Art 101-Ch 10

advertisement

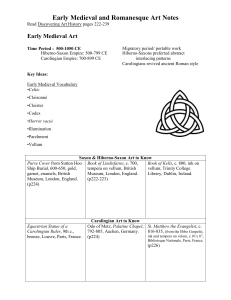

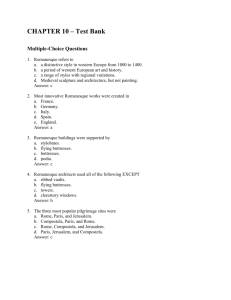

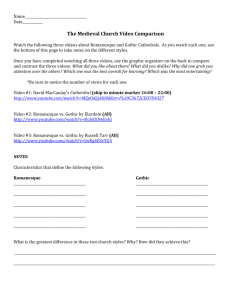

Early Medieval and Romanesque Art This manuscript painting, done about 1000 CE, is a scene of humility, but during the next 200 years, the Romanesque period, the emperors, kings, popes and abbots lavish their material resources on churches to glorify God and recreate an image of the heavenly Jerusalem on earth. As the Roman empire crumbled, political power passed to bishops and secular lords. The church, as the repository of tradition and learning, provided intellectual as well as spiritual leadership. The art of the tribes who were now in control of former Roman territories was developed from earlier Bronze and Iron Age people. Individual motifs include spirals, birds, humans, and dragonlike animals so interlaced that one has to look carefully to identify them. After the fall of Rome, British chieftains took control of England and Ireland with the help of soldiers from continental Europe (the source for the legends of King Arthur). The Angles, Saxons and Jutes from the continent (who had come to England) soon established kingdoms of their own and the people under their rule adopted AngloSaxon speech and customs. Metalworking is one of the glories of Anglo-Saxon art. References to interlacing metal jewelry is in Anglo-Saxon literature. An early 7th century burial mound excavated in 1939 at a site called Sutton Hoo (hoo means “hill”) revealed an 86 foot long ship with weapons, armor, and equipment for the afterlife. Some of the items were luxury items such as the purse cover and the epaulets. They are decorated with cloisonné enamel with designs from wide ranging sources. The rich blend of motifs represent a complex style that flourished in England and Ireland in the 7th and 8th century. As Christianity spread through the islands, Hiberno-Saxon (Hibernia is the ancient name for Ireland) scribes adapted pagan styles for large, lavishly decorated gospel books. On the Chi Rho Iota (XPI-an abbreviation for Christi, the first word in the Latin sentence that says “Now this is how the birth of Jesus Christ came about”) page from the Book of Kells, has interlacing and lots of symbolism, both pagan and Christian. Even as the monks were writing the Book of Kells, Vikings began to appear on the coasts of the British Isles, lured by the wealth of church treasuries and fertile land. They were a terrifying presence for nearly 300 years intermittently looting and destroying communities. The Franks had settled in northern Gaul (modern France) by the end of the 5th century. In 732, the Franks turned back the Muslim invasion of Gaul and established a dynasty of rulers called the Carolingians…the greatest being Charles the Great (Charlemagne). Charlemagne imposed Christianity, sometimes brutally, throughout his territory. In 800, Pope Leo III granted Charlemagne the title of emperor reinforcing Charlemagne’s authority and strengthening the bonds between the papacy and secular government in the West. Charlemagne turned to the Church to help stabilize his empire through religion and education. He looked to the Benedictine monks as his “cultural army.” Although their principal duties were prayer and liturgical services, monks and nuns spent hours producing books. The monasteries of northeastern France became the centers of book production during the reign of Charlemagne’s son, Louis the Pious. In the book of gospels made for Archbishop Ebbo we see the unique style that emerged there. Everything in this painting seems to be charged with spiritual excitement, even the top of the writing table seems about to fly off its pedestal. Only a wealthy monastery could afford a book. Hundreds of sheep had to be slaughtered to provide the pages, and hundreds of hours were needed to write each page. When the books were created, they were protected with heavy leather covered wooden and sometimes jeweled covers. Figures in low relief gold are hovering above the arms of the cross, and are in agony below the arms of the cross. The heirs of Louis the Pious divided the Carolingian into three parts. -The western portion eventually became France -The eastern part of the empire, roughly modern Germany, Switzerland and Austria, passed to a dynasty of rulers known as the Ottonians after three principal rulers named Otto. Otto I gained control of Italy in 951 and the pope crowned him emperor in 962. Thereafter, Otto and his successors dominated the Papacy and appointments to other high offices. In the 10th and 11th centuries, artists in northern Europe began a tradition of large sculpture in wood and bronze that would significantly influence later medieval art. Bishop Bernward was an important patron of the arts, and was also a skillful goldsmith. A pair of bronze doors, made under his direction, was the most ambitious bronze project undertaken since antiquity. The Bishop installed these bronze doors in 1015. Page 253 Standing over 16 feet tall, the doors are decorated with Old testament scenes on the left, and New Testament scenes on the right. Like their predecessors, monks and nuns of the Ottonian Period created richly illuminated manuscripts. Styles varied from place to place depending on the local traditions of the scriptorium and the models available in each library. This is an unusual presentation page from the Hitda Gospels of the early 11th century. Abbess Hitda presents her book to Saint Walpurga, the patron saint of her abby. The large architecture is arranged to draw attention to the figures and show the importance of the position of the Abbess. The simple contours of the figures, combined with the halo device framing them, recalls Byzantine art. Otto I began to incorporate parts of Italy into his empire, and by the 12th century, the Ottonian empire had become known as the Holy Roman Empire. The Ottonian court in Rome gave artists access to the artistic heritage of Italy. From this groundwork during the early medieval period emerged the arts of European Romanesque culture. At the end of the first millennium, the “feudal system” of landowners and landless but free peasants working for them started to change. Life changed from a largely agricultural economy to one where craft and trade allowed greater personal freedom and well-being. As inventions made farming easier and the population grew, people began to move into the growing towns and cities. The nations we know today did not exist in Medieval Europe. The pope in Rome, and the patriarch of Constantinople continued to be important players in European politics. French nobles were powerful and controlled the richest lands. But, French kings were consolidating personal territory around Paris and laying the groundwork for a powerful national monarchy. Southern France kept their own language and cultural traditions, while across the Pyrenees mountains, the Iberian peninsula was a battleground of Christians and Muslims during this period of “reconquest.” Normandy became a powerful feudal duchy. In 1066, William, the Duke of Normandy, invaded England, and, as William the Conqueror, became their king. William replaced the Anglo-Saxon nobility with Norman nobles, and England began to emerge as the nation it is today. William’s victory is recorded in the Bayeux Tapestry with scenes of war and celebration. By the 12th century, popular mass movements such as pilgrimages and the Crusades began to end European isolation. In 1095, Pope Urban II called for the first of several Crusades supposedly to “free” Jerusalem and the Holy Land from Islamic rule. For the most part, the Crusades were military failures. But, the contact of the Europeans with the sophisticated Byzantine and Islamic cultures introduced new ideas into Europe and created a demand for new products and luxury goods. Despite encountering dire physical and material handicaps on their journeys, people of all levels of society traveled to the holy places of Christendom. The three major shrines were the tomb of Christ (The Holy Sepulchre) in Jerusalem and the tombs of Saint Peter in Rome and Saint James in Santiago de Compostela. But, there were many local shrines as well. See page 257-CLOSER LOOK Pilgrims who went to holy sites or shrines went to venerate (show respect for) relics. Relics are the bodies of saints, parts of the bodies of saints or even something that had belonged to a saint. Relics are kept in richly decorated boxes or display cases called reliquaries. To accommodate the faithful and instruct them in church doctrine, many new large churches were built on the major pilgrimage routes. These churches were filled with sumptuous altars, crosses and reliquaries. Romanesque Architecture 1. Solid masonry walls 2. Rounded arches 3. Vaults characteristic of Roman buildings. Romanesque, cruciform Basilica Nave with rounded Romanesque arches- Barrel Vaults In the 12th century, Dover castle, safeguarding the coast of England from invasion, illustrates the way in which a key defensive position developed over the centuries. The Romans had built a lighthouse on the point, to which the Anglo Saxons had built a church. Earthworks protected to some degree, but the building of fireresistant walls was obvious. The Great Tower, as it was called in the Middle Ages, (but later known as a keep or a donjon), had a courtyard (bailey) surrounded by additional walls. Ditches added to the height of the walls,; in some castles, ditches were filled with water to make moats. The castle yard was filled with buildings. A hall for feasts and ceremonial occasions, timber buildings to house troops, servants and animals…barns and workshops…ovens and wells because the castle had to be self sufficient. Often a gatehouse and drawbridge controlled the entrance. If the castle of the secular lord was to be an imposing masonry structure, the house of God was equally powerful and impressive. Romanesque churches are often basilicas modified in significant aesthetic and structural ways. Designs varied from place to place, so there is no such thing as a “typical” Romanesque church. Romanesque builders used masonry as often as possible for its strength, resistance to fire and the acoustic properties for the Gregorian chants sung by the monks. In 1066, William the Conqueror, a Norman, conquered England. Later, Norman builders working in the north of England in Durham, made some significant structural innovations. Their system of vaulting was carried to the Norman homeland in France. Masons perfected this new vaulting system and it became the foundation of Gothic architecture. The most precious and admired arts of the Middle Ages are those that later critics called the “decorative arts.” Artists in the 11th and 12th centuries were often monks and nuns. They 1. Worked in the scriptorium as calligraphers and painters to produce books. 2. Created the metal, enamel and jewel work used in church services. 3. Embroidered the vestments, altar cloths, and wall hangings. The Bayeux Tapestry is an excellent 11th century historical document documenting the victory of the Norman Duke, William, over the British King Harold. The tapestry was probably a gift to the Bayeux Cathedral by Williams brother, Bishop Odo. The earliest known illustrated history book was written in the 12th century by a monk named John of Worchester. The pages here concern Henry I, second son of William to sit on the English throne. The text relates to dreams the king had in which his subjects demand tax relief. In the first night, angry farmers confront the sleeping king. On the second night armed knights surround the bed On the third night, monks, abbots and bishops present their case. John of Worchester, Page with Dream of Henry I, Worchester Chronicle, Worchester England. C. 1140, Ink and tempera on vellum, each page 12 ¾”X9 3/8”. Corpus Christi College, Oxford. Historians look at these illustrations for information about life in 12th century England, just as they look at the Bayeux Tapestry to learn about life in the 11th century. Here, the three classes of society are depicted in characteristic dress and carrying their equipment. The angry farmers, knights and clergy have come to the king in his dreams to demand tax relief. In the king’s fourth dream, he promised to rescind the tax for 7 years if God would save him from the storm at sea. This story came from a reliable source, the kings doctor, who is shown in the margins of the pages by three of the scenes. Although we most often study the most spectacular manuscripts, the majority of books were functional items with few or no illustrations. In the Romanesque period, as earlier in the Middle Ages, women were involved in the production of books as authors, scribes, painters and patrons. The nun, Guda, was both a scribe and a painter. In a book of homilies (sermons) she inserted her self portrait into the letter D and signed the image “Guda, a sinful woman, wrote and illuminated this book.” The importance of this selfportrait lies in its demonstration that women were far from anonymous workers. This image is the earliest signed self-portrait of a woman in Western Europe. Among the richest of the cloister crafts was metal working. The work of the metal smith might become a special kind of treasure when jewels donated by pilgrims were attached to a piece. One such piece is the reliquary statue of Saint Faith in Conques, France. It is a repository of gems from many periods. (See “Closer Look,” page 257. Not every church could afford works in precious metals and jewels. Wooden sculptures also satisfied the need for devotional images. Here, Mary is seated on a bench symbolizing the throne of Solomon who was known as a wise King. She then represents a throne for the Christ Child, and becomes the Throne of Wisdom. They are presented frontally and erect, as rigid as they are regal. Originally, Jesus held a book in his left hand and gave a blessing with his right hand.