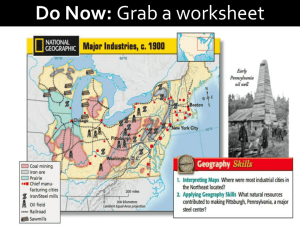

edwin drake

advertisement

EDWIN DRAKE Oil Drilling Dogged persistence led this man to drill -- and drill -- and drill, seeking oil deposits. His success launched an Oil Rush and brought the world a new energy source. Diplomat and Prospector Edwin Drake's first career was as a conductor on a brand new, sometimes dangerous conveyance: the railroad. In the late 1850s, New Haven speculator James Townsend hired Drake to investigate Titusville, Pennsylvania for oil deposits. He had seen a Yale chemistry professor's report that rock oil could be refined and employed for illumination, lubrication, and other uses. When Drake arrived, locals took to the agreeable man right away -- but laughed at his futile purpose. Small amounts of oil had seeped from the ground forever --but no one had figured out how to extract it. At last Drake found a reliable driller -- William A. "Uncle Billy" Smith, a blacksmith who forged his own tools and reported for work in late May. They built a derrick of pine wood and began drilling. Oil Workmen drilled all summer, six days a week, with the Sabbath Drake's inviolable day off. When water flooded the hole, Drake innovated a solution; he drove an iron pipe down to bedrock, then placed the drill inside the pipe to keep water out of the excavated shaft. The men drilled, and drilled, and drilled. Drake at last struck black gold, on August 28, 1859, nearly seventy feet down. New Industry, New Wealth By early fall, Pennsylvania's Oil Rush was on. Real estate prices skyrocketed and fortune-seekers arrived. Within a few years the oil refining business would attract John D. Rockefeller, a careful businessman who would use crafty tactics to build one of America's great industrial fortunes. Drake was not so lucky. Townsend's company fired him, and he lost his money on Wall Street. He never patented his drilling method. Years later, the oil barons who owed their wealth to Drake offered him financial support. And in 1873, Pennsylvania voted an annuity of $1,500 to the "crazy" man whose determination founded an industry. Drake died in 1880. WRIGHT BROTHERS Flight Enthusiasts Like a small but enthusiastic number of people in the U.S. and Europe, the Wrights believed human flight was possible. They broke the problem down into three elements: wing shape, power source, and control. Others had focused on the first two problems, but the Wrights knew from their bicycle experiences that control was key. From books in their father's library, the brothers schooled themselves on the mechanics of flight. Their "wing warping" mechanism, inspired by watching birds, was a revolutionary breakthrough. The Wrights' Flying Machine In 1899, they made their first flying machine -- a kind of kite made of wood, wire, and cloth. The small model succeeded on its test run and the brothers took the next step: human flight. Funding their experiments with the proceeds from their bicycle shop, and after much trial and error, Wilbur and Orville built their "Kitty Hawk Flyer," an instrument that had a lightweight, gas-powered engine and weighed 600 pounds. On December 17, 1903, lifting off from soft North Carolina sand dunes, the "Kitty Hawk" flew 120 feet, far enough to demonstrate that human flight was indeed possible. Almost a year before the test, the brothers had applied for a patent for their invention, which they finally secured in 1906. THOMAS EDISON The Science of Innovation The "Wizard of Menlo Park" brought the world electric light, recorded music, and the movies, among other things, and turned innovation into a science by inventing the research laboratory. The self-taught boy set up a mobile chemistry lab and printing press, and tinkered with telegraphy instruments, his lifelong habit of experimentation firmly in place. Over his career, Edison would successfully patent a record 1,093 inventions in the United States -- more than double the number of his closest competitor, George Westinghouse. Life-Changing Inventions Edison invented or refined devices that made a profound impact on how people lived. The most famous of his inventions was the incandescent light bulb (1878), which would revolutionize indoor lighting and forever separate light from fire. He also developed the phonograph (1877), the central power station (1881), the motion-picture studio (1892) and system for making and showing motion pictures (1893), and alkaline storage batteries (1901). Edison improved upon the original designs of the stock ticker, the telegraph, and Alexander Graham Bell's telephone. He was one of the first to explore X-rays, and in 1875, he announced his observation of "etheric force" -- radio waves -- although his claim would be rejected by the scientific community. The Business of Innovation Aside from being an inventor, Edison was also a successful manufacturer and businessman, marketing his inventions to the public. In 1876, the year of the American centennial, he opened his first full-scale industrial research laboratory in Menlo Park, New Jersey. It combined electrical and chemical laboratories with a machine shop. By 1880, his hand-picked staff was developing commercial electrical lighting components, and Edison opened a factory to produce them. Within seven years, there were 121 Edison central power stations across the country, each obliged to buy Edison components. For financial security, he sold a share of the business to banker J. P. Morgan, renaming his company the Edison General Electric Company. In 1892, following another merger, Edison would get out of the electricity business, and his loyal assistant, Samuel Insull, would head to Chicago to make his own name in power delivery. ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL The Telephone Alexander Graham Bell's invention of the telephone grew out of his research into ways to improve the telegraph. On April 6, 1875, Bell was granted the patent for the multiple telegraph, which sent two signals at the same time. for, transmitting vocal or other sounds telegraphically by causing electrical undulations, similar in form to the vibrations of the air accompanying the said vocal or other sounds. The Harmonic Telegraph In the 1870s the Bells moved to Canada and shortly after that, to Boston, Massachusetts, where Bell took a teaching position at the Pemberton Avenue School for the Deaf. He became increasingly interested in the possibility of transmitting speech over wires. Teaming up with a likeminded machinist, Thomas A. Watson, Bell worked for a year, and succeeded in transmitting the first telephone message on March 10, 1876. Bell took his "Harmonic Telegraph" to Philadelphia's Centennial Exhibition, where it astonished crowds. The partners were convinced their device could make money; they just weren't sure how. Phone Customers Doctors and pharmacists became early adopters of the technology, along with wealthy individuals, including Mark Twain. The famous writer installed a phone in his Hartford home even though he complained, "The human voice carries entirely too far as it is." In a mere four years, the American Bell Telephone Company deployed 60,000 telephones, providing service in every large American city. Polite young women found work at the switchboards, which were open from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. Telephone poles began to dot the landscape; the state of Vermont lost 45,000 pine trees in 1885 alone. By then, Bell had withdrawn from the business, leaving others to build the telephone industry. JOHN ROCKEFELLER John Rockefeller was an oil industrialist, investor and philanthropist. He was the founder of Standard Oil Company which was the first great trust and dominated the oil industry. Standard’s most potent weapon was underselling. It had become the richest, biggest, most feared business in the world. In today’s standards, John’s estimated value would be around 663 billion dollars, making him the richest man in history. His donations pioneered the development of medical research ANDREW CARNEGIE Andrew Carnegie, the son of a Scottish immigrant, quickly realized steel was the future after being impressed by the Bessemer process, The Carnegie Steel Company was created expanded and steel production from 332,111 to 2,663,412 tons per year. In 1901 J.P. Morgan purchased the Carnegie Company for $500,000,000 and established the U.S. Steel Corporation that was valued at $1.4 billion. Carnegie set up a trust fund "for the improvement of mankind." By 1919, Carnegie donated 350,000 to his causes. J.P. MORGAN J.P. Morgan started his own private banking company in 1871, which became J. P. Morgan & Co. His company was so powerful that even the U.S. government looked to the firm for help with the depression of 1895. Morgan dominated two industries in particular—he helped consolidate railroad industry in the East and formed the United States Steel Corporation in 1901. U.S. Steel became the world's largest steel manufacturer. At the time of his death, he was hailed as a master of finance and considered one of the country's leading businessmen. GEORGE PULLMAN George Pullman improved the comfort of rail travel at a time when it was America’s most important form of transportation. The traveling public, weary of cramped and uncomfortable sleeping accommodations, was so enthusiastic about the Pullman car that railroads made structural changes to bridges and platforms to accommodate its size. The first car was named Pioneer in 1863. CORNELIUS VANDERBILT Cornelius Vanderbilt built his wealth on shipping and railroads. He systematically took over New York by simply buying out his competitors or running them into the ground. Many paid him to not complete, earning the nickname The Commodore (highest rank in the navy). His estimated value in today’s standards would be around 147 billion dollars, making him the second richest man in American history. 95% of his inheritance went to his son William. His philanthropy went toward Vanderbilt University, named after him. GEORGE WESTINGHOUSE George Westinghouse was instrumental in increasing the safety of the American railroad system and encouraging the growth of the transportation industry. Westinghouse developed a fascination with steam engines. Riding the Rails His time in the army during the Civil War made him realize the importance of railroads to the national project of industrialization. Perceiving that increased safety on this new system of transportation was necessary for further development, Westinghouse invented and patented a compressed-air brake system in 1869 to replace the standard manual braking system, which was often faulty. He incorporated the Westinghouse Air Brake Company, the first of more than 60 companies he would form to market his and others' inventions. The 1893 Railroad Safety Appliance Act made air brakes compulsory on all American trains. In total Westinghouse made over 300 inventions that revolved around railroad travel, including a rotary steam engine, an effective means of righting cars that had been derailed, and a "frog," a switch that allowed trains to "hop" across rails at a junction. In 1883 he applied his knowledge of air brakes to the safe piping of natural gas, and within two years he obtained 38 patents for piping equipment. AC/DC Westinghouse also experimented with electricity and developed a transformer that could bring alternating current (AC) electricity down from high voltage to low -- thus enabling AC to travel long distances while still making it ready for use. He purchased Nikola Tesla's patents and hired him to improve his AC motor for use in Westinghouse's new power system. Westinghouse formed Westinghouse Electric in 1886 to compete with Thomas Edison's direct current (DC) system. Advocates of DC power set out to discredit AC power, charging that the use of AC power was a menace to human life and publicizing New York state's use of the Westinghouse AC generator as its official means of execution. In 1893, Westinghouse proved AC's safety when his company lit the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Soon after Westinghouse secured the rights to develop Niagara Falls, creating the first large system to supply electricity for multiple uses (railway, lighting, power) from one circuit. GEORGE EASTMAN Pupil and Inventor Invented in the 1830s, photography was a well-established professional occupation by the 1870s, but it was not a hobby for the masses. It required a knowledge of chemistry, mastery of cumbersome equipment, and an interest in laborious wet-plate processes. Eastman, in his early twenties, became the pupil of two Rochester, New York, amateur photographers, George Monroe and George Selden. He experimented in dry-plate photography, and developed a formula for gelatin-based paper film and a machine for coating dry plates. He went into business selling dry plates in April 1880, and soon resigned from his bookkeeping position at a local bank to focus on his fledgling company. Technical Advances In 1885, with camera inventor William Hall Walker, Eastman patented the Eastman-Walker Roll Holder, which allowed photographers to advance multiple exposures of paper film through a camera, rather than handle individual singleshot plates. The roll holder would define the basic technology of cameras until the introduction of digital photography. It also became the basis for the first mass-produced Kodak camera, initially known as the "roll holder breast camera," which retailed for $25 and started a photography craze. The term "Kodak" was coined by Eastman himself in 1887. In 1889, Eastman hired chemist Henry Reichenbach, who developed a transparent, flexible film which could be cut into strips and inserted into cameras. Thomas Edison would order the film to use in the motion-picture camera he was developing -- and it would soon become the centerpiece of the Eastman empire. Photography for the Masses During the 1890s, Eastman expanded his business, buying patents and investing in research and development. Faster films and smaller cameras meant photography could produce more spontaneous pictures -- "snapshots." In 1900, he introduced the "Brownie" camera, which sold for $1 and was a bullseye in the mass market. Eastman's insight was that his chemists could do the "photo finishing," but anyone could take pictures with a simple camera like the Brownie. Eastman had hit on a memorable slogan: You press the button, we do the rest." His business grew rapidly, helped by jingles and ads positioning the brand as an essential tool for preserving memories. A 1902 ad lectured, "A vacation without a Kodak is a vacation wasted." A blizzard of profits enabled Eastman to build a 50-room mansion in Rochester.