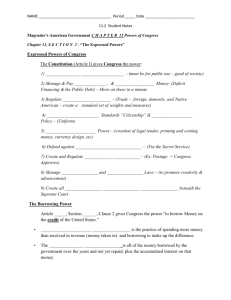

Constitutional Law I- Spring 2014

advertisement