MENS REA recklessness

advertisement

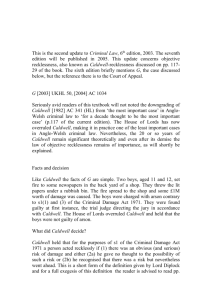

IH A2 Law MENS REA – RECKLESSNESS Recklessness is a lower level of mens rea than intention and means that the defendant knows that there is a risk of the consequence but then takes that risk anyway. Recklessness is only considered where it has been found that the defendant did not have the intention to cause the consequence which occurred. The current law on recklessness comes from the case of Cunningham (1957) which states that recklessness is a subjective test in that it depends on the particular defendant including all of his attributes and level of intelligence etc rather than looking at the reasonable man (objective test). Cunningham (1957) – D tore a gas meter from the wall of an empty flat to steal the money inside. In doing this, he damaged the gas pipe and gas seeped into the flat next door injuring the woman in the flat. Cunningham was charged with the criminal offence of ‘maliciously administering a noxious thing’ contrary to s23 Offences Against the Persons Act 1861. He was found to be not guilty of the offence because he did not realise the risk of gas escaping and therefore he had not intended to cause the harm and he had not taken the risk he knew about. In the legal sense of the word, maliciously means that to have the necessary mens rea D must either intend the consequence or realise that there was a risk of the consequence happening and decide to take that risk anyway. The case of Savage (1992) confirmed that this principle applies to all cases where the word ‘maliciously’ is used in an Act of Parliament to describe a part of the offence. An offence for which recklessness is sufficient for mens rea is assault occasioning actual bodily harm contrary to s47 Offences Against The Person Act 1861. The mens rea is intention or recklessness as to the assault or battery. There is no requirement that the defendant intended or was reckless as to the injury inflicted IH A2 Law PROBLEMS In the past, recklessness was a more complicated issue as there used to be 2 levels of recklessness: 1. Subjective – Where the defendant realised the risk, but decided to take it (as in Cunningham (1957)) 2. Objective – Where an ordinary, prudent person would have realised the risk, the defendant is guilty even if he did not realise the risk. This objective test came from the case of Metropolitan Police Commissioner v Caldwell (1981) and applied only to certain types of cases. This objective test received widespread criticism as it meant that even if the defendant himself had not realised that there was a risk involved in the actions that he was taking, he could still have the necessary mens rea for the offence. This caused particular problems where D had a condition which meant that they were not capable of contemplating the risk – Elliot v C (1983) was a case which involved a 14 year old girl with learning disabilities who did not understand that her actions would lead to a shed being set on fire. Nevertheless, she was convicted of the offence as the objective test of Caldwell recklessness meant that she had to be judged by the standard of an ordinary adult. This clearly illustrates that injustices were caused by the Caldwell recklessness test. Other criticisms were: Whilst criminal damage was subject to Caldwell recklessness, Cunningham recklessness applied to offences against the person and thus property was given a greater level of protection. The precise limits as to which offences required which type of recklessness were not fully understood or defined Having two definitions for the same word was confusing The test was difficult for juries to understand Having an objective test blurs the distinction between negligence and recklessness IH A2 Law Caldwell recklessness was eventually overruled by the House of Lords in the case of G and Another (2003) in which the defendants were two boys aged 11 and 12 who set fire to some bundles of newspapers and then threw them under a wheelie bin thinking that they would go out. They left the scene but a building caught fire and £1m damage was done. They were initially convicted under the Caldwell idea of recklessness but on appeal, the House of Lords overruled this saying that a defendant could not be guilty of an offence unless he had realised the risk and decided to take it. The House of Lords reaffirmed that the necessary test for recklessness is the subjective Cunningham test. This clarification however, does not mean that the law on recklessness is straight forward. Some people still criticise the subjective test as it is very difficult to prove what is the mind of the defendant at the time they committed the offence meaning that some defendants can escape liability just by arguing that they did not foresee the risk. However, as a matter of public policy, the idea that there should only be liability where there is fault is the overriding principle. Cunningham recklessness (Subjective) 1957 Present Day 1981 2003 Caldwell recklessness (Objective)