Ch. 20. Statute of Frauds and the Parol Evidence Rule

advertisement

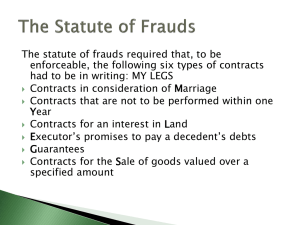

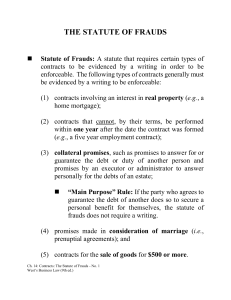

Chapter 20: Statute of Frauds and Parol Evidence Rule Elizabeth Necka, Emilie Baugh, and Julie Sztukowski Edited by Nikki Meltabarger I. Statute of Frauds Oral contracts are typically binding, though it is sometimes difficult to prove their existence if they are challenged in court. However, some types of agreements are only valid and enforceable when they are in writing. These contracts are covered by the Statute of Frauds. If a type of contract (often abbreviated K) is listed in the Statute of Frauds, it is only enforceable if it is written. A. Real Estate 6 Real estate contracts are the first provision in the Statute of Frauds. Any contract pertaining to an exchange of land or real estate property must be in 1. Real estate Ks writing. These include the following: 1. 2. Long term Ks Mortgages, 2. Long term leases, which 3. Someone else’s debt pertain to a period of one year or greater, 4. Debt of deceased 3. Easements, which pertain to the 5. Dowry permanent right to use another party’s 6. $500+ in goods property. The only exception to this element of the Statute of Frauds is substantial performance on the grounds of the contract. Substantial performance can be payment on the property, buyer possession of the property, or buyer improvement on the property. Most states require two or three of the conditions to be met before the courts will enforce an oral contract. There are six main types of contracts that are covered by the Statute of Frauds. Consider the following scenario under the Statute of Frauds: Chapter 20 Statute of Frauds Page 1 Mike and Jim have been best friends for as long as they can remember. Even though their friendship became long distance after college--Mike lives in Washington and Jim lives in Illinois--they have maintained contact. One day, Mike decides he wants to move to California to soak up the sun and coincidentally Jim’s job forces him to relocate to Washington. Since they are best friends, the two make an oral contract. Mike tells Jim, “You can have my place.” Jim is buying the house from Mike. o Their oral contract is unenforceable. Because this is a real estate contract, it is covered by the Statute of Frauds. Jim is renting the house from Mike, but Jim is only going to live there for six months. o Their oral contract is enforceable. Although this is a real estate contract, the duration of Jim’s lease makes this an exception to the Statute of Frauds. Real estate contracts must only be in writing if they are long-term leases. Long-term leases pertain to a period of time greater than one year. Mike tells Jim that he can use a private road on his property indefinitely. o Their oral contract is unenforceable. This is a real estate contract covered by the Statute of Frauds. The contract is an easement, or an agreement between two parties stating that one party gives another party the permanent right to use some of the first party’s property. Jim bought the house from Mike, moved in, painted some rooms, and made renovations. When Mike gets too sun-burnt and wants to go back to Washington, he tries to kick Jim out, claiming their contract is voidable. o Their oral contract is enforceable. While real estate contracts must be in writing according to the Statute of Frauds, courts will typically enforce an oral deal if there is already substantial performance on the grounds of the contract. B. Long-term contracts The second provision of the Statute of Frauds pertains to long-term contracts which cannot be completed within one year of their creation. This also pertains to contracts for a service or employment which is ongoing for over a year or an unspecified amount of time that could likely be over a year. Consider this example under the Statute of Frauds: Samantha and Eleanor work as secretaries in an office and they hate paperwork. On June 1, 2009, they decide to make an oral contract. Chapter 20 Statute of Frauds Page 2 Eleanor has a quick brain for numbers and agrees to balance Samantha’s checkbook and pay her bills for her from now until December 31, 2010, when Samantha plans to have paid off her credit-cards. o Their oral contract is unenforceable. Under the Statute of Frauds, contracts that cannot be performed within one year of the date of the contract must be in writing. Because Eleanor will not complete this service until 18 months after the contract was made, there must be a written contract. Eleanor agrees to watch Samantha’s four-year-old son every Saturday, except for holidays, until the end of summer, September 1, 2009. Samantha will be employing Eleanor as a babysitter. o Their oral contract is enforceable. Because this employment period will be completed three months from when the contract is made, it does not fall into the domain of the Statute of Frauds and does not need to be in writing. Samantha and Eleanor decide to open their own Taco Bell franchise. Samantha’s husband, Chris, who works for Taco Bell, tells them they can be part of the Taco Bell franchise for the next five years. However, Chris did not clear this with his boss, gets in trouble, and tries to convince the women not to open the store. o Their oral contract is unenforceable. Franchise agreements are long-term business contracts and, therefore, need to be in writing. Samantha starts a business and because she knows Eleanor is a good worker, employs her as her Office Supervisor. When she decides she cannot afford an Office Supervisor in December of 2010, she tries to get rid of Eleanor by claiming their contract was voidable. o Their oral contract is unenforceable. Because this contract pertained to employment of over a year (if no ending date of employment is set, it is assumed that employment will last over a year), the Statute of Frauds requires it to be in writing. However, Eleanor must pay Samantha for the work she has already done. An example of a long-term oral contract can be seen in the Doherty v. Doherty case below. Chapter 20 Statute of Frauds Page 3 Doherty v. Doherty Insurance Agency, Inc. 878 F.2d 540 (1989) United States Court of Appeals, First Circuit Brothers Bill and Jim Doherty founded an insurance and real estate agency in the 1930s in Andover, Massachusetts. Bill became seriously ill in 1955. He did not want Jim to have to run the business alone in case something was to happen to him. Due to this, Bill and Jim asked their brother Joseph to join the family business. Joseph was hesitant to join because he already had a job as a superintendent of schools in Easthampton, Connecticut and feared he would lose his retirement benefits. On the business’ behalf, Jim orally offered Joseph “retirement benefits for his remaining life” equal to his salary when he retired at 65. Based upon this promise, Joseph quit his job as a superintendent and joined the family business with his brothers. In 1970 Bill retired on a full salary. In 1978 Joseph retired, receiving $2,000 a month in benefits. Finally, in 1980 Jim retired on a full salary. With the three brothers all retired, the business was left to Jim’s and Joe’s children. In 1981 a disagreement occurred between the children. Joe’s children left the business. As such, Jim’s children ceased the retirement benefits being paid to Joe. In turn, Joe sued. Jim’s children argued that under the Statute of Frauds, the oral retirement contract was unenforceable due to the fact that it took longer than one year to complete. The trial court held in favor of Joe, and Jim’s children appealed. In the opinion of Chief Judge Campbell, the oral contract in this instance was enforceable. He believes that a contract for a term of years is distinguishable from one pertaining to a lifetime of a person. The provided retirement benefits for Joe from Insurance Agency, Inc. in conjunction with the dispute of the children does not signify that the contract could not have been completed within the first year. In this case, the jury found that based upon the promise of Jim to pay include lifetime retirement benefits along with Joseph’s compensation, Joseph would “work with [the brothers] for the balance of his working days.” Had Joseph passed away with in the first year his promise to work the balance of his working days would have been fulfilled; Insurance Agency, Inc. would have fulfilled its duty of providing compensation for Joseph’s remaining life. The oral agreement between Jim on behalf of Insurance Agency, Inc. and Joseph is considered to be beyond the scope of the Statute of Frauds, and is thus enforceable under Massachusetts law. The appellate court held that this oral agreement was enforceable. Chapter 20 Statute of Frauds Page 4 C. Someone else’s debt The third type of contract which must be in writing is a promise to pay someone else’s debt. There is one exception to this rule: If a party promises to pay off another party’s debt in order to receive a benefit, such as an organization trying to get a tax break, this qualifies as a main purpose exception and the oral contract is enforceable under contract law. Consider the following scenario under the Statute of Frauds: Rachel is Catherine’s mother. In college, Catherine declared herself as independent and emancipated from her parents, but still maintained close ties with them. Catherine is now in her 30s and carries a large amount of debt from her student loans that she’s having difficulty paying. Rachel volunteers to help her out. Rachel realizes that if she helps Catherine pay, her other two daughters will ask for her financial assistance as well. She decides to help Catherine find other ways of paying off her debt. o Their oral contract is unenforceable. Rachel does not have to pay off Catherine’s debt because their contract was not in writing and the Statute of Frauds pertains to these types of promises. Rachel knows that if Catherine’s debts are paid off, she will finally move to Hollywood to pursue her acting career. If she is successful, Rachel might get famous riding Catherine’s coattails as her mother. She plans to use this new-found fame to publicize the novel she has been writing. She considers Catherine’s debt a small price to pay for all of the benefits she will receive by being a famous author, the mother of a famous daughter. One month, however, she forgets to pay the debt and Catherine becomes angry with her mother. Frustrated, Rachel decides not to pay at all. o Their oral contract is enforceable. Rachel is legally and contractually bound to pay Catherine’s debt. This is due to the main purpose exception to the Statute of Frauds. A promise to pay someone else’s debt for selfish reasons is legally binding, whether it was an oral or written contract. D. Debts of deceased The fourth type of contract under the Statute of Frauds’ domain pertains to paying the debts of the deceased. If an administrator of an estate is going to pay the debts of the deceased personally, a written document is required. Consider the following scenario under the Statute of Frauds: Janet and Simon are brother and sister in their elderly years. Simon has tremendous debt, so Janet frequently helps him out, just like she used to do when they were kids. Janet says to Simon, “I promise I’ll help you pay off your debts. I don’t want to see you stressing out because Chapter 20 Statute of Frauds Page 5 of all these financial issues, so I’ll just pay out of my pocket.” The next month, Simon has a heart attack in his sleep and dies, leaving Janet as the administrator of his estate. Now, credit companies are coming after her for her own personal money to pay off Simon’s debt. Their oral contract is unenforceable. Simon and Janet did not have a valid contract under the Statute of Frauds, which requires that promises by an administrator of the estate who will be personally paying for the deceased’s debts be made on paper. Therefore, Janet cannot personally be held accountable for her brother’s debts. E. Dowry Dowry is the fifth division of the Statute of Frauds. Any property that will change hands as part of an agreement to get married is considered dowry and an oral contract is not enforceable. Consider the following scenario under the Statute of Frauds: Mark is madly in love with Eileen and cannot wait for their wedding day. Eileen’s parents are so excited to give away their only daughter to the man of her dreams that they forget to make a written contract pertaining to her dowry--a house in the countryside and a goat. When Eileen and Mark get divorced two years later, Mark wants his lawyer to fight for custody of the countryside house and their goat, Jacob. Mark believes these things to be his property, given to him as a dowry gift from Eileen’s parents when they got married. Their oral contract is unenforceable. According to the Statute of Frauds, all property that changes hands as part of a marriage agreement must be in writing. F. Goods The final element of the Statute of Frauds pertains to goods worth $500 or more. Contracts for goods of $500 or more must be in writing, according to the Uniform Commercial Code, under the Statute of Frauds. However, there are many exceptions to this rule. For example, oral contracts for specially manufactured goods that cannot be resold are binding no matter the total cost. Also, if a seller-written confirmation is exchanged between the parties, which verifies the oral goods contract and is not objected to by either party within ten days, both parties are bound to the contract, despite the monetary amount of the goods. In addition, it is allowable for some oral contracts for goods to be partially fulfilled. If an oral contract is for sixty units of a good which are priced $10 each, the total cost of the goods is $600. Though this is unenforceable under the Statute of Frauds because the total is over $500, if $200 of the transaction is exchanged, twenty goods of the sixty dictated in the contract, must also be exchanged, or vice versa. This is because the contract is being partially performed. However, if the contract was for one large good which cost $600 individually and there was a payment of $200, it is not possible to only exchange part of the good. Therefore, the good must Chapter 20 Statute of Frauds Page 6 be exchanged and the party making the payment must make the payment in full. This type of full performance is enforceable in court, even if there is no written contract. See the examples below for a better understanding of the application of full and partial performance. Consider the following under the Statute of Frauds: Susanne has sold lilacs from her garden to Ryan, the local florist, for over ten years and they have a healthy relationship. So, when Ryan orders 400 lilacs from Susanne, she starts feeding her lilac plants plenty of fertilizer, preparing for Ryan’s order. Susanne decides to give Ryan a deal--the low price of $1 per lilac, an order total of $400. Later that week, Ryan calls apologetically to tell Susanne that he does not need the lilacs anymore and cancels his order. Susanne claims he is breaching the terms of their contract. o Their oral contract is enforceable. Because the price of the goods is less than $500, the Statute of Frauds does not cover this goods contract and an oral contract is enough to make a binding contract. Susanne charges Ryan $2 per lilac, an order total of $800. Later that week, Ryan calls to cancel his order. Susanne claims he is breaching the terms of their contract. o Their oral contract is unenforceable. The Statute of Frauds dictates that contracts pertaining to goods which total more than $500 must be in writing. Ryan does not have to pay for the lilacs. Susanne charges Ryan $2 per lilac, an order total of $800, which he will pay when he receives the order in full. Later that week, Susanne drops off $400 worth of lilacs. The next week, right before Susanne is about to drop off the second batch of lilacs, Ryan calls to tell her not to bring them over--he actually cannot afford to pay for any of the lilacs. o Their oral contract is enforceable for up to $400. Because the order total is $800, the Statute of Frauds requires a written contract for the goods. However, because only $400 of the contract was actually exchanged, this falls under the partial performance exception. Four hundred dollars is less than the minimum of $500, so that much of the contract was legally binding and Ryan must pay for $400 worth of lilacs. Ryan and Susanne decide that a more efficient exchange for both of them would be for Susanne to just sell her lilac bush to Ryan for $800. He gives her $200 and tells her he cannot afford to pay any more money. o Their contract is enforceable for the full amount. Though this is an order over $500 and should have a written contract under the Statute of Frauds, partial payment on a contract for one item, no matter the total, enforces the contract for the entire purchase. Ryan requests that Susanne dip the lilacs in a pink dye for his special order. The order total is $800. Susanne begins working on the order. o Their oral contract is enforceable. An exception to the Statute of Frauds rule about goods is that the contract is valid if it pertains to goods which cannot be resold Chapter 20 Statute of Frauds Page 7 because they were manufactured specifically for the buyer. If the special item cannot be readily resold and the seller has already begun work on the order, the good is covered by this exception to the Statute of Frauds. Ryan brings Susanne to court because he’s not getting his order as he correctly ordered it. In court, under oath, Susanne admits to their oral contract. o Their oral contract is enforceable. Court admissions are an exception to any rules about goods that fall under the Statute of Frauds. If the party in question admits in court that there was an oral contract, then the contract is valid. Susanne tells Ryan his order total will be $800. She goes home that night after the oral contract is made and writes a confirmation note for her own records. She photocopies it and sends it in the mail to Ryan. Ryan receives it and forgets about it, but then sends a letter objecting to the order and the contract two weeks later. o Their oral contract is enforceable. Because both parties involved are merchants, under the Statute of Frauds, a written confirmation sent by one party makes an oral contact valid, no matter the total cost. If Ryan had objected within ten days, the contract would have been void. Chapter 20 Statute of Frauds Page 8 Here is an easy way to remember the Statute of Frauds: Five hundred marriages will die from real estate debt in the next one year if they don’t sign a contract. Five hundred- the goods rule about $500 or more Marriages- Dowry Die- Personal payment for the deceased Real estate- Real estate contracts Debt- Pay someone else’s debts One Year- Contracts that will take longer than a year Sign a Contract- All of the above types of contracts must be written! These types of oral contracts are unenforceable. Though this is not an incredibly optimistic way to remember which types of contracts fall under the Statute of Frauds, it would be a pretty pessimistic day if an oral contract was not enforceable! Do not forget the very important exceptions to each of the rules, as well. Chapter 20 Statute of Frauds Page 9 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HPYz 2IzIii0&feature=related Technically, Charlie Brown would not even need a written contract to make his contract with Lucy enforceable. Their agreement does not fall under the Statute of Frauds and, therefore, an oral contract is acceptable. G. Who must sign the contract under the Statute of Frauds? Contracts do not necessarily have to be signed by both parties, though it is prudent for that to happen. The Statute of Frauds only requires written contacts to have the signature of the party to be charged, or the person who claimed that there was no deal. Without this signature, it is likely that the contract will be considered unenforceable. Some real estate documents (deeds, mortgages, and easements) require the signature of the party selling or giving up the real estate rights. II. Parol Evidence Rule Though oral contracts are generally binding, these few exceptions dictated by the Statute of Frauds can be hard to keep straight. For this reason, as a rule of thumb, written contracts are generally more reliable and safe than oral ones. Written contracts are more likely than oral contracts to stand up in court in the case of a disagreement between parties. However, even written contracts can be problematic. Sometimes the contract itself is not enough to prove its validity in court. The Parol Evidence Rule states that parties cannot normally provide additional evidence of an agreement that either supplements or contradicts the current written contract. This rule protects the integrity of the written contract--its terms cannot easily be breached or weakened by new agreements. New evidence complicates the court hearing and the contract’s original terms. There are four exceptions to the Parol Evidence Rule; four situations where new evidence can be introduced to make a case on a contract. The first exception is when a contract is short, or partially-integrated, and much shorter than normal. Such a contract may contain only one or two lines because the terms of the contract are fairly standard and well understood. However, additional information may need to be added to the contract for clarity’s sake and to make it more specific. This rule is not applicable if the additional information directly contradicts the terms of the original contract. Consider the Chapter 20 Statute of Frauds Page 10 following: Julie owes Emilie $100. The two orally agree that Julie will sell Emilie textbooks for $300 and the $100 previously mentioned will be credited against the $300 price. They sign a written agreement, but it does not mention the $100 of debt, redefined as a credit. Thus, the written agreement is partially-integrated making the oral agreement from the $100 credit admissible evidence to enhance the written agreement. Even if a contract is not partially-integrated, it may still be vague or unclear. If additional clauses are added to the contract to explain unclear provisions, these are also exceptions to the Parol Evidence Rule. For example, James got distracted when he was typing up his real-estate contract for his tenant. Under lawn-keeping, he simply wrote, “Must look good.” When his tenant Michelle was confused as to the terms, James wrote on the contract that the lawn must be mowed every other week, leaves must be raked every week in the fall, and the lawn must be watered every other day during summer’s hottest months, July and August. This would be acceptable under the Parol Evidence Rule because it does not change the terms of the contract, but rather just explains it in further detail. The third situation in which evidence is allowed in the court is when there is a clerical error, mistake, or a case of fraud. For example, a lease for an apartment may ask for $40 per month instead of $400 per month. The new evidence would correct the issue. The fourth exception is when an agreement is made after the written contract. The agreement will be valid evidence as long as it can be proven that the agreement was made after the original written contract. This allows for situations where both parties are in favor of the new terms of agreement over the old ones. They should not be forced to follow the original written contract, but should instead be allowed to introduce evidence of their new agreement. For example, Kelly bought a wide-screen television from Wal-Mart. The written contract made on May 2nd stated that the parties agreed the television would be delivered to Kelly at Wal-Mart’s expense on May 15th. On May 10th, Kelly contacted Wal-Mart stating she would rather pick up the television from the store. Wal-Mart would be in favor of this as it would no longer incur delivery charges. In order to be admissible, it must be proven that these new terms were made and agreed upon after the original written contract date of May 2nd. The first three types of evidence are typically found on the original document as clauses handwritten in the margins or in the footnotes, and initialed or signed by both parties. Chapter 20 Statute of Frauds Page 11 As can be seen in the Yocca v. Pittsburgh Steelers Sports, Inc. case below, once a contract is written, the terms included are the enforceable terms. Any previous agreements do not matter; the written contract is the final contract with which the parties must comply. Yocca v. Pittsburgh Steelers Sports, Inc. 2004 578 Pa. 479, 854 A.2d 425. Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, In October 1998, Pittsburgh Steelers Sports, Inc. and others (the Steelers) advertised a new stadium that was to be built. The Steelers sent out brochures to Ronald Yocca and others to give them the chance to buy stadium builder licenses (SBLs). SBLs give the holders the right to purchase season tickets each year. The price varies by the seats’ location. In these initial brochures, the Steelers included a diagram in which Yocca selected his preferred seat location in his application. The Steelers then sent Yocca a confirmation letter with his seat location and a more detailed diagram. This diagram differed from the initial one. Also included in this confirmation package were documents defining the terms of the SBL and contained the phrase “This Agreement contains the entire agreement of the parties”. Yocca signed the terms and sent them back to the Steelers. When Yocca showed up to the stadium at game time, his seats were not where he expected. Yocca and other SBLs filed suit against the Steelers claiming a breach of contract. When the court of Pennsylvania ordered a dismissal of the complaint, the plaintiffs appealed to the state intermediate appellate court, which reversed the order. The defendants then appealed to the state supreme court. Justice Nigro When the parties put their agreements in writing, the law states that this is the best and only evidence of their agreement. All previous negotiations are merged in and superseded by the following written agreement. Its terms and agreements cannot be changed due to parol evidence. Therefore, for the parol evidence rule to apply there must be a writing that represents the entire contract between the parties. To determine if the parties’ contract is complete, there must not be any uncertainty as to the object or extent of the parties’ engagement. An integration clause, which is a provision that says that all the terms are in the written agreement, signifies that the agreement is just what was written, and only what was in the agreement. Once it is determined that the entire contract is in the written agreement, the parol evidence rule now applies. Any previous oral or written agreements involving the same subject are now inadmissible. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court reversed the decision. The state Supreme Court held that the SBL documents which were signed formed the entire contract. Under the parol evidence rule, the contract is not supplemented by previous negotiations or agreements. Even though the plaintiffs based their claim that the brochure stated such initial terms, the court held that the brochure was not part of the contract. The complaint was properly dismissed. Chapter 20 Statute of Frauds Page 12 Vocabulary Easement: A real estate contract in which one party gives another party the permanent right to use their property. Must be in writing under the Statute of Frauds. Long term leases: Real estate contracts pertaining to a period of one year or more. Required to be in writing by the Statute of Frauds. Main purpose exception: Oral contracts promising to pay off someone else’s debt are enforceable if the promise was made for a selfish reason, such as an individual or company aiming to benefit from paying the debt. This is an exception to the Statute of Frauds. Partially-integrated contract: Short and brief contract which contains only a few lines because the terms of the contract are fairly standard and well understood. Parol Evidence Rule: Rule that states that neither party can introduce additional evidence of an agreement that either supplements or contradicts the current written contract. There are four main exceptions. Party to be charged: The party who claims a written contract is voidable and brings it to court. Without this person’s signature, the written contract is likely to be unenforceable. Statute of Frauds: The requirement that certain types of contracts must be in writing to be enforceable. While oral contracts are normally valid, the Statute of Frauds outlines which contracts must be in writing. It applies to six different types of contracts. Chapter 20 Statute of Frauds Page 13