Chapter 15 and 16 Notes

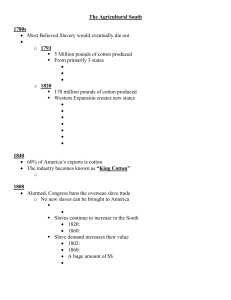

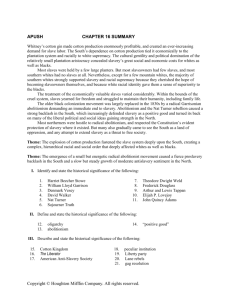

advertisement

Chapter 15 About ¾ of the 23 million Americans went to church each week. Thomas Paine’s widely circulated book The Age of Reason (1794) declared that all churches were set up to, “terrify and enslave mankind, monopolize power, and profit.” Many of the Founding Fathers (Jefferson and Franklin especially) were Deists. Deists relied on reason rather than revelation, on science rather than the Bible. Deists did believe in a Supreme Being who had created a knowledgeable universe and endowed humans with a capacity for moral behavior. Through all of this religious liberalism, the Second Great Awakening roared through the country. In its wake were left many new sects as well as reforms such as prison reform, the temperance movement, the women’s ,movement, and the crusade to abolish slavery. People (as many as 25,000) would go to huge “camp meetings” that lasted for days to listen to preachers’ gospels. In 1830 Joseph Smith said that he received some golden plates from an angel, which he deciphered into the Book of Mormon and the Church of Latter-Day Saints (the Mormons) was launched. Non-Mormons were upset with some of the things that Smith was preaching, including accusations of polygamy. Smith and his brother were murdered in Carthage, IL The movement was near collapse until Brigham Young stepped in and moved the group to Utah. The settlement began to thrive as more and more followers made their way out to Utah. European settlers also came after Mormon missionaries spread their word in Europe. There were many people against schooling for everyone during this time. Wealthy Americans began to see the light as they thought people needed to be educated in order to vote responsibly. Horace Mann, sec. of MA Board of Education, stepped in and pushed for more and better schoolhouses, longer school terms, higher pay for teachers, and expanded curriculum. As late as 1860, the nation counted only about a hundred public secondary schools- and nearly a million white adult illiterates. Black slaves were legally prohibited from learning to read and write. Free blacks in the North and South were usually excluded from the schools. Many new colleges and universities popped up across the country during this time. Most of the time, these places were built more out of community pride than as institutions of higher learning. The education was mostly left to men, as the woman’s place was in the home. Oberlin College bucked the trend as it admitted both women and black men in 1837. The same year, Mary Lyon established Mount Holyoke Seminary (later College) in MA. Custom, combined with hard and monotonous life, led to the excessive drinking of hard liquor by women, clergymen, and members of Congress. Weddings and funerals often became brawls and occasionally a drunken mourner would fall into the open grave with the corpse. After previous efforts, the American Temperance Society was formed in MA in 1826. Some people felt that others should stiffen their will to resist the little brown jug, while others felt that the temptation should be removed by legislation. The Maine Law of 1851, passed by Portland mayor Neal S. Dow, prohibited the manufacture and sale of intoxicating liquor. Dow is often called the “Father of Prohibition”. By 1857, 12 other states passed various prohibitory laws. Female reformers, most well-to-do, began fighting for temperance and the abolition of slavery. Prominent in the women’s rights movement were; Lucretia Mott Elizabeth Cady Stanton Susan B. Anthony Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell Margaret Fuller Sarah and Angelina Grimke Lucy Stone Amelia Bloomer These feminists met in 1848 in a memorable Women’s Rights Convention at Seneca Falls, New York. Stanton read a “Declaration of Sentiments,” which echoed the Declaration of Independence. Still, the crusade for women’s rights was overshadowed by the campaign against slavery. Chapter 16 People predicted that the iron logic of economics would eventually expose the unprofitability of slavery, spelling its demise. The introduction of Eli Whitney’s cotton gin in 1793 scrambled these predictions. As the use grew, cotton rapidly became the dominant southern crop, eclipsing tobacco, rice, and sugar. This explosion of cotton culture created an insatiable demand for labor. Quick profits drew planters to the loamy bottomlands of the Gulf states. As long as the soil was still rich, the yield was bountiful and the rewards were high. Northern shippers reaped a large part of the profits from the cotton trade. Cotton accounted for half the value of all American exports after 1840. The South produced more than half of the entire world’s supply of cotton. Britain was tied to America through cotton; If war were to break out between North and South, northern warships would cut off the outflow of cotton. The British factories would then close their gates and the London government would be forced to break the blockade and the South would triumph. In 1850 only 1,733 families owned more than 100 slaves each, and this select group provided the cream of the political and social leadership of the section and nation. Even in its best light, dominance by a favored aristocracy was basically undemocratic. It widened the gap between rich and poor and it also hampered tax-supported public education because the rich could send their children to private institutions. The plantation system also shaped the lives of southern women who commanded sizable household staff of female slaves. Quick cotton profits led to excessive cultivation or “land butchery”, which led to heavy population migration to the West and Northwest. This migration gave more and more land to large southern landowners. Cotton had its drawbacks as its price was determined by world conditions, as was the case when only one product was determined upon. Southern planters resented the Northern middlemen, bankers, agents, and shippers to whom they felt in servitude to for the rest of their lives because the North made most of what they owned. The South also repelled large-scale European immigration, which created manpower and wealth in the North. The South was the most Anglo-Saxon section of the nation. There were 250,000 free Southern blacks in 1860, many of whom owned property. The free blacks were kind of a “third race”; people who were prohibited from working in certain occupations and forbidden from testifying in court against whites. Also, they were always vulnerable from being hijacked back into slavery by slave traders. 250,000 free blacks lived in the North, where they were also unpopular. Several states forbade their entrance, most denied them the right to vote or to enroll in public schools. Much of the agitation in the North against the spread of slavery grew out of race prejudice, not humanitarianism. Antiblack feeling was in fact frequently stronger in the North than in the South. It was observed that white southerners, who were often suckled and reared by black nurses, liked the black as an individual, but despised the race. The white northerner, on the other hand, often professed to like the race but disliked individual blacks. Abolitionist sentiment first stirred at the time of the Revolution, especially among Quakers. Some early abolitionist movements focused on sending blacks back to Africa (American Colonization Society). The Republic of Liberia, on the West African coast, was founded for former slaves. By 1860 virtually all southern slaves were no longer Africans, but nativeborn African Americans, with their own distinctive history and culture. The first antislavery newspaper, The Liberator, was published in 1831 by William Lloyd Garrison. In 1833 the American Anti-Slavery Society was born. The greatest black abolitionist was Frederick Douglass, who escaped from bondage in 1838 at age 21.