What We know Can Change The Future

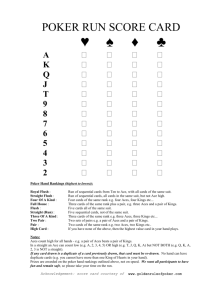

advertisement

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): What We Know Can Change the Future Linda Chamberlain, Ph.D. MPH State of Alaska Family Violence Prevention Project Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, DPH, DHSS www.ACEsconnection.com Please follow our work by joining: “DV and ACEs in the Arctic” Group What We’re Talking About •Framework of Resilience and Hope •Original ACE Study and Alaska ACE data •Effects of ACEs start early •Best practices and resources –Key characteristics of evidence-based interventions →Two-generation approach resources →Self-regulation skills Resilience Framework • Resiliency buffers the effects of trauma • Social support builds resilience across the lifespan • Trauma-informed care increases the effectiveness of health services • Helping parents to understand how ACEs can affect their parenting and children can prevent intergenerational trauma Capacity to adapt, cope and thrive during tough times = RESILIENCE – Resilience does not happen all by itself… – Resilience happens in the context of systems—family, schools, community... ACEs Can Be Overcome Why Focus on Resilience? • Protective factors can have stronger influence on how children who grow up with adversities do than specific risk factors – Remain consistent across different ethnic, social class, geographical & historical boundaries Rutter, 1987, 2000; Werner, 2001; Bernard, 2004 Children’s Response to Trauma is influenced by: –Characteristics of child –Frequency, severity, proximity of trauma –Community cohesion and collective support, family access to outside supports –Quality of parenting, parents’ response to trauma 6 RESILIENCE ACEs → ? TOXIC STRESS BRAIN ↓ STOP Toxic Stress Response Depressed immune system Chronic inflammation Physical health Mental problems health problems Self- medicate to cope Adopt risky behaviors Insights about Trauma • “Not realizing that children exposed to inescapable, overwhelming stress may act out their pain, that they may misbehave, not listen to us, or seek our attention in all the wrong ways, can lead us to punish these children for their misbehavior. The behavior is so willful, so intentional. She controlled herself yesterday, she can control herself today. If we only knew what happened last night, or this morning before she got to school, we would be shielding the same child we’re Playing a Poor Hand reprimanding.” Well, Mark Katz Trauma through a Different Lens Self-awareness is a key step in healing It’s not about what’s wrong with me, it’s about understanding what happened to me. Show of Hands • How many of you have heard of the ACE Study? • How many of you are currently talking with clients about ACEs? 10 The Original “ACE” Study •Large, collaborative study at Kaiser Permanente with CDC to examine the medical, social, and economic consequences of childhood adversities over the lifespan •ACE questions integrated into adult health history questionnaire Felitti et al, 1998 What Are Adverse Childhood Experiences? Positive answer to any questions for each type of ACE counts as one to create the ACE Score Based on Robert Wood Johnson Info-graphic at http://www.rwjf.org/en/about-rwjf/newsroom/newsroom-content/2013/05/Infographic-The-Truth-AboutACEs.html Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences in “Original” ACE Study Abuse, by Category Psychological (by parents) Physical (by parents) Sexual (anyone) Prevalence (%) 11% 28% 22% Neglect, by Category Emotional Physical 15% 10% Household Dysfunction, by Category Alcoholism or drug use in home Loss of biological parent < age 18 Depression or mental illness in home Mother treated violently Imprisoned household member 27% 23% 17% 13% 5% ACEs Are Good Buddies ACE Score Prevalence 0 33% 1 25% 2 15% 3 10% 4 6% 5 or more 11% If any one ACE is present, there is an 87% chance at least one other category of ACE is present, and 50% chance of 3 or >. Based on Robert Wood Johnson Info-graphic at http://www.rwjf.org/en/about-rwjf/newsroom/newsroom-content/2013/05/Infographic-The-Truth-AboutACEs.html Alaska ACE Data Sources • Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) • Telephone survey, 18 years or older • Questions on neglect added in 2014 • National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) • Telephone survey of households with at least one child < 18 years old; one child randomly selected as subject of parental interview • State-level data on the prevalence of selected ACEs among children – Excludes child abuse & neglect ACEs in Alaska (2013 BRFSS) ACE Score Prevalence 0 35.6% 1 22.3% 2 14.7% 3 10.1% 4 6.5% 5 or more 10.8% 5 or More ACEs by Age Group Age (Yrs) Prevalence 18-24 10.0% 25-34 12.1% 35-44 15.2% 45-54 12.0% 55+ 6.5% Adverse Childhood Experiences* Alaska Native Non-Alaska Native Abuse % % Emotional 37.8% 29.8% Physical 23.9% 18.3% Sexual 21.9% 13.6% *Percentages in red are significantly different between Alaska Native and Non-Alaska Native. Source: Alaska data from the 2013 Alaska Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, Alaska Department of Health and Social Services, Division of Public Health, Section of Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Adverse Childhood Experience* Alaska Native Non-Alaska Native Household Dysfunction % % Mental Illness in the Home 25.2% 21.3% Incarcerated Family Member 19.5% 10.1% Substance Abuse in Home 49.8% 31.0% Separation or Divorce 39.4% 30.4% Witnessed Domestic Violence 33.0% 16.2% *Percentages in red are significantly different between Alaska Native and Non-Alaska Native. Source: Alaska data from the 2013 Alaska Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, Alaska Department of Health and Social Services, Division of Public Health, Section of Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion National Survey of Children’s Health 2011/2012 Ace Question U.S. Statistically Alaska Significant Family's income hard to cover the basics like food or housing? Very often or Somewhat 25.7% 25.0% often. No Did child ever live with a parent or guardian who got divorced or separated after he or she was born? 20.1% 23.8% Yes Did the child ever live with a parent or guardian who died? 3.1% 3.1% NA Did ever live with a parent or guardian who served time in jail or prison after he/she was 6.9% born? 9.6% Yes Did the child ever see or hear any parents, guardians, or any other adults in his/her home slap, hit, kick, punch, or beat each other up? 7.3% 8.6% No Was the child ever the victim of violence or witness any violence in his/her neighborhood? 8.6% 10.5% No Did the child ever live with anyone who was mentally ill or suicidal, or severely depressed for more than a couple of weeks? 8.6% 11.0% No Did the child ever live with anyone who had a problem with alcohol or drugs? 10.7% 14.5% Yes Was the child ever treated or judged unfairly because of his/her race or ethnic group? 4.1% No http://childhealthdata.org/learn/NSCH 4.9% Two or More Adverse Childhood Experiences Highest Quintile Second Highest Quintile Middle Quintile Second Lowest Quintile 25.8% Lowest Quintile Range: 16.3% (NJ)-32.9% (OK) The Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health is a project of the Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (CAHMI) supported by Cooperative Agreement 1-U59-MC06980-01 from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB). With funding and direction from MCHB, these surveys were conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics. CAHMI is responsible for the analyses, interpretations, presentations and conclusions included on this site. Map created by Alaska Mental Health Board Staff Age 0-5 Years Old by Number of ACES in Alaska Zero ACEs 59.8% One ACE 24.7% Two or More ACEs 15.5% Source: National Survey of Children’s Health 2011/2012, Graphic created by the Alaska Mental Health Board/Advisory Board on Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Staff. Age 6-11 Year Olds by Number of ACES in Alaska Zero ACEs 48.1% One ACE 24.9% Two or More ACEs 27.0% Source: National Survey of Children’s Health 2011/2012, Graphic created by the Alaska Mental Health Board/Advisory Board on Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Staff. Age 12-17 Year Olds by Number of ACES in Alaska Zero ACEs 38.3% One ACE 26.1% Two or More ACEs 35.6% Source: National Survey of Children’s Health 2011/2012, Graphic created by the Alaska Mental Health Board/Advisory Board on Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Staff. Alaskan Children with One or More Emotional, Behavioral or Developmental Issues by ACE Score 30.0% 25.0% Percentage 20.0% 15.0% 14.2% 10.0% 5.0% 0.0% 5.6% 2.5% Zero One Two or More ACE Score Source : National Survey of Children's Health. NSCH 2011/12. Data query from the Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health website. Retrieved [08/24/2015] from www.childhealthdata.org Slide Prepared by Alaska Mental Health Board and Advisory Board on Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Staff Alaskan Children with More, Less and No Complex Health Care Needs by ACE Score 100.0% 90.0% 23.0% 28.4% 80.0% 46.5% 70.0% Two or More ACES Percentage 25.3% 60.0% 24.9% One ACE 50.0% 24.6% 40.0% 30.0% 51.7% 20.0% No ACES 46.7% 28.9% 10.0% 0.0% Children with No Special Health Care Needs Children with Less Complex Special Health Care Needs Children with More Complex Special Health Care Needs Source : National Survey of Children's Health. NSCH 2011/12. Data query from the Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health website. Retrieved [08/24/2015] from www.childhealthdata.org Slide Prepared by Alaska Mental Health Board and Advisory Board on Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Staff Alaska Children's Medical Home Status by ACE Score 100 18.4 90 80 32.8 Percentage 70 26.1 60 Two or more One 24.4 50 40 Zero 30 20 55.5 42.9 10 0 Care does not meet all medical home criteria Medical home--all criteria are met Source : National Survey of Children's Health. NSCH 2011/12. Data query from the Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health website. Retrieved [08/24/2015] from www.childhealthdata.org Slide Prepared by Alaska Mental Health Board and Advisory Board on Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Staff Effects of ACEs Can Start Early Increase risk of: Childhood obesity Early age at first intercourse Teen pregnancy Bullying Dating violence Fighting and carrying weapon to school Early initiation of tobacco use Early initiation of drug abuse Early initiation of alcohol use Self-mutilation and suicide Anda et al, 2002; Anda et al, 1999; Boynton-Jarrett et al, 2010; Dube et al, 2006; Dube et al, 2003; Duke et all, 2010; Hillis et al, 2001; Miller et al, 2011 School Readiness Children with 3 or more ACEs are nearly 4 times (OR=3.66) more likely to have developmental delays (Marie-Mitchell et al, 2013) Children with 4 or more ACEs are 32 times more likely to have behavioral problems in school (Burke et al, 2011) Children with 2 or more ACEs are 2.67 times more likely to repeat a grade (Bethel et al, 2014) ACEs and Childhood Obesity •Young children with an ACE score of 4 or greater are twice as likely to have a body mass index (BMI) ≥85% (Burke et al, 2011) •Children exposed to domestic violence are 80% more likely to be obese at age 5 years (Boynton-Jarrett et al, 2010) Prevalence of 2 or More ACEs among Children with Selected Health/Health Risk Factors* Health Factor 2 or more ACEs (%) Asthma 33.4% ADHD 45.2% Autism spectrum disorder 34.4% Behavior problem 61.4% Who bully 55.4% NCHS data which excludes abuse & neglect, includes exposure to community violence, poverty and discrimination; Bethel et al, 2014; *CSHCN SCREENER (Children with Special Health Care Needs); 5 domains Childhood Adversities and Psychiatric Disorders Among Adolescents Among adolescents, childhood adversities account for: –15.7% of fear disorders –32.2% of distress disorders –34.4% of substance use orders –40.7% of behavior disorders Population attributable risk proportions (PARPs) were predictive across DSM-IV disorder classes in this national sample ( n= 6483) McLaughlin et al, 2012 ACEs AND TEEN ALCOHOL USE Teens exposed to ACEs are more likely to: - to start drinking alcohol by age 14 -binge drink -say that they drank to cope during their first year of drinking Dube et al, 2006 Suicide Prevention Must Address ACEs • 80% of childhood and adolescent attempted suicides are attributable to ACEs * Attributable Risk Fraction (ARF) calculated in Study by Dube et al, 2001 Dube et al,2001 NATIONAL REVIEW OF BEST PRACTICES www.promisingfutureswithoutviolence.org Key Characteristics of Evidence-Based Practices for Children Exposed to Violence and Other Trauma • Caregiver involvement and support – Emphasis on trauma-informed parenting skills • Anxiety and stress management strategies for child and parent • Children’s social and emotional regulation skills – Identify and express emotions in safe ways – Construct trauma narrative/share story • Empowerment training www.promisingfutureswithoutviolence.org; NCJFCJ TA Bulletin; Buffington et al, 2010 Key Findings • Wide range of community-based interventions including some services provided by non-clinical staff – Domestic violence shelters (adapted TF-CBT) – School-based ( ARC, CBITS) – Homeless shelters (CARE) • Innovative practices such as therapeutic play and art-based interventions (PAL) • Parenting interventions including mothering (MotherCraft) and fathering after domestic violence (“Caring Dads”) Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) • Individual and joint sessions with child and parent (usually 12-16 sessions) to address childhood PTSD • Adapted for Native American and Alaska Native children • 8-session adaptation evaluated with DV-exposed children (Cohen et al, 2011) – ↓ in children’s DV-related PTSD and anxiety www.pittsburghchildtrauma.org Kids’ Club and Mom’s Empowerment • 10-week intervention with mothers & children (ages 6-12) • Multi-component approach – Parent training with behavior management – Social skills training with children • RCT results indicated 79% clinical range externalizing scores & 77% internalizing scores for children in mother-child intervention group • Pilots planned in Alaska Graham-Bermann et al, 2007 Structured Psychotherapy for Adolescents Responding to Chronic Stress (SPARCS) • Skill-based, present focused group psychotherapy for teens living with ongoing stress/trauma • 16 one-hour sessions by therapists offered in variety of community settings; adaptations include: – Shorter 6-session – Two peer-led curricula • EB-practice pilots have shown decreased risk behaviors, reduced trauma symptoms, and improved overall functioning www.nctsnet.org Collective Impact Framework Opportunities to integrate and expand availability of services, teach resilience-promoting skills: – Trauma-informed schools (ARC [Attachment, SelfRegulation & Competency]; CBITS) – Shelter-based programs (Kids’ Club, adapted TF-CBT, CARE) – Perinatal programs, home visitation, parenting classes – Juvenile justice, DOC … Collective Impact= structured approach to collaborative work across many sectors to achieve significant and lasting change on complex issues “Science tells us that interventions that strengthen the capacity of families and communities to protect young children from the disruptive effects of toxic stress are likely to promote healthier brain development and enhanced physical and mental wellbeing.” - American Academy of Pediatrics Planting the Seed •Many parents may not recognize how early trauma can affect their parenting and how they react to stressful situations •Increasing parents’ awareness about the effects of ACEs can help them to understand their own lives and make healthier choices to protect their own children from ACEs When we reach out and support children and their parents together, we see far greater results than the sum of their parts Two Generation Approach, Aspen Institute Is This Science? •Lots of hugs and affection •Reading/telling stories •Playing imaginary games •Singing songs •Helping child at mealtime and bedtime •Toys with movable parts Suglia et al, 2009 5 Core Principles of Trauma-Informed Parenting 1. Meet parents where they are at in terms of their life experiences and build on their strengths 2. Help parents/caregivers understand how experiences they had as children can affect their well-being and how they parent 3. Help parents/caregivers to recognize that ACEs can affect children in many different ways 4. Coach parents on positive discipline and parenting strategies that promote resilience 5. Offer tools to help parents/caregivers manage stress Chamberlain L. in ACEs: Best Practices, AVA, 2015 Caregiver Resource • Positive, supportive approach to help parents understand how trauma can affect their health, parenting & children • Universal education with self-assessment • Simple language to convey core concepts • Practical strategies to reduce stress and promote protective factors for parents and children (scannable QR codes) Contact jo.gottschalk@alaska.gov for free copies or go to www.healthfederation.org to download free PDFs of Amazing Brain Series Two-Generation Approach Meeting Parents Where They Are At and Providing Tools to Down-Regulate and Manage Stress Promoting Resilience •Self-Regulation •Attachment •Empathy •Competence Self-Regulation with Children “Neuroscience suggests that mediating the impact of adverse childhood experiences involves not only the education and emotional and practice support but also the introduction and application of neurological repair methods such as mindfulness training.” Bryck et al, 2012 Expanding Evidence Base: Mindfulness Practices and Children • Reductions in attention problems & anxiety (Lee et al, 2008; Semple et al, 2010) • Changes in brain activity (↓theta/beta ratios-EEG) and improved ADHD symptoms after 3 months (Travis et al, 2011) • Reduced anxiety, enhanced social skills and academic performance among adolescents with learning disabilities (Beauchemin et al, 2008) • Decreased aggressive behavior and bullying among students diagnosed with conduct disorder (Singh et al, 2007) Resilience Skills Being able to stay calm and in control when faced with a challenge mitigates the effect of trauma among children with special health care needs who had 2 or more ACEs -1.5 times more like to be engaged in school -half as likely to repeat a grade compared to those not exhibiting resilience NSCH data, Bethel et al, 2014 Lessons from Head Start, Trauma Smart • Children need simple strategies to calm their amygdala • Deep breathing helps children to focus and calm down Juanita Cabrales: 3 year olds Practicing mindful breathing Progressive Relaxation for Children Listen carefully and do what I say, even if it sounds silly. Pay attention to your body—think about how your muscles feel when they are all wound up and tight and when they are loose and relaxed. 1. You are a furry, lazy cat and you want to stretch…stretch your arms out in front, now high above your head, higher and way back, now drop your arms to the side, let’s try again and touch the ceiling 2. Be a turtle and go in and out of your shell 3. You have lemons in your hands, squeeze hard to get all the juice out, now let go, squeeze again, now drop the lemon…-------- 4. Fly on your nose---no hands! 5. Here come elephants and your tummy is the bridge! One elephant, two elephants…. Adapted from www.yourfamilyclinic.com “Sitting meditation seems to be an effective intervention in the treatment of physiologic, psychosocial and behavioral conditions among youth [ages 6 to 18 years old].” Systematic evidence review by Black et al. published In Pediatrics 2009 Seated meditation refers to sitting in a comfortable position, closing your eyes and focusing on breathing or a specific word of choice. MindUP Warm-UP: Inner and Outer Stillness •Sit in a comfortable position & make sure your shoulders are relaxed. •Relax your jaw; let your eyelids get heavy; close your eyes if you want to. •Notice your breath coming in and going out. Don’t try to change it! •Feel your stomach rising and falling. Let your belly be soft and relaxed. •Now see if you can breath a little more slowly and a little more deeply. •If your mind gets distracted, go back to noticing your breath. •Open your eyes slowly, take a deep breath and smile. MindUP Curriculum, Grades 6-8; Scholastic, 2011; lesson 3; pg 45. Mindfulness-Based Parenting Interventions •Parallel 8-week training for children (ages 8-12 y.o.) with ADHD and their parents demonstrated reductions parentreported stress and overreactivity and teacher-reported ODD behavior (Van Der Oord et al, 2012) •8-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) randomized trial with parents of children with developmental delays indicated significantly less stress and depression as well as greater life satisfaction while children had improvement in attention problems & ADHD symptoms (Neece, 2014) Yoga Curricula for Self-Regulation and Stress Management Autism and Special Needs Curriculum • Intentionally designed as CD so children focus on how it feels vs. how it looks • Each movement followed by breathing break • Movement illustrated by Shanti the Monkey Flip chart & coloring page • Can be done seated or standing http://greentreeyoga.org/programs/trauma-sensative-yoga/item/16trauma-sensitive-yoga-for-kids Attachment Attachment Can Be A Juggling Act • Dysregulated child rarely communicates needs in clear, direct manner • Helping caregivers to look for the real meaning behind the message—”I hate you!” → “I need a hug” • Responding to what the child needs vs. “deserves” based on behavior • FOCUS ON THE RELATIONSHIP vs. THE BEHAVIOR – →can go back to that after intense feelings have been calmed and connection is re-established Even the Small Stuff Changes -Terra Bovingdon “There’s a bit difference between attention- seeking behavior and children seeking connection.” Avis Smith, Head Start Trauma Smart When the BRAIN feels “heard” it will naturally move towards adapting and changing. TAKE THE LEAD, LOOK PAST THE BEHAVIOR AND FIND THE HIDDEN NEED. Tera Bovingdon, Attachment expert Connected Kids: Parent Video and Safety Card