Slide 1 - Vanderbilt University Medical Center

MODERN OBSTETRICS

COMES TO VANDERBILT:

A PERSONAL HISTORICAL

PERSPECTIVE

Frank H. Boehm, M.D.

Birth of Modern Obstetrics

The process leading to significant improvement in the care and outcome of pregnant women and their babies had its birth in the late 1960s and became fully developed in the 1970s.

Maternal Mortality in 1930

670 deaths per 100,000 live births

Maternal Mortality in 1982

7.5 deaths per 100,000 live births

Perinatal Mortality

1940

1965

2004

60/1,000

41/1,000

7/1,000

Infant Mortality

1940

1997

47/1,000

8/1,000

Electronic Fetal Monitoring

1972 – Purchase of 5 EF monitors and a blood gas analyzer at cost of $50K

L & D renamed Fetal Intensive Care Unit

All patients in labor underwent EFM with scalp pH sampling PRN

Monitor conference, Mondays at 4 pm began

Southern Med J

1974; 67:1145.

Contemp Ob/Gyn

1977;9: 57

VANDERBILT OB

1972

60 deliveries per month

Most low-risk patients

AMA - 1971

Adopted a position supporting the regionalization of perinatal care. In

1972, ACOG/AAP developed guidelines on how to evolve regionalization.

Ideally, it was recommended that whenever possible, pregnant mothers should be transferred before delivery, so as to provide the unborn child with the best incubator (the mother's uterus) during transfer.

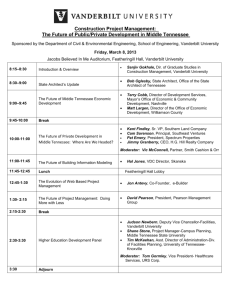

Perinatal Regionalization involved the transfer of high-risk newborns from smaller hospitals to larger, better-equipped and staffed neonatal intensive care units for their care following delivery. It also involved the transfer of high-risk pregnant women to tertiary hospitals, like Vanderbilt, prior to delivery, so they could receive the most sophisticated and advanced treatments available.

It was determined that delivery in a hospital appropriately staffed and equipped for all problems that might arise would result in better outcomes.

Regionalization of perinatal health care required the organization of a region,

(in our case, middle Tennessee), in which there were defined levels of perinatal care consisting of at least one tertiary care (Level 3) hospital, whose primary concerns were education, consultation, transportation and a high level of care.

Level 1 care hospitals (small rural hospitals throughout the 39 counties of middle Tennessee), described care given to normal obstetric patients and normal newborns

Level 2 care described care given for somewhat more complicated pregnancies and newborn illnesses

(Murfreesboro, Clarksville, Columbia,

Cookeville Hospitals).

Being a tertiary care facility, Vanderbilt

University Hospital was able to provide the Level 3 care required for the most complicated and sick pregnant patients and their newborns.

Important aspects of the regionalization process was the prevention of expensive duplication of health care services and staff as well as to provide the most sophisticated and technologically advanced care by highly trained health care providers.

The task for Vanderbilt was to convince doctors and administrators in small rural hospitals throughout surrounding counties of Nashville, to send to

Vanderbilt Hospital their sick newborns, as well as their complicated pregnancies, so that improved outcomes could materialize

Initial telephone calls to practicing

Obstetricians in some of the hospitals around Nashville to explain the benefits of Perinatal Regionalization were not productive.

I soon realized that convincing physicians to transfer care of their patients (and income) to Vanderbilt

Hospital would take a face-to-face encounter in their office, as well as a visit to the administrator of the hospital who would also be affected by a loss of patient care dollars.

With that in mind, I paid a visit to Dr.

Eugene Fowinkle, the then Tennessee

State Commissioner of Health, to ask for his support. I explained the importance of Perinatal Regionalization and how this process would not only save lives, but would also save considerable duplication of equipment and personnel in hospitals throughout the state.

Dr. Fowinkle did not hesitate. He instructed me to write a proposal outlining the costs and said he would do what he could.

Three months later, the State of

Tennessee awarded Vanderbilt's

Ob/Gyn Department $20,000 a year for two years thus allowing me to travel to each hospital in middle Tennessee in hopes of convincing doctors to send their high risk pregnant patients to

Vanderbilt rather than trying to care for them in their local community hospitals.

Convincing doctors to accept Perinatal

Regionalization once I arrived in their picturesque cities, however, was not as pretty.

Local doctors resented Vanderbilt

Hospital for the way some of its staff had treated them whenever they attempted to call for a consult or when they sent a critically ill patient to

Vanderbilt for special care. Many referring doctors explained how physicians at Vanderbilt were often condescending or arrogant when asked their advice.

I was told that when these local doctors did refer patients to Vanderbilt, their patient were lost to follow up. No one at

Vanderbilt, it seemed, made an attempt to inform referring physicians as to what had happened to their patients.

To add insult to injury, I was told of patients having returned home following treatment at Vanderbilt, telling their local doctors of disparaging comments made by

Vanderbilt staff about the care they had received prior to transfer.

It was with this in mind that we began to stress to the many doctors and nurses in the department of Ob/Gyn at

Vanderbilt, the importance of our relationships with referring doctors throughout middle Tennessee.

Insisting on direct Vanderbilt attending physician to referring physician consultation, we were able to gain control of our communication with physicians in middle Tennessee and slowly began to change opinions of our referral base of doctors.

Putting into place a system that emphasized rapid verbal and written communication to keep referring doctors updated on their patients after transport to Vanderbilt, as well as making certain that none of our staff made negative comments concerning care patients had received prior to transfer, was helpful in beginning a process whereby doctors began feeling comfortable referring their complicated pregnant patients to Vanderbilt

Hospital for specialized care.

Unfortunately, not everyone was pleased with our attempts to regionalize the care of pregnant patients.

Slowly and steadily, however, the number of high-risk obstetric patient referral for in-patient care began coming to Vanderbilt Medical Center with numbers reaching as high as 700 each year.

As early as 1981, Vanderbilt was able to report that survival of very small infants born at Vanderbilt Medical

Center had doubled during the years

1975 and 1980

Perinatal mortality (babies dying around the time of birth) in Tennessee, which was 31.2 babies per 1000 births in 1970, steadily declined to 15.8 by

1983.

Maternal mortality (mothers dying because of pregnancy complications) also declined during this time, from 2.9 pregnant patients per 10,000 pregnancies to 1.3.

Am J Obstet Gynecol

1979; 134: 484

J Tenn Med Assoc

1979;72:829

Most doctors and nurses needed an ongoing educational process that would involve on-site education on a regular basis. We needed a team of educators who would travel to hospitals around

Nashville to provide education on the use and interpretation of fetal monitoring.

Our department turned to the March of

Dimes and requested money to hire a nurse specialist who would be able to spend her days traveling throughout middle Tennessee in order to teach nurses the art and science of fetal monitoring.

JOGN Nursing

1981; 141:451

J Gynecol Obstet Nursing

1978;7 :29

J Tenn Med Assoc

1977;70:326

We also requested enough money to purchase Xerox telecopiers for each hospital as well as one for our labor and delivery suite and my home, thereby allowing physicians to transmit strips of their patient's fetal heart rate tracings for rapid consultation

Obstet Gynecol

1973; 42:475

Obstet Gynecol

1979; 53:520

We also began receiving an even larger number of outpatient referrals to the

Vanderbilt Clinics. Patients were being sent to our clinics for consultations on how to manage their complicated pregnancies. Patients requesting genetic counseling and testing increased rapidly as was our need for ultrasound examinations of pregnant women.

Establishment of the

Diabetes Mellitus

Antepartum Clinic

1976

South Med J

1978;71:37

J Perinatology

1985; Vol. V; 1

During this time there did not seem to be anyone in our Vanderbilt Radiology

Department who was interested in the new and very exciting technology of ultrasonography.

We needed someone at Vanderbilt to step forward and help bring this technology to the bedside.

That someone did appear. It was, however, not a faculty member, but rather a very junior resident, Dr. Arthur

Fleischer who came to my office one day to tell me that he understood the capabilities and possibilities of ultrasound.

Radiol

1981; 141: 163

Am J Obstet Gynecol

1981; 141:153

J Tenn Med Assoc

1976;67:33

Obstet Gynecol

1986; 67: 566

Am J Obstet Gynecol

1989;160:586

Obstet Gynecol

1989; 74:338

This desire to deliver a baby in a home like atmosphere was becoming quite popular in many cities around the country. To keep up with this growing demand our obstetric staff requested the hospital administration to open birthing rooms (also called labor, delivery and recovery rooms (LDR)) on our newly constructed labor and delivery floor in the new 11 floor Hospital, which was scheduled to open in the fall of 1980.

Despite what seemed a reasonable request, opposition surfaced. Members of the anesthesia department were expressing concern that LDR rooms might impose an increased risk for laboring patients.

Anesthesiologists, providing pain relief for our laboring patients stated that any patient placed in one of the newly built LDR rooms should not have epidural anesthesia nor be given oxytocin during labor and should not be allowed to have the father of the baby attend the delivery without undergoing an educational process and signing an agreement to abide by a number of rules of behavior.

Fortunately, over time, with the help of print and electronic media, as well as continued pressure from patients, consumer groups and practicing obstetricians, Obstetric

Anesthesiologists were convinced that the

LDR process was a safe and rewarding experience and all of the once placed restrictions on patients wanting a birthing room experience were lifted.

Perinatol Neonatol

1986; 10: 25.

Abortions at Vanderbilt

Roe v Wade 1973

Planned Parenthood 1973 (Sept.)

Director Dr. Angus Crook

Gestational Age Limits 1980

Only Indicated Cases 1980

1978

Creation of Maternal Fetal Medicine

Division

Co-Directors:

Al Killam, M.D and Frank Boehm, M.D.

Fellows Trained

Jeffrey M. Barrett, MD

James E. Brown, MD

Salvatore Lombardi MD

Periclis Roussis, MD

Richard Rosemond, MD

Cornelia Graves, MD

Eric Dellinger, MD

Thomas Wheeler, MD

David Fox, MD

Tracy Papa, DO

Audrey Kang, MD

7/1/80-6/30/82

1/1/84-12/31/86

7/1/86-6/30/88

7/1/88-6/3-/90

7/1/90-6/30/92

7/1/91-6/30/93

7/1/92-6/30/94

7/1/93-6/30/95

7/1/94-6/30/96

7/1/95-6/30/97

7/1/96-6/30/98

Another significant obstacle to advancing the concept of modern obstetrics was our inability to care for obstetric patients in our labor and delivery rooms who were critically ill.

What we needed was the ability to provide this same type of medical intensive care to our pregnant patients on labor and delivery where highly trained obstetric doctors and nurses could continuously provide simultaneous modern obstetric technology with the technology of medical intensive care usually provided in surgical and medical intensive care units in other parts of the hospital.

With this in mind, I asked one of our first year

Maternal Fetal Medicine fellows, Dr. Connie

Graves if she would be interested in learning the art and science of medical and surgical intensive care and help us set up an intensive care unit for critically ill obstetric patients on the labor and delivery floor. After an enthusiastic yes, Dr. Graves began a three month rotation in Vanderbilt's surgical intensive care unit, under the supervision of its Director, Dr. John Morris.

What was also needed, however were obstetric nurses who had interest and skill to also care of these extremely complicated patients. One of our nurses, Nan Troiano, had an interest in this type of intensive care and began the task of selecting a group of obstetric nurses for intensive care training.

Ms Troiano, along with Dr. Graves, trained nurses as well as Ob/Gyn residents on how to properly take care of pregnant women requiring intensive care monitoring and treatment.

Thus began one of the country’s first

Obstetric Intensive Care Units providing care for critically ill pregnant women on a labor and delivery floor.

Dr. Connie Graves and Nan Troiano became Directors of our Obstetric

Intensive Care Unit and began taking care of approximately 50 patients a year.

Critical Care Obstetrics. Dildy GA, ed. 4

th

Ed. 2004; Blackwell; Malden.

Numerous other exciting programs began to surface at Vanderbilt Hospital as a result of the introduction of modern obstetrics. In 1982, the

Department of Obstetrics and

Gynecology received a grant to participate in a multicenter preterm birth prevention project.

Certain unborn babies become severely anemic because of Rh disease and may die as a result. Previous attempts to transfuse these fetuses using x-ray equipment were difficult and frequently unsuccessful.

In 1986, Vanderbilt doctors were able to directly transfuse a fetus while still in its mother's uterus. Real time ultrasound technology allowed doctors to direct a needle into the unborn's umbilical cord and directly transfuse blood into the anemic child with considerable success.

In January 1987, a Hendersonville,

Tennessee woman, Darlene Hawkins, gave birth at Vanderbilt Medical Center to the first quintuplets ever born in

Tennessee

The delivery came 24 weeks into the pregnancy with the babies weighing about 1 1/3 pounds each.

Tragically, only the first born, Stephen, survived, yet the event catapulted

Vanderbilt's Obstetric and Newborn services to a national audience.

We have kept in touch with the Hawkins family and, 16 years after his birth,

Vanderbilt's labor and delivery staff gave Stephen a birthday party at the hospital. Today he is a healthy and delightful young man.

The introduction of a new method for early prenatal testing called CVS

(chorionic villi sampling) made

Vanderbilt a pioneer in the field of early prenatal testing.

We were unwilling, however, to perform

CVS on pregnant patients without first gaining experience.

We therefore, requested that Planned

Parenthood of Nashville allow us to perform this procedure on women who were to undergo an abortion. Fifty patients at Planned Parenthood accepted a monetary gift allowing us the opportunity to perform and perfect this new and innovative procedure.

In 1987 our Obstetric Division began offering CVS to pregnant patients

Am J Obstet Gynecol

1993;168:1766

Since those early days, patients have come to Vanderbilt Medical Center from all parts of Tennessee and surrounding states and we have performed over

3,000 CVS procedures.

In 1987, the Vanderbilt Perinatal Parent

Education Program began formal classes to help children understand pregnancy so they could be prepared to witness the birth of a sibling. Many parents told us that watching siblings being born would be a learning experience for their children and would enhance the feeling of being a part of an important family and life cycle event.

Vanderbilt House Organ

1989

In 1990, doctors at Vanderbilt Medical

Center performed a surgical procedure called a cerclage on a patient who had just delivered an extremely premature twin. This was the first time such an operation, under these circumstances, had been performed in the United

States and it saved the life of a middle

Tennessee newborn.

J Reprod Med

1992;37 :986

In 1990, the Maternal Fetal Medicine

Division recruited Dr. Joseph Bruner to

Vanderbilt Medical Center in order for him to develop a fetal surgery program.

In-utero surgery of the unborn was becoming technologically feasible and a number of birth defects were amenable to surgical correction while the fetus remained in its mother's uterus.

Within seven years, Dr. Bruner and

Pediatric Neurosurgeon, Dr. Noel

Tulipan, performed the first in-utero surgical repair of fetal spina-bifida

This historic event was followed by 178 fetal surgical repairs of spina-bifida at

Vanderbilt Medical Center resulting in the publication of several landmark scientific publications pointing to some improvement in outcome for the newborn.

JAMA

1999;282:1819

The National Institutes of Medicine is now funding and sponsoring a randomized research project along with two other major teaching centers, to ascertain the evidence based scientific value of such a procedure based on rigid research criteria. This study is now in progress.

OC3 began March , 1999 at Vanderbilt

Centralized management of pregnant women infected with the human immunosuppressive virus (HIV) and delivering 150 babies not infected with the AIDS virus during the past 6 years

One of the first Certified Nurse Midwife programs in the area was added to our hospital and now delivers approximately

60 babies each month at Vanderbilt.

Vanderbilt's Division of Maternal Fetal

Medicine began in 1975 a yearly two day seminar called the High Risk

Obstetric Conference.

First guest speaker was Dr. Ed Hon, inventor of the electronic fetal monitor.

It has become the longest running, as well as the most attended, post graduate Obstetric course in America.

Modern obstetrics has improved the lives of countless mothers and babies over the past 34 years. I am confident that in the future the staff at Vanderbilt

Medical Center will continue to combine modern technology with a humane, family oriented approach to childbirth in an attempt to bring and maintain excellence and safety to the process of giving birth.