Content Area 2:

advertisement

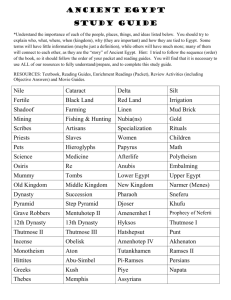

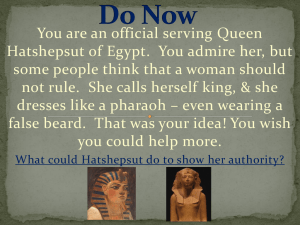

Content Area 2: Ancient Mediterranean 3500-300 CE Mesopotamia and Egypt (15 works) 12. White Temple and its ziggurat. Uruk (modern Warka, Iraq). Sumerian. c. 3500–3000 B.C.E. Mud brick. 14. Statues of votive figures, from the Square Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar, Iraq). Sumerian. c. 2700 B.C.E. Gypsum inlaid with shell and black limestone. The Standard of Ur was an Ancient Sumerian box that contained a “Peace” side (left) and a “War” side (below) Sumerian 16. Standard of Ur from the Royal Tombs at Ur (modern Tell elMuqayyar, Iraq). Sumerian. c. 2600– 2400 B.C.E. Wood inlaid with shell, lapis lazuli, and red limestone. Sumerian War side of the Standard of Ur, Royal Cemetery, Iraq, c.2600BCE. Wood inlaid with shell, lapis lazuli, and red limestone, approx 8” x 1’ 7”. Sumerian Peace side of the Standard of Ur. Babylonian: Stele with law code of Hammurabi, Iran, c.1780BCE. Basalt, 7’4”H. being commissioned by sun god Shamash to inscribe these 282 laws in 400 lines of text; united Mesopotamia under his rule. “the king who made the four quarters of the earth obedient” The top portion, shown here, depicts Hammurabi with Shamash, the sun god. Shamash is presenting to Hammurabi a staff and ring, which symbolize the power to administer the law. Hammurabi, with the help of his impressive Babylonian army, conquered his rivals and established a unified Mesopotamia. He proved to be as great an administrator as he was a general. The code of Hammurabi contained 282 laws, written by scribes on 12 tablets. Unlike earlier laws, it was written in Akkadian, the daily language of Babylon, and could therefore be read by any literate person in the city. 19. The Code of Hammurabi. Babylon (modern Iran). Susian. c. 1792–1750 B.C.E. Basalt. Hammurabi said that with this code of law he intended “to cause justice to prevail in the land and to destroy the wicked and the evil, that the strong might not oppress the weak nor the weak the strong.” 25. Lamassu from the citadel of Sargon II, Dur Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad, Iraq). Neo-Assyrian. c. 720–705 B.C.E. Alabaster. PERSIA and the city of PERSEPOLIS 521-465 BCE (present day Iran) Royal Audience Hall (apadana, 60’H, 200’SQ.) 30. Audience Hall (apadana) of Darius and Xerxes. Persepolis, Iran. Persian. c. 520–465 B.C.E. Limestone. 13. The Palette of King Narmer Hierakonpolis, Egypt, Predynastic 3000-2920 BCE, greywacke, 2’1”H Predynastic Egypt The Palette of King Narmer is one earliest historical artworks preserved. It was, at one time, regarded as commemorating the foundation of the first of Egypt’s thirty-one dynasties around 2920 BC (the last ended in 332 BC) This image records the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt into the “Kingdom of Two Lands” . Egyptians prepared eye makeup on tablets such as this for protecting their eyes against irritation and the sun’s glare. This palette is not only important because of its historical content, but it also serves as a blueprint of the formula for figure representation that characterized Egyptian art for three thousand years. The back of the palette depicts the king wearing the bowlingpin-shaped crown of Upper Egypt accompanied by an official who carries his sandals. The king is in the process of slaying his enemy and is significant in the pictorial formula for signifying the inevitable triumph of the Egyptian god-kings. Used to hold the eye makeup The falcon is a symbol of Horus, the kings protector. Below the ground-line of the king are two of his fallen enemies. Above the king are the two heads of Hathor a goddess of favorable dispose to Narmer and shown as the cow with a woman’s face. Between these two faces is the hieroglyph of Narmer’s name with a frame representing the Royal Palace. Symbolic of the unification The front of the palette depicts the king wearing the red cobra crown of Lower Egypt. The bodies of the dead are seen from above, as each body is depicted with it’s head severed and neatly placed between its legs. 15. Seated Scribe Saqqara, Egypt, Dynasty IV Ca 2620-2500 BCE. Painted limestone. The Scribe is a high court official- most scribes were sons of pharaohs. (Alert expression in face, individualized torsoflabby and middle-aged) Old kingdom also invented the portrait bust- whether it was an abbreviated statue or had some greater significance is unknown Notice the realism depicted in this sculpture, when compared to that of the Pharaohs. His depiction in this manner is a result of his lower hierarchy in Egyptian society than that of a Pharaoh. It has been said that it could take up to 10 years for a scribe to learn the language of hieroglyphics that contained nearly 700 characters. 18. King Menkaura and queen. Old Kingdom. Gizeh, Egypt Dynasty IV, ca 2490-2472 BCE Graywacke, approx. 4’6 ½”H. Standing (common pose), both have left foot forward, yet their bodies are static . The stone from which they were created still is still visible, maintaining the block form. These figures were meant to house the ka . This was the stereotypical pose that symbolized marriage. Notice how the figures are idealized and emotionless. The artists depiction of these two people is indicative of the formula for depicting royalty in Egyptian Art. Burial Chamber is in the center of the pyramid rather than underneath 17. The Old Kingdom: Great Pyramids Gizeh, Egypt, Dynasty IV: Menkaure, Khafre, Khufu Originally covered in smooth stone that would be reflective in the sun. (Almost blinding to the eyes.) Fourth Dynasty pharaohs considered themselves to be the sons of the sun God Re and his incarnation on Earth. Egyptians always buried their dead on the west side of the Nile, in a necropolis, where the sun sets. The largest of the pyramids, Khufu, is about 450 feet tall and has an area of almost 13 acres. It contains almost 2.3 million blocks of stone, each weighing about 2.5 tons. The Great Pyramid at Gizeh is the oldest and only still existing of the seven wonders of the ancient world The Great Sphinx The Sphinx, a lion with a human head, commemorated the pharaoh and served as an immovable, eternal silent guardian of his tomb. This guardian stood watch at the entrances to the palaces of their kings. It gives visitors coming from the east the illusion that it rests on a great pedestal. The face of the Sphinx is thought to be an image of the pharaoh Khafre, Khufu’s second son. 17. Great Sphinx, Gizeh, Egypt, Dynasty IV ca. 2520-2494BCE. 65’H 20. Temple of Amun-Re and Hypostyle Hall. Karnak, near Luxor, Egypt. New Kingdom, 18th and 19th Dynasties. Temple: c. 1550 B.C.E.; hall: c. 1250 B.C.E. Cut sandstone and mud brick. Temple of Amen-Re, Karnak, Egypt, Dynasty XIX Ca 1290-1224 BCE. This temple is mainly the product of the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaohs, but some of the Nineteenth Dynasty pharaohs contributed to it as well. Contributors include: Thutmose I and II, Hatshepsut, and Ramses II. This temple is a great example of the hypostyle hall. ( A roof supported by many columns and example of post and lintel construction). The central section of the roof is raised. This architectural feature is called a clerestory. The function of this was to allow light and air to filter into the interior. The columns were decorated with a series of sunken relief sculptures. The New Kingdom: 21. Queen Hatshepsut’s Mortuary Temple Built 1480 BC (New Kingdom) Deir elBahri, Egypt. The colonnaded terraces were originally covered with trees and plants. . Queen Hatshepsut became the Pharoah when her husband Thutmose II had died. The heir to the throne was to be given to his twelve year old son, but he was too young to rule. Hatshepsut then assumed the role of King, and became the first great female monarch whose name was recorded. Many of the portraits of Hatshepsut were destroyed at the order of Thutmose III (the son too young to rule), as he was resentful of her declaration of herself as pharaoh. Akhenaton’s god was unlike any other Egyptian God in that it was not depicted by animal or human form. Instead, Aton was depicted only as a sun disk emitting live-giving rays. Stylistic Changes during the Amarna Period included: Effeminate elongated body and skull with curving contours Long full- lipped face, heavylidded eyes, and a dreamy expression. The body of Akhenaton is oddly misshapen with weak arms, a narrow waist, protruding belly, wide hips, and fatty thighs. 22. Akhenaton, Nefertiti, and three daughters. New Kingdom (Amarna), 18th Dynasty. c. 1353–1335 B.C.E. Limestone. 23. Tutankhamun’s tomb, innermost coffin. New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty. c. 1323 B.C.E. Gold with inlay of enamel and semiprecious stones. 24. Last judgment of Hu-Nefer, from his tomb (page from the Book of the Dead). New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty. c. 1275 B.C.E. Painted papyrus scroll, 1’6’L. Hu-Nefer was the royal scribe to the pharaoh Seti I. This painting depicts the jackal-headed god, Anubis, leading Hu-Nefer down the hall of judgment. His soul has been favorably weighed and he is being brought by Horus to the presence of the greenfaced Osiris. Books of the Dead held spells, prayers and incantations to instruct the dead. This formula for imagery in Hu-Nefer’s tomb demonstrates a return to the Old Kingdom funerary illustrations.