Chapter 7 - School of the Performing Arts

advertisement

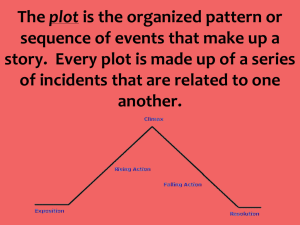

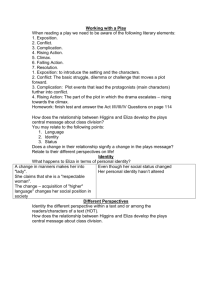

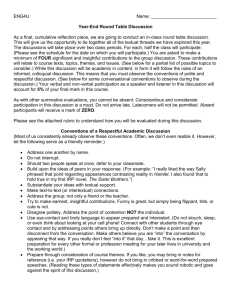

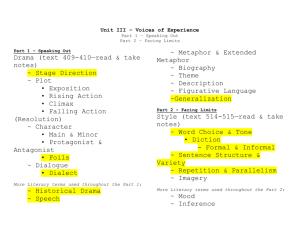

Chapter 7 – Drama’s Conventions All that lives by the fact of living, has a form, and by the same token must die—except the work of art which lives forever in so far as it is form. —Luigi Pirandello Chapter Summary • Playwrights have common strategies for developing plot, character, and action, for manipulating time, and for ending plays. • Taken all together, dramatic conventions are agreedupon ways to communicate information and experience to audiences. Writing Strategies: Stage Directions • Instructions for director, designers, and performers • Includes facts about: – Setting – Props and scenery – Music cues – General impressions of stage environment – Usually developed by playwright Writing Strategies: Stage Directions • Tennessee Williams’s stage directions for A Streetcar Named Desire (excerpt): The exterior of a two-story corner building on a street in New Orleans which is named Elysian Fields and runs between the L & N tracks and the river. The section is poor but, unlike corresponding sections in other American cities, it has a raffish charm. The houses are mostly white frame, weathered grey, with rickety outside stairs and galleries and quaintly ornamented gables. . . . Writing Strategies: Stage Directions • Shakespeare: – Information about time, place, mood presented mostly through dialogue (“weather lines”) – First 11 lines of Hamlet: • Place (“castle battlements”) • Time (“’Tis now struck twelve”) • Weather (“’Tis bitter cold”) • Mood (“I am sick at heart”) • Action (“Not a mouse stirring”) Writing Strategies: Exposition • Information about what’s going on, what has happened (antecedent action), and characters • Classical exposition: – Usually conveyed through dialogue – Often presented in formal prologue to action of play • Modern exposition: – Usually conveyed through dialogue – Less formal: information presented in casual exchanges between characters Writing Strategies: Point of Attack • Refers to moment early in the play when story begins • Macbeth: – Scene in which King Duncan learns of victory in battle – Point of departure for action of play Writing Strategies: Plot • Complication: – Unexpected development that increases emotional intensity – Usually toward middle of play • Crisis: – Turning point of action – Event that makes resolution of the plays conflict inevitable • Climax: – Moment at which conflict is resolved – Point of highest emotional intensity Writing Strategies: Plot • Resolutions and endings: – Restores balance to world of play – Satisfies audiences expectations – In absurdist plays, represented in completion of cycle Writing Strategies: Plot • Simultaneous plots: – Two stories told concurrently – Used to represent life’s variety and complexity – Secondary plot (subplot) resolved before main plot Conventions of Time: Dramatic vs. Actual Time • Audiences experience time on different levels: – Actual duration of play – Dramatic time (time span covered in world of play) • In play, time may be expanded or compressed: – Time may jump forward or backward by months, years. – Chronological sequence may be disrupted. • Unity of time (Aristotle): – Actions of play should unfold in real time. Conventions of Metaphor: Figurative Language • Metaphor: – Equating two unlike objects – “The moon is a balloon.” • Simile: – Comparing two unlike objects using like, as, than, or similar to – “The moon is like a balloon.” The Play-within-the-Play • A favorite technique of Elizabethan playwrights • Examples: – Shakespeare’s Hamlet: • Hamlet stages a performance of The Murder of Gonzago to assess Claudius’ guilt. – Brecht’s The Caucasian Chalk Circle: • Narrator links inner play (chalk-circle test) with outer play (dispute over land). The Play-within-the-Play • Modern applications: – Used to highlight life’s theatricality – Stage a metaphor for self-imposed illusions • Example: – Peter Weiss’s Marat/Sade: • Depicts production of a play by inmates of insane asylum Core Concepts • Drama’s conventions are a set of time-honored tools for communicating with audiences. • There are conventions for providing background information, manipulating time, ending plays, and telling more than one story at a time. • The insertion of an inner play within the larger one was a favorite device of Elizabethan writers to enliven the production’s theatrics. • In the modern theatre, the play-within-the-play is a means of demonstrating life’s theatricality.