Lodge Corollary

advertisement

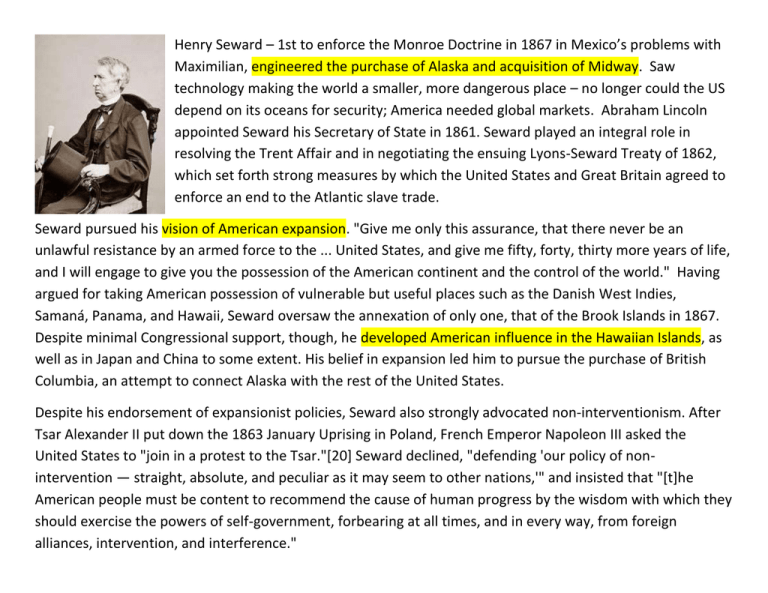

Henry Seward – 1st to enforce the Monroe Doctrine in 1867 in Mexico’s problems with Maximilian, engineered the purchase of Alaska and acquisition of Midway. Saw technology making the world a smaller, more dangerous place – no longer could the US depend on its oceans for security; America needed global markets. Abraham Lincoln appointed Seward his Secretary of State in 1861. Seward played an integral role in resolving the Trent Affair and in negotiating the ensuing Lyons-Seward Treaty of 1862, which set forth strong measures by which the United States and Great Britain agreed to enforce an end to the Atlantic slave trade. Seward pursued his vision of American expansion. "Give me only this assurance, that there never be an unlawful resistance by an armed force to the ... United States, and give me fifty, forty, thirty more years of life, and I will engage to give you the possession of the American continent and the control of the world." Having argued for taking American possession of vulnerable but useful places such as the Danish West Indies, Samaná, Panama, and Hawaii, Seward oversaw the annexation of only one, that of the Brook Islands in 1867. Despite minimal Congressional support, though, he developed American influence in the Hawaiian Islands, as well as in Japan and China to some extent. His belief in expansion led him to pursue the purchase of British Columbia, an attempt to connect Alaska with the rest of the United States. Despite his endorsement of expansionist policies, Seward also strongly advocated non-interventionism. After Tsar Alexander II put down the 1863 January Uprising in Poland, French Emperor Napoleon III asked the United States to "join in a protest to the Tsar."[20] Seward declined, "defending 'our policy of nonintervention — straight, absolute, and peculiar as it may seem to other nations,'" and insisted that "[t]he American people must be content to recommend the cause of human progress by the wisdom with which they should exercise the powers of self-government, forbearing at all times, and in every way, from foreign alliances, intervention, and interference." Commodore Matthew Perry – the United States opened isolationist Japan to Western trade and influence when Perry landed there with American gunships in 1853. By the 1890s, Japan had become the first Asian Industrial Power, adopted Western ways and imperialist policies. Japan defeated China in 1894, and Russia in 1905, surprising the West (the U.S. & Europe). On March 31 1854 representatives of Japan and the United States signed a historic treaty. A United States naval officer, Commodore Matthew C. Perry, negotiated tirelessly for several months with Japanese officials to achieve the goal of opening the doors of trade with Japan. For two centuries, Japanese ports were closed to all but a few Dutch and Chinese traders. The United States hoped Japan would agree to open certain ports so American vessels could begin to trade with the mysterious island kingdom. In addition to interest in the Japanese market, America needed Japanese ports to replenish coal and supplies for the commercial whaling fleet. On July 8,1853 four black ships led by USS Powhatan and commanded by Commodore Matthew Perry, anchored at Edo (Tokyo) Bay. Never before had the Japanese seen ships steaming with smoke. They thought the ships were "giant dragons puffing smoke." They did not know that steamboats existed and were shocked by the number and size of the guns on board the ships. At age 60, Matthew Perry had a long and distinguished naval career. He knew that the mission to Japan would be his most significant accomplishment. He brought a letter from the President of the United States, Millard Fillmore, to the Emperor of Japan. He waited with his armed ships and refused to see any of the lesser dignitaries sent by the Japanese, insisting on dealing only with the highest emissaries of the Emperor. The Japanese government realized that their country was in no position to defend itself against a foreign power, and Japan could not retain its isolation policy without risking war. On March 31, 1854, after weeks of long and tiresome talks, Perry received what he had so dearly worked for--a treaty with Japan. The treaty provided for: 1. 2. 3. 4. Peace and friendship between the United States and Japan. Opening of two ports to American ships at Shimoda and Hakodate Help for any American ships wrecked on the Japanese coast and protection for shipwrecked persons Permission for American ships to buy supplies, coal, water, and other necessary provisions in Japanese ports. After the signing of the treaty, the Japanese invited the Americans to a feast. The Americans admired the courtesy and politeness of their hosts, and thought very highly of the rich Japanese culture. Commodore Perry broke down barriers that separated Japan from the rest of the world. Today the Japanese celebrate his expedition with annual black ship festivals. Perry lived in Newport, Rhode Island, which also celebrates a Black Ship festival in July. In Perry's honor, Newport has become Shimoda's sister city. Frederick Jackson Turner – The Closing of the American Frontier (1893) – produced concerns of loss of opportunities and the impact on democracy and the American character. He was an American historian best known for his book, The Significance of the Frontier in American History, in which he presented his "Frontier Thesis." This central thesis was that the vitality of the American spirit rested on westward expansion. Turner, who was chosen to speak in Chicago during the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, told his audience that all the land in the American western frontier had been explored and settled, and the great era of expansion appeared to be over. He assured his audience, however, that expansion could continue as long as the U.S. broadened its notion of "manifest destiny" and looked beyond its continental borders toward the rest of the world. This message was of great importance to a nation that was increasingly coming to value imperial expansion. Josiah Strong – wrote Our Country (1885); Anglo-Saxons were to superior to all other races and Americans were the most superior Anglo-Saxons – his book served as justification for American actions. A clergyman and writer who preached of the saving power of Protestant religious values. He is best known for his book, Our Country: Its Possible Future and Its Present Crisis, in which he urged Anglo-Saxons to "civilize and Christianize" the American West. In 1885, Josiah Strong wrote Our Country. In the book, Strong called for Anglo-Saxons to spread their superior institutions and values to "inferior races" in the American West. Civilizing "savages," he said, would be both good for the uncivilized peoples and for the American economy. Many of those in favor of global expansion in the late nineteenth century found inspiration in this work. Henry Cabot Lodge – believed in America’s superiority and the right for America to engage in conquest and expand; key figure in annexing the Philippines and a key player in the defeat of US membership in the League of Nations; the Lodge Corollary (1912) prevented Latin American countries from selling any of their lands to non-European countries. Friend of Theodore Roosevelt, strong supporter of imperialism. Investigated the conduct of the U.S. Army in suppressing rebels in the Philippines. Alfred T. Mahan – The Influence of Sea Power on History (1890) – nations must expand or die; the key to expansion was naval power – promoter of the Great White Fleet; the US needed colonies, coaling stations, a large navy, and an isthmian canal. Hawaii, Philippines, and a canal in Panama were keys to becoming a world power. President of the Naval War College, and leading advocate for imperial expansion. He argued that for a country to be a world power, it needed a powerful navy. He believed we needed Pacific Trade routes, a canal through Central America, and to dominate the Caribbean. Theodore Roosevelt – Before he became president, Teddy led the "Rough Riders," a volunteer cavalry in the Battle of San Juan Hill near Santiago, Cuba, making him an American Hero. As president, Roosevelt negotiated a peaceful end to the Russo-Japanese War with the Treaty of Portsmouth (1905) winning him the Nobel Peace Prize. Provided national leadership; saw the importance of the Pacific to American interests in the 20th century; Saw Germany and Japan as rivals of the US in the Pacific; With the Roosevelt Corollary – the US became the “policeman of the Western Hemisphere.” Sanford Dole – led a reform movement that forced the king of Hawaii, Kalakaua, to sign the "Bayonet Constitution" in 1887. It stripped the king of his power, limited the voting rights of the nobles and Native Hawaiians, and gave more power to the European and American subjects of the kingdom. The king died in 1893, leaving his sister, Lili'uokalani, as queen. She was overthrown by a group of businessmen calling themselves the Committee of Safety. Dole led a provisional government while its representatives sought annexation by the United States. Dole become president of the Republic of Hawai'i on July 4, 1894. A counter-revolution, led by the queen, failed to remove the new government. The annexationists within the republic continued their push, and after the election of U.S. President William McKinley, Hawaii was annexed as a territory in 1898. First and only President of the Republic of Hawaii; was a successful diplomat achieved recognition of the Republic of Hawaii and helped to secure the annexation of Hawaii in 1898 John Hay – author of the Open Door Policy (1900); opened Chinese treaty ports to equal trading opportunities for all nations while preserving Chinese territorial integrity. U.S. Secretary of State - wanted to protect American businessmen and investors in China. He worried that European powers would shut out American trade from China, which he saw as a vital market for the U.S. In 1899, Hay announced the "Open Door" Policy, giving equal trading rights to all foreign nations in China. He sent notes to all the other major powers and declared his policy to be in effect. The Boxer Rebellion erupted, led by a group opposing Western influence in China. The U.S. helped to crush this rebellion and opposed attempts by other nations to use it as an excuse to dismember China. Missionaries - with a belief in racial superiority, they argued that the United States had a responsibility to spread Christianity and "civilization" to the world's "inferior peoples."