Immigrants, Industry, and Urbanization

advertisement

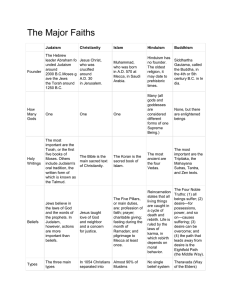

American Religion after the Civil War The years after the Civil War saw America transform from an agricultural society to an industrial economy based in the cities Population of major cities grew rapidly New York: appr. 1.1 million in 1860, 3.4 million in 1890 Chicago: appr. 100 in 1830, 1.6 million in 1900 Immigration also accelerated, with most settling in cities with industrial jobs Roughly 25 millions immigrants arrived within 50 years of the Civil War In 1890, as much as 80% of New York’s population was made of first or second generation immigrants Industrialization, immigration, and urbanization would have a major impact on America’s diverse religious culture Existing religious groups had to adapt their methods of organization and operation to the new cultural situation Religious groups, not the government, took responsibility for meeting new social welfare needs Immigration from new areas of Europe brought new religious orientations, even within pre-existent religious groups like Catholicism and Judaism Three examples illustrate the tension wrought by these changes: Number of Catholic adherents rose from 6.25 million in 1880 to 16.4 million in 1920, with Catholics accounting for over 60% of national growth Because most were immigrants, parishes normally divided along geographical lines were subdivided on ethnic, national, linguistic lines Catholic schools developed to educate immigrant children, distrusting the Protestant flavor of public schools Stress from this diversity had many implications: Inspired Americanism among native-born Catholics Challenged Catholic claims to universality because of dominant ethnic flavor of many parishes Presented problems when some eastern Europeans continued to follow the Eastern Rite and allow marriage among priests Caused backlash of anti-Catholicism, as in Josiah Strong’s Our Country Number of adherents to Judaism grew from 250,000 in 1880 to 3 million during WWI Because of isolation in various ethnic communities of Europe, form of practice differed among immigrants based on place of origin Joining the Reformed Judaism of the native born, who were embarrassed by immigrant practices, various strands developed in response to the American environment: Orthodox Judaism Conservative Judaism Secularism Zionism Like Catholics, Jews developed social networks and institutions to handle growth and sustain identity Longstanding Russian Orthodox communities existed in the American West and in Alaska Jobs in the mining industry attracted Orthodox Christians of various additional strands: Greek Orthodox Syrian Orthodox Armenian Orthodox Each strand continued to sustain its distinct form of practice Groups like the Young Men’s Christian Association provided training and a platform for social action Revivalists like D.L. Moody and Billy Sunday called individuals to return to the holiness sustained before problems of urbanization and industrialization arose Concern for social welfare inspired groups like the Salvation Army, but also caused some churches--“institutional churches”—to expand services to meet urban needs (e.g., gyms, education, housing, etc.) Underlying Protestant responses to new challenges were two different perspectives on the locus for change Some remained convinced that conversion of individual souls would lead in turn to social change D.L. Moody Billy Sunday Others believed the problems were too great for an individual approach, and that activists should target the social structures directly Social Gospel Walter Rauschenbusch Washington Gladden The common thread through this period, however, was optimism, a conviction that challenges could be met, society reformed, an Eden established on earth.