored by the demands of the classroom. Instead, he thinks of Mangan’s sister, of the upcoming bazaar, and of anything but what rests before him. “I could not call my wandering thoughts together.” This scene forecasts the boy’s future frustration with the tedious details that foil his desires, and it also illustrates the boy’s struggle to define himself as an adult, even in the space of the classroom structured as a hierarchy between master and student. Just as mundane lessons, “hardly any patience with the serious work of life”, obstruct the boy’s thoughts, by the end of the story everyday delays undermine his hopes to purchase something for Mangan’s sister at the bazaar. In both cases, monotony prevents the boy from fulfilling his desires. This scene articulates the boy’s navigation between childhood and adulthood, “the serious work of life which, now that is stood between me and my desire, seemed to me child’s play.” He sees the routine boredom of school as child’s play—it is easy, unengaging, and repetitive. Desire, on the other hand, is inspirational and liberating. His thoughts, after all, wander everywhere, rather than remain fixed to the place they should be. Ironically yearning for the freedom of adulthood, the boy remains chained to the predictability of childhood. The irony underpinning the word idle reflects the hypocrisy of this situation, and as such forms one of the moments in the narrative when the subject’s voice speaks through the detached third person. What exactly, the passage asks, is idle about excited desire? There is nothing idle about this passage, in fact it is the opposite at the boy is unable to gather his thoughts, he is overwhelmed with thoughts os adventure, imagination and desire.