Vaccines

advertisement

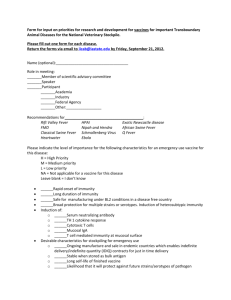

Vaccines Artificially Acquired Active Immunity Mike Clark, M.D. • Vaccines (organism dead or attenuated) – Spare us the symptoms of the primary response – Provide antigenic determinants that are immunogenic and reactive – Older vaccines target only one type of helper T cell (TH 2 rather than TH 1) , so fail to fully establish cellular immunological memory – TH2 activates the B-cell system whereas TH 1 activates the T-cell system – Naked DNA vaccines and oral vaccines avoid this problem – Sometimes can become to something in vaccine – like egg albumin found in the influenza vaccines (adjuvants) Vaccines • A vaccine is a biological preparation that improves immunity to a particular disease. A vaccine typically contains an agent that resembles a disease-causing microorganism, and is often made from weakened or killed forms of the microbe or its toxins. The agent stimulates the body's immune system to recognize the agent as foreign, destroy it, and "recognize" it, so that the immune system can more easily recognize and destroy any of these microorganisms that it later encounters. • Vaccines can be prophylactic (e.g. to prevent or ameliorate the effects of a future infection by any natural or "wild" pathogen), or therapeutic (e.g. vaccines against cancer are also being investigated). • The term vaccine derives from Edward Jenner‘s 1796 use of the term cow pox (Latin variolæ vaccinæ, adapted from the Latin vaccīn-us, from vacca cow), which, when administered to humans, provided them protection against smallpox. History • Sometime during the 1770s Edward Jenner heard a milkmaid boast that she would never have the often-fatal or disfiguring disease smallpox, because she had already had cowpox, which has a very mild effect in humans. In 1796, Jenner took pus from the hand of a milkmaid with cowpox, inoculated an 8-year-old boy with it, and six weeks later variolated the boy's arm with smallpox, afterwards observing that the boy did not catch smallpox. Further experimentation demonstrated the efficacy of the procedure on an infant. • Louis Pasteur generalized Jenner's idea by developing what he called a rabies vaccine (now termed an antitoxin), and in the 19th century vaccines were considered a matter of national prestige, and compulsory vaccination laws were passed • The 20th century saw the introduction of several successful vaccines, including those against diphtheria, measles, mumps, and rubella. Major achievements included the development of the polio vaccine in the 1950s and the eradication of smallpox during the 1960s and 1970s. • Problem: As vaccines became more common, many people began taking them for granted. • However, vaccines still remain elusive for many important diseases, including malaria and HIV Types of Vaccines (Dead Organism) Some vaccines contain killed, but previously virulent, micro-organisms that have been destroyed with chemicals or heat. Examples are the influenza vaccine, cholera vaccine, bubonic plague vaccine, polio vaccine, hepatitis A vaccine, and rabies vaccine. Types of Vaccines (Attenuated) • Some vaccines contain live, attenuated microorganisms. Many of these are live viruses that have been cultivated under conditions that disable their virulent properties, or which use closely-related but less dangerous organisms to produce a broad immune response, however some are bacterial in nature. • They typically provoke more durable immunological responses and are the preferred type for healthy adults. • Examples include the viral diseases yellow fever, measles, rubella, and mumps and the bacterial disease typhoid. • The live Mycobacterium tuberculosis vaccine is not made of a contagious strain, but contains a virulently modified strain called "BCG" used to elicit immunogenicity to the vaccine. (Bacillus Calmette-Guérin – named after developers). Vaccines (Toxoid) • Toxoid vaccines are made from inactivated toxic compounds that cause illness rather than the micro-organism. Examples of toxoidbased vaccines include tetanus and diphtheria. Toxoid vaccines are known for their efficacy. Not all toxoids are for microorganisms; for example, Crotalus atrox toxoid is used to vaccinate dogs against rattlesnake bites. Vaccines ( Protein- Subunit) Epitope • Rather than introducing an inactivated or attenuated micro-organism to an immune system (which would constitute a "whole-agent" vaccine), a fragment of it can create an immune response. Examples include the subunit vaccine against Hepatitis B virus that is composed of only the surface proteins of the virus (previously extracted from the blood serum of chronically infected patients, but now produced by recombination of the viral genes into yeast), the virus-like particle (VLP) vaccine against human papillomavirus (HPV) that is composed of the viral major capsid protein, and the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase subunits of the influenza virus. Vaccines (Conjugate) “making a complete antigen out of a partial one” Conjugate – certain bacteria have polysaccharide outer coats that are poorly immunogenic. By linking these outer coats to proteins (e.g. toxins), the immune system can be led to recognize the polysaccharide as if it were a protein antigen. This approach is used in the Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine. Newly Developed Vaccines • Recombinant Vector – by combining the physiology of one micro-organism and the DNA of the other, immunity can be created against diseases that have complex infection processes • Naked DNA vaccination – in recent years a new type of vaccine called DNA vaccination, created from an infectious agent's DNA, has been developed. It works by insertion (and expression, triggering immune system recognition) of viral or bacterial DNA into human or animal cells. Some cells of the immune system that recognize the proteins expressed will mount an attack against these proteins and cells expressing them. Because these cells live for a very long time, if the pathogen that normally expresses these proteins is encountered at a later time, they will be attacked instantly by the immune system. One advantage of DNA vaccines is that they are very easy to produce and store. As of 2006, DNA vaccination is still experimental. Adjuvants • An adjuvant is an agent that may stimulate the immune system and increase the response to a vaccine, without having any specific antigenic effect in itself. The word “adjuvant” comes from the Latin word adjuvare, meaning to help or aid. "An immunologic adjuvant is defined as any substance that acts to accelerate, prolong, or enhance antigen-specific immune responses when used in combination with specific vaccine antigens • There are many known adjuvants in widespread use, including oils, aluminium salts, and virosomes, although precisely how they work is still not entirely understood. Aluminium salts • There are many adjuvants, some of which are inorganic (such as alum), that also carry the potential to augment immunogenicity. Two common salts include aluminium phosphate and aluminium hydroxide. These are the most common adjuvants in human vaccines Booster Shots • Unfortunately, one shot is not enough to protect a person from the disease you are vaccinating against. Whenever a person is vaccinated the person's immune system will activate a certain number of cells called B-cells. These B-cells will multiply and some of them will produce antibodies. Others of these multiplying B-cells will become memory cells. Memory B-cells can last for decades in our bodies and are able to make antibody whenever the microorganism you are vaccinated against infects your body. This first vaccine doesn't get enough of these B-cells activated. Booster shots activate more B-cells. When more B-cells are activated more antibodies are made. More antibody results in better protection from the microorganisms you are vaccinated against. In other words you get a higher (stronger) immune response • The timing of a booster shot is also important. If you give it too soon then the antibodies present in the blood from the first shot will eliminate the material in the vaccine before you can activate more of those B-cells. Therefore, a waiting period between shots is required to allow time for Naked DNA Vaccines • Oftentimes injected with a gene gun – allows stimulation of both TH1 and TH2 lymphocytes • A gene gun or a biolistic particle delivery system, originally designed for plant transformation, is a device for injecting cells with genetic information Edible Vaccines Oral vaccines produced in transgenic plants • Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is probably the single most important cause of persistent viremia in humans. The disease is characterized by acute and chronic hepatitis, which can also initiate hepatocellular carcinoma. The prevalence of this disease in developing countries justified initial efforts to express HBV candidate vaccines in plants. • Currently, two forms of HBV vaccines are available, both of which are injectable and expensive: one purified from the serum of infected individuals and the other a recombinant antigen expressed and purified from yeast. We have transformed plants with the gene encoding the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg); this is the same antigen used in the commercial yeast-derived vaccine. An antigenic spherical particle was recovered from these plants which is analogous to the recombinant hepatitis surface antigen (rHBsAg) derived from yeast. Parenteral immunization of mice with the plant-derived material has demonstrated that it retains both B- and T-cell epitopes, as compared to the commercial vaccine. To build these edible vaccines, researchers take cells from plants and coax them to multiply like bacteria cultures. Then they insert the desired gene, and "plant" the cells in a growing medium, where they sprout new plants—and hopefully the antigen gene is expressed in the fruit or vegetable. ADVANTAGES 1.Edible means of administration and gives excellent safety compared to injection. 2.It generates systemic and mucosal immunity. This is essential to avoid respiratory and digestive tracts infection. 3.Heat stability. Stable at room temperature. No need of refrigeration. 4.Mass production is possible. 5.Reduction in production costs. 6.Plants can be easily reproduced as compared to animals, used as a system for vaccines production. 7. Stimulates both T cell and B cell activity Hepatitis B Vaccine • Vaccinate persons with any of the following indications and any person seeking protection from hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. • Behavioral: Sexually active persons who are not in a long-term, mutually monogamous relationship (e.g., persons with more than one sex partner during the previous 6 months); persons seeking evaluation or treatment for a sexually transmitted disease (STD); current or recent injection-drug users; and men who have sex with men. • Occupational: Health-care personnel and public-safety workers who are exposed to blood or other potentially infectious body fluids. • Medical: Persons with end-stage renal disease, including patients receiving hemodialysis; persons with HIV infection; and persons with chronic liver disease. • Other: Household contacts and sex partners of persons with chronic HBV infection; clients and staff members of institutions for persons with developmental disabilities; and international travelers to countries with high or intermediate prevalence of chronic HBV infection Dosing of Hepatis B Vaccine • Administer or complete a 3-dose series of hepatitis B vaccine to those persons not previously vaccinated. The second dose should be administered 1 month after the first dose; the third dose should be administered at least 2 months after the second dose (and at least 4 months after the first dose). If the combined hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccine (Twinrix) is used, administer 3 doses at 0, 1, and 6 months; alternatively, a 4-dose schedule, administered on days 0, 7, and 21–30 followed by a booster dose at month 12 may be used. • Adult patients receiving hemodialysis or with other immunocompromising conditions should receive 1 dose of 40 μg/mL Duration of Protection for Hepatitis B Vaccine • Although initially it was thought that the hepatitis B vaccine did not provide indefinite protection, this is no longer considered the case. Previous reports had suggested vaccination would provide effective cover of between five and seven years, but subsequently it has been appreciated that long-term immunity derives from immunological memory which outlasts the loss of antibody levels and hence subsequent testing and administration of booster doses is not required in successfully vaccinated immunocompetent individuals. Hence with the passage of time and longer experience, protection has been shown for at least 25 years in those who showed an adequate initial response to the primary course of vaccinations, and UK guidelines now suggest that for initial responders who require ongoing protection, such as for healthcare workers, only a single booster is advocated at 5 years.