File - Butch Hallmark

advertisement

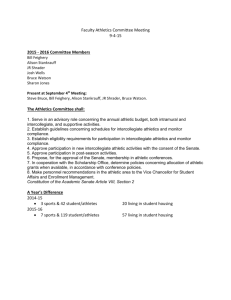

Running head: WOMEN’S ATHLETICS SINCE TITLE IX Women’s Collegiate Athletics since Title IX Butch Hallmark The University of Alabama 1 WOMEN’S ATHLETICS SINCE TITLE IX Introduction The purpose of Title IX is to prevent any federally funded program from discriminating against anyone from participating based on sex. Title IX is an extension of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and was enacted in 1972 as part of the Educational Amendments (Ambrosius, 2012). After the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was established, President Johnson signed an executive order that prohibited federal contractors from discriminating based on sex during the hiring process of new employees. This laid the ground work for gender equality legislation (Kwak, 2012). Title IX is most known for its involvement in collegiate athletics, but its reach extends to all aspects of federally funded entities and programs. The following is the key operative provision of the Title IX educational amendment states: No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance... Title IX was implemented in 1972 and the participation of women’s sports was very minimal (Ambrosius, 2012). However, in just four years, female participation in high school and collegiate sports rose six hundred percent and included around two million women (Ambrosius, 2012). When it was first implemented, universities were confused as to exactly how they should apply this to their university’s structure and how it would affect college athletics. Title IX’s regulations were created by the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare. This was a thorough set of standards that laid out the requirements for athletic programs. It was very clear that any gender discrimination would be considered a Title IX violation (Ambrosius, 2012). 2 WOMEN’S ATHLETICS SINCE TITLE IX Title IX compliance is made up of a “three-prong test” that schools may utilize to evaluate if the standards of Title IX have been met, which include: (1) Whether intercollegiate level participation opportunities for male and female students are provided in numbers substantially proportionate to their respective enrollments; or (2) Where the members of one sex have been and are underrepresented among intercollegiate athletes, whether the institution can show a history and continuing practice of program expansion which is demonstrably responsive to the developing interest and abilities of the members of that sex; or (3) Where the members of one sex are underrepresented among intercollegiate athletes, and the institution cannot show a continuing practice of program expansion such as that cited above, whether it can be demonstrated that the interests and abilities of the members of that sex have been fully and effectively accommodated by the present program. (Ambrosius, 2012, pp. 562-563) The first prong is easy for universities to comply with since that is the easiest for universities to measure and adjust accordingly (Ambrosius, 2012). The second prong is a little harder since expansion to different programs have only been occurring for such a short time (Ambrosius, 2012). The third prong is just as difficult as the second for universities to comply with, because if the university assumes they are providing adequate opportunities for both genders, one complaint under Title IX would show that it isn’t doing what it should for Title IX compliance (Ambrosius, 2012). 3 WOMEN’S ATHLETICS SINCE TITLE IX This research will also look at equity among both male and female athletes since Title IX’s implementation. In the harder financial times, many universities have had to consider the bottom line when it comes to Title IX compliance. So much influence in college athletic programs comes from its football program. Institutions with football programs are allowed between 63 and 85 scholarships for football alone, depending on the division of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) in which the school is participating. This means universities will need to increase women’s scholarships in athletics by adding more programs, or they will need to cut other men’s sports. This section will also look at the equity among white female athletes and black female athletes. How have the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Title IX worked together since 1972? The findings of a recent study by Pickett, Dawkins, and Braddock have found that black female athletes have not received the same benefits as their white counterparts in the same sports (2012). The next portion of this research will explore the different institution types that must comply with Title IX and its athletic programs. Twenty years after the Title IX implementation, studies showed that at most community colleges, they were not meeting the first prong of the compliance test (Staurowsky, 2009). Another study found that community colleges were meeting the requirement of having the same number of athletic teams for both men and women, but were failing regarding the catering of student interest and ability (Castaneda, Katsinas, & Hardy, 2008). There have also been quite a few monumental cases that have influenced Title IX and its place in collegiate athletics. The next section will look at a few cases that fell under Title IX arguments. One case involved an Ivy League institution quietly moving select women’s athletic teams from being funded by the university to being funded by donors. Another case involved a 4 WOMEN’S ATHLETICS SINCE TITLE IX very misogynistic athletic director not adding certain programs because he favored more feminine sports to sports like softball. The last case involved a male sport taking on the United States Department of Education because their, which included many universities, sport was being cut due to Title IX policies to allow the athletic departments keeping football as a sport, but not wanting to add women’s sports. The final section will explore different arguments for the support of Title IX and disapproval of Title IX. Brenda Ambrosius provides a great argument to keep Title IX in place (2012). Richard Epstein, on the other hand, provides very good arguments for repealing Title IX (2011). New arguments will come to light by the end of the research based on Ambrosius and Epstein. Equity since 1972 in Collegiate Athletics What athletes benefit from Title IX? This is a tough question, because Title IX was supposed to promote non-discrimination and equity among male and female athletes (Ambrosius, 2012). The only type of athlete that Title IX has helped since 1972 is women (Anderson & Cheslock, 2004). Football scholarships in 2012 amounted to 65 for current, returning players, allowing the school to allot 20 for high school seniors that are recruited by schools (Pitts & Rezek, 2011). That amount is for larger Bowl Championship Series (BCS) schools such as the University of Florida and the University of Texas (Pitts & Rezek, 2011). Additionally, schools will have other male sports such as tennis, wrestling, and basketball which all have scholarships awarded to at least some, if not all, of its members. This means that schools must allow the exact same number of scholarships for women’s sports. Because of this requirement, many schools award every participant in these sports a 5 WOMEN’S ATHLETICS SINCE TITLE IX scholarship just so it can meet the equity requirement (Ambrosius, 2012). This action led to the increase of collegiate women athletes from less than 15,000 in 1966 to over 190,000 in 2012 (Ladda, 2012). In a study conducted by Anderson and Cheslock, they found that institutions were more likely to add female teams or participants in order to move closer to compliance in the late 1990s and early 2000s (2004). Depending on the institution and financial strain its athletic program is facing however, women’s sports could be put on hold by institutions using other strategies (Anderson & Cheslock, 2004). Some universities may find that they are not in compliance with Title IX and need to balance the number of scholarships given to female and male athletes. With financial strain, universities may have to result to unfortunate measures. For example, a university needing to make budget cuts but increase the number of female athletic participation and scholarships may find themselves in a predicament since the budget will not allow for a new softball stadium to be built. The only other option would be to cut a men’s sport. This allows that university to make the participation and scholarship amount equal among the genders and would also allow them to keep football in-tact. This is very common among schools whose athletics program is new or doesn’t see the same success that the larger schools see (Anderson & Cheslock, 2004). In 2011, the University of Delaware (Delaware) announced that it would be using a similar strategy when it demoted the men’s track and cross country teams from varsity status to club status (Thomas, 2011). This meant that the Delaware athletic department no longer funded the team, and it would be moved to club status which meant it could still represent the university in athletic competition, but it would need to seek sponsors and donors (Ambrosius, 2012). The problem that is arising is the direction and attitudes toward Title IX compliance. With football being the largest sport in the country based on the amount of scholarship athletes 6 WOMEN’S ATHLETICS SINCE TITLE IX and members on the team, universities have found themselves trying to comply with a program that was supposed to create opportunities for women in the 1970s is now creating no opportunities for women and cutting men’s programs (Thomas, 2011). Delaware’s athletic director made a statement after mediation between the track team it cut and administrators that the “expansion of [the university’s] athletics program is not feasible in this financial climate, and given that reality, the university made the only decision it could,” (Thomas, 2011). In addition to equality among male and female athletes, females have to take into account another issue that is rising within college athletics. The equity among black female athletes and their white counterparts is not so equal. For example, the NCAA (2009) stated in the academic year of 2007-2008, the women’s sport in the United States with the highest net gain was lacrosse (as cited in Pickett, Dawkins, & Braddock, 2012). Because this sport’s majority of participants are white women, there are direct implications to sports whose majority is women of color (Pickett, Dawkins, & Braddock, 2012). Another strategy that universities use to comply with Title IX is the creation of obscure or nontraditional sports. This includes volleyball, rowing, and soccer (Pickett, Dawkins, & Braddock, 2012). Since the sports that attract mostly black females are basketball and track & field, the newer, nontraditional sports will attract mostly white females (Pickett, Dawkins, & Braddock, 2012). This presents a new battle for women of color. Not only do they need to work their way into collegiate athletics via Title IX, but they have to worry about the exclusivity of the sports they want to compete in (Rhoden, 2012). This can prove to be tricky for these athletes. No university will (publicly) say that they are discriminating based on race. However, it would be very hard to fight in a court case to prove that a university is in violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This means that women of color have to work harder in the sports they excel in already 7 WOMEN’S ATHLETICS SINCE TITLE IX to compete with white females. Black women have benefitted greatly from Title IX. However, white women have benefitted extremely well, more specifically suburban and wealthy white women (Rhoden, 2012). 2-Year Institutions vs. 4-year Institutions Athletic programs at 2-year institutions influence community and institutional pride. It actually can increase the number of enrollments as well (Causby, 2010). With 40% of higher education institutions consisting of community colleges and junior colleges, the fact that these athletics programs are not high profile doesn’t matter (Causby, 2010). It gives students a sense of community within the 2-year institutions and increases the pride of their school and gives them a better experience overall. There are some major differences between the ways 2-year institutions approach Title IX compliance and how 4-year institutions approach Title IX compliance. So far, we have seen 4year institutions make unfortunate decisions on what programs to cut in order to adhere to Title IX’s regulations and standards. Their main focus is toward sports that are male-dominated (Causby, 2010). 2-year institutions are actually driven toward female sports. Since community colleges do not have football teams, the only other sports that drive the athletic departments of these institutions are basketball for men and women, softball, and occasionally soccer/lacrosse depending on the region (Causby, 2010). Unfortunately, there are some disparities between male and female athletics at 2-year institutions across America. For example, in California community colleges, the proportionality between male and female athletes and the enrollment of the institution does not meet the first prong of the three-prong test used in testing the compliance with Title IX (Staurowsky, 2009). 8 WOMEN’S ATHLETICS SINCE TITLE IX Out of the 117 community colleges in the California community college system, only 8 percent reported they were meeting Title IX compliance expectations by having athletes within five percentage points of enrollment for each gender (Staurowsky, 2009). 4-year institutions focus their strategies on the more male-dominated approach to complying with Title IX. As this study found, universities would rather focus on the male sports than the female sports by cutting sports rather than creating new opportunities for women (Causby, 2010). The main difference between these institutions types is the driving forces of their athletic departments. With football being the most popular sport among the majority of the country, universities will keep that as priority. Instead of having to go through the extra cost of creating facilities for new women’s sports, it is easier for them to cut smaller men’s sports because of the disconnect between an institution’s academic and athletic agendas (Causby, 2010). This is not to say that the more successful athletic programs in 4-year institutions have not had their sports impacted positively by the implementation of Title IX (Ambrosius, 2012). Title IX’s legislation has enacted a lot of positive change in college athletic programs but it is misused because of the athletic departments focusing on football in 4-year institutions. Monumental Cases under Title IX The following are some of the monumental cases that fell under Title IX since its inception in 1972. First, the research breaks down the 1996 case of Cohen v. Brown. Second, the study looks at Pederson v. Louisiana State University. Next, we look at the very interesting case, National Wrestling Coaches Association (NWCA) v. United States Department of Education (DOE), in which the story is flipped in that it is men that were discriminated against because of 9 WOMEN’S ATHLETICS SINCE TITLE IX their gender. Finally, we look at the Mercer v. Duke University case, where a female was removed from the football team because of her gender. Cohen v. Brown University In November of 1996, Brown University was taken to federal court by female athletes who said the university discriminated against them when it changed the funding of the gymnastics and volleyball programs from university-funded to donor-funded. After doing so, the university defended its actions and then said they were in compliance with Title IX (Sidak, 1997). This goes back to the difference in 2-year institutions and 4-year institutions and the way 4-year institutions are more focused on male sports. Brown University believes that, based on national surveys and the amount of men in their institution, men are more interested in sports participation than women are (Sidak, 1997). Brown University had this idea of a quota system in which they needed to meet the expectations of the surveys issued. These were a bunch of unfortunate false assumptions that Brown University used to interpret Title IX compliance rules (Sidak, 1997). This could harm both genders. This could harm men because universities are already limiting the number of men that try out and make the team in order to meet the expectations of this quota system (Sidak, 1997). The end result of this case was that the federal courts ruled that Brown University did discriminate against the women because women comprise only 35 to 45 percent of Brown’s varsity athletes while they represent nearly 50 percent of the undergraduate enrollment (Sidak, 1997). Brown University tried to challenge this decision but was denied the appeal. Pederson v. Louisiana State University 10 WOMEN’S ATHLETICS SINCE TITLE IX In the 2000 case between female students and Louisiana State University (LSU), it may look like a typical Title IX case of female athletes being discriminated against by their university’s athletic department. When looking closer, we see that the athletic director is extremely misogynistic toward the athletes. His reasoning for not offering opportunities to female athletes that it does for male athletes is there was not enough interest and ability to add fast pitch softball and soccer teams (Pederson, et al. v. Louisiana State University, 1994). The plaintiffs were able to point to evidence in the court where the athletes faced sexism at the university. For example, the athletic director referred to one of the plaintiffs as “honey” and “sweetie” and said these things in the court room during proceedings (Pederson, et al. v. Louisiana State University, 1994). The same athletic director is on record for saying that he would have liked to add soccer since it was a more feminine sport, and that female soccer players “would look cute running around in their soccer shorts,” (Pederson, et al. v. Louisiana State University, 1994). The court found that LSU did in fact discriminate against its female students and was in violation of Title IX. The ruling was made that LSU should add the two women’s sports teams (Pederson, et al. v. Louisiana State University, 1994). This shows the attitudes that athletic departments have toward their female athletes at 4year institutions. Their focus is clearly on the male sports and it can be assumed that this athletic director’s opinion on women’s sports is that they should be cute and appealing. The fact that he said those things in and out of the courtroom proves that he doesn’t take women’s sports seriously. That is what Title IX is meant to prevent from happening. Its goals include increasing opportunities for women in college (athletic) programs and having these athletes treated the same as their male counterparts (Ambrosius, 2012). This win for these women and their sport was a huge win for feminists, not just Title IX advocates. 11 WOMEN’S ATHLETICS SINCE TITLE IX National Wrestling Coaches Association v. United States Department of Education The NWCA sought a reform of the Title IX educational amendment in that it actually discriminates toward men. The NWCA brought this to the courts because at some institutions, wrestling programs were being cut. Again, there is this idea that larger institutions are more male sport-focused, and instead of creating new opportunities for females, they cut non-traditional men’s programs so that it can keep funding for football and other male-dominated sports. The NWCA tried to prove this to the court, but failed to connect any instances of institutions dropping teams and Title IX policies (National Wrestling Coaches Association v. United States Department of Education, 2003). This resulted in the dismissal of the case. While this wasn’t a win for the NWCA and non-traditional men’s sports, the dialogue has continued because of it. In 2002, the DOE created the Secretary of Education’s Commission on Opportunity in Athletics (Hawes, 2003). They began to hear suggestions and recommendations from the NWCA and other sports organizations. In February of 2003, the commission delivered their recommendations based on the ones they received at their “summit” during the previous summer (Hawes, 2003). As of 2003, the DOE Secretary Rod Paige had not decided to make any changes to Title IX (Hawes, 2003). Mercer v. Duke University In 1994, Heather Mercer came to Duke University (Duke) having been an all-state placekicker at her high school. She anticipated trying out for the football team at Duke, and became the first female to try out for Duke’s football team. While she didn’t make it, she became the manager for the team. Mercer claimed that the coach made offensive comments about her 12 WOMEN’S ATHLETICS SINCE TITLE IX gender, which made her very uncomfortable. She was cut from the team in 1996 for reasons she claimed to be because of her sex. She lost the case against Duke, but won on appeal. This claim that Mercer made was in direct violation of Duke’s rules of athletics in that no person on the basis of sex shall be excluded from participation in a sport (Mercer v. Duke University, 1999). Duke’s arguments were that she was not talented enough to play in NCAA Division 1 football, but the jurors ruled that her sex was the reason for the way she was treated (Female Kicker's Suit is Good, 2000). A few years later, Jacksonville State University allowed a female place kicker named Ashley Martin on their team and she became the first female to ever score in an NCAA football game. Ashley’s experience and being allowed on the team may have been attributed to Mercer v. Duke. Arguments For and Against Title IX Disadvantages To begin, the key operative provision of the Title IX educational amendment states: No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance... This essentially requires that universities give women the same opportunity to participate in sports that they do for men (Epstein, 2011). This leads to some discouraging and sometimes extreme practices that universities utilize to comply with Title IX. Some of these practices lead into court cases. As mentioned in the previous section, the NWCA took on the DOE because since Title IX, the number of wrestling teams in college has been cut in half. Delaware cut its 13 WOMEN’S ATHLETICS SINCE TITLE IX varsity track team before it even fell out of compliance with Title IX. Universities are cutting back on the amount of eligible men until the participation rate is as low for men as it is for women. Another disadvantage is how is a transgendered student classified and how could a transgendered student athlete assist with Title IX compliance? The NCAA is currently studying the issue and has left the decision making as to which gendered team they should allow a transgendered person to participate in a sport (Jaschik, 2010). There are people expressing their opinion on this matter in which there are fears that people are switching genders for the purpose of winning spots and competition on women’s teams. Title IX doesn’t necessarily recognize gender identity. It only says “gender” and “sex” as its descriptors (Department of Education, 1972). The NCAA is performing an ongoing study and will hopefully make decisions on future policies that will be in the student-athlete’s best interest (Jaschik, 2010). This time for transgendered students is already a difficult time for them as it is. For community colleges, they do not have football to keep the male participation up with the proportionality to the school’s enrollment. There are a lot of female sports that are played at the community college level. However, it is difficult to find as many male sports to balance out. From 1990 to 2000, there was an increase of over thirty-three hundred female athletes and there was a decline of over twenty-three hundred of male participants during the same time. You can blame budget cuts, but it is because of Title IX (Castaneda, Katsinas, & Hardy, 2008). Advantages For 2-year institutions, they show commitment to achieving gender equity in funding the athletic-related aid. They also show an increase in commitment to increase the number of teams 14 WOMEN’S ATHLETICS SINCE TITLE IX they can sponsor. For community colleges, all athletics seem to be part of the driving force of school spirit and increased revenue for the institution. Since 2-year institutions serve more rural areas, both men’s and women’s sports are popular in the community. Local high schools will bring their teams to come watch games played at the institution. This could open the door for these high school students to see that they can earn a college degree and college can be funded by their skillset in a specific sport (Castaneda, Katsinas, & Hardy, 2008). At 4-year institutions with football programs, the focus is to keep the football program and adjust accordingly. However, at most schools with successful athletic programs, they will not cut men’s teams but create women’s sports and new opportunities for growth for women. One advantage with a lot of women’s sports is that universities can combine facilities with different sports. For example, a university could use an arena for women’s volleyball, women’s basketball, and men’s basketball. They could also turn the track and field stadium into a soccer stadium and have both housed there (Castaneda, Katsinas, & Hardy, 2008). Additionally, the way institutions can comply with Title IX is set up with the three-prong test in which an institution may choose the way they would like to comply (Ambrosius, 2012). Allowing schools to choose their option out of the three available options gives them more flexibility and provides higher compliance rates (Ambrosius, 2012). New compliance amendments to Title IX will offer more security to prospective athletes coming out of high school to college. Schools will be able to offer programs that are well sustained and competitive without focusing on the athletes’ gender (Ambrosius, 2012). This will turn the focus from universities focusing on a quota system to focusing on student, university, and community interest to satisfy Title IX compliance. 15 WOMEN’S ATHLETICS SINCE TITLE IX Conclusion Title IX has come a long way since 1972. Sometimes that “way” was backwards, then forwards, then back again. Unfortunately the bottom line for most universities trying to comply with the educational amendment is financial strain. The recent amendments made seem to have the students’ interest in mind. Based on the arguments presented by Epstein, Castaneda, Katsinas, & Hardy, some additional arguments and ideas could be presented to make Title IX more inclusive and fair for all genders. One thing is the inclusion of cheerleading into collegiate Title IX compliance. There is a new sport called STUNT that is groing across the country at the collegiate and high school levels that removes the crowd-leading element of cheerleading and focuses on the technical and athletic components of cheer. The creators of the sport are working closely with lawmakers and the Office of Civil Rights to ensure that it meets Title IX compliance and meets the guidelines of what exactly is a sport. Bringing STUNT, which is exclusive to females, to universities would help satisfy a lot of universities’ Title IX compliance issues. Additionally, the main cost would be scholarships. The universities could hold tryouts for the cheerleading squad, then from that group gauge an interest of who on the team would be interested in competing for STUNT. Their main focus would be STUNT and cheer occasionally at sporting events, while the females who didn’t make the STUNT team or was not interested could focus on the cheer elements. Title IX has a long way to go before it is perfected, if it ever is. Having universities that are cooperative and adaptable to change when Title IX goes through its evolution is going to be one of the biggest key factors to Title IX serving all students succesfully. Creating new opportunities for women at larger schools and for men at 2-year institutions, not cutting men’s 16 WOMEN’S ATHLETICS SINCE TITLE IX programs to comply with the law, and exploring unique options like STUNT to incorporate in their Title IX compliance could really improve the equity of collegiate athletics. 17 WOMEN’S ATHLETICS SINCE TITLE IX Bibliography Ambrosius, B. L. (2012). Title IX: Creating Unequal Equality Through Application of the Proportionality Standard in College Athletics. Valparaiso University Law Review, 557. Anderson, D. J., & Cheslock, J. J. (2004). Institutional Strategies to Achieve Gender Equity in Intercollegiate Athletics: Does Title IX Harm Male Athletes? American Economic Review, 307-311. Castaneda, C., Katsinas, S. G., & Hardy, D. E. (2008). Meeting the Challenge of Gender Equity in Community College Athletics. New Directions for Community Colleges, 93-105. Causby, C. S. (2010, June). Title IX Compliance at Two-Year Colleges: An Analysis of Perceived Barriers and Strategies. A Dissertation to the faculty of the Graduate Schoole of Western Carolina University. Education, D. o. (1972). Title IX. Education Amendments of 1972. Epstein, R. A. (2011). Repeal Title IX. Defining Ideas: A Hoover Institution Journal. Female Kicker's Suit is Good. (2000, October 13). The New York Times. Hawes, K. (2003, June 23). Wrestler's Title IX lawsut dismissed. Retrieved from National Collegiate Athletic Association: http://fs.ncaa.org/Docs/NCAANewsArchive/2003/Associationwide/wrestlers_%2Btitle%2Bix%2Blawsuit%2Bdismissed%2B-%2B6-23-03.html Jaschik, S. (2010). Transgender Athletes, College Teams. Inside Higher Ed. Kwak, S. (2012, May 7). Title IX Timeline. Sports Illustrated, 116(19). 18 WOMEN’S ATHLETICS SINCE TITLE IX Ladda, S. (2012). Examining Title IX at 40: Historical Development, Legal Implications, and Governance Structures. President's Council on Physical Fitness & Sports Research Digest, 10-20. Mercer v. Duke University, 99-1014 (U.S. 4th Circuit Court of Appeals July 12, 1999). National Wrestling Coaches Association v. United States Department of Education, 02-0072 (EGS) (United Staets District Court for the District of Columbia June 11, 2003). NCAA. (2009). 1981-82-2007-08 NCAA sports sponsorship and participation report. Indianapolis. Pederson, et al. v. Louisiana State University, 97-30427 (United States Court of Appeals 1994). Pickett, M. W., Dawkins, M. P., & Braddock, J. H. (2012, October 10). Race and Gender Equity in Sports: Have White and African American Females Benefited Equally From Title IX? American Behavioral Scientist, pp. 1581-1603. Pitts, J. D., & Rezek, J. P. (2011). Athletic Scholarships in Intercollegiate Football. Journal of Sports Economics, 515-535. doi:10.1177/1527002511409239 Rhoden, W. C. (2012, June 10). Black and White Women Far From Equal Under Title IX. The New York Times. Sidak, M. (1997, December 1). Brown University v. Cohen: A Pyrrhic Victory for Feminists. Civil Rights Practice Group Newsletter, 1(3). Staurowsky, E. J. (2009). Student Athletes and Athletics. New Directions for Community Colleges, 53-73. 19 WOMEN’S ATHLETICS SINCE TITLE IX Thomas, K. (2011, May 1). Colleges Cut Men's Programs to Satisfy Title IX. The New York Times. 20