Statute of Frauds

advertisement

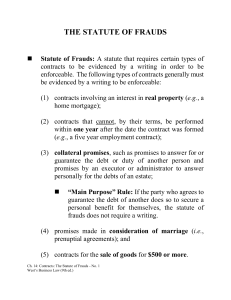

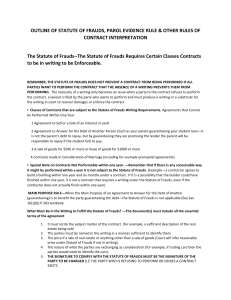

Commercial Law (Mgmt 348) Professor Charles H. Smith The Statute of Frauds-Writing Requirement (Chapter 15) Spring 2009 “Putting It In Writing” Always a good idea – this chapter deals with two issues that pertain to doing just that −Statute of frauds (Civil Code § 1624) – requires certain contracts to be in writing. −Parol evidence rule (C.C.P. § 1856) – written contract is final statement of parties’ agreement. Introduction to the Statute of Frauds Actually not a statute but an old common law rule though California and other states have codified it. Statute of frauds requires certain contracts to be in writing; examples include agreement that cannot be performed within a year, promise to answer for debt of another, and real estate contract. Statute of frauds simply reflects policy decision that some contracts need to be in writing. Statute of Frauds – Contract Cannot be Performed Within One Year This means that, by its terms, it is impossible to perform the contract within a year (Civil Code § 1624(a)(1)). Therefore, contract not covered by statute of frauds if performance within a year is merely improbable or not desired. Case study – Sawyer v. Mills (pages 305-06). Statute of Frauds – Promise to Pay Another’s Debt “Promise to answer for the debt of another” (Civil Code § 1624(a)(2)). Examples include − Co-signing loan. − Personal guarantee for company obligation. Case study – Case Problem 15-10 (pages 319-20). Statute of Frauds – Transactions Involving Real Estate Civil Code § 1624(a)(3) provides these situations − Lease for more than one year. − Sale of real estate; can be any interest, not just 100%. Case study – Case Problem 15-6 (pages 318-19). Exceptions to Application of Statute of Frauds Part performance; case study – School-Link Technologies, Inc. v. Applied Resources, Inc. (pages 30910). Admission – must occur in court proceedings; e.g., during deposition or trial testimony, or in papers filed with court. Promissory estoppel – detrimental reliance on oral contract; however, must be reasonable; case study – Case Problem 15-4 (page 318). What is a “Writing” for Purposes of Statute of Frauds? Evidence Code § 240 provides broad definition of “writing.” Civil Code § 1624(a) requires the writing to be “subscribed [signed] by the party to be charged” – how to “subscribe” (or sign) electronic contract? Introduction to the Parol Evidence Rule Old common law rule – writing intended as final expression of parties’ agreement cannot be contradicted by evidence of prior agreement or contemporaneous oral agreement; therefore, writing should correctly and fully reflect parties’ agreement. Policy is to uphold written contract that is intended to be final statement of parties’ agreement; this intent can be shown by testimony or “integration” clause. Many exceptions to parol evidence rule which will be described in subsequent slides. Parol Evidence Rule – Case Studies Yocca v. Pittsburgh Steelers Sports, Inc. (pages 313-15). Case Problem 15-8 (page 319). Exception - Course of Dealing or Usage of Trade Words often have special meaning different from ordinary meaning in certain industries or settings; thus, evidence can be admitted to provide definitions/context. Example – “baker’s dozen” means 13, not 12; general phrase like “time is of the essence” may have specific meaning given history of parties’ history. Student examples. Exception – Validity of Contract in Dispute Is mutual assent being questioned? Can include situations where someone alleges the contract is voidable such as duress or undue influence. Also can include situations where someone alleges the contract is void due to an illegal purpose. Exception – Ambiguity Parol evidence rule exception about “ambiguity” of contract terms can be very wide-ranging since “[t]he test of admissibility of extrinsic evidence to explain the meaning of a written instrument is not whether it appears to the court to be plain and unambiguous on its face, but whether the offered evidence is relevant to prove a meaning to which the language of the instrument is reasonably susceptible . . . A rule that would limit the determination of the meaning of a written instrument to its four-corners merely because it seems to the court to be clear and unambiguous, would either deny the relevance of the intention of the parties or presuppose a degree of verbal precision and stability our language has not attained” (Pacific Gas & Electric Co. v. G.W. Thomas Drayage, 69 Cal.2d 33, 38 (1968)). Caveat – do not depend on being able to testify as to any “ambiguities.” Cutting Edge Legal Issue Case study – “Prenuptial Agreements and Advice of Counsel” (pages 312-13). Discuss with small groups – where do you stand (and why)?