07ExaCt - Douglas Walton's

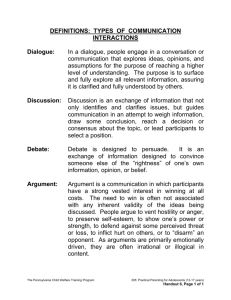

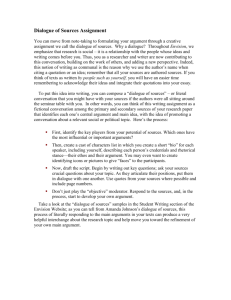

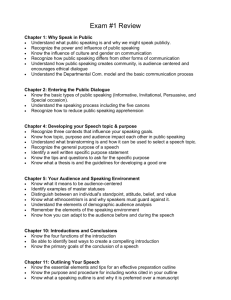

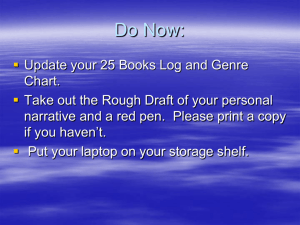

advertisement

Dialogical Models of Explanation ExaCt Vancouver July 21-22, 2007 Douglas Walton Example of a Hamblin Dialogue Each member in the sequence is defined by Hamblin (1971, p. 130) as a triple, n, p,l . n represents the length of the dialogue (the number of moves so far). p is a participant. And l is a what Hamblin calls a locution. Using Hamblin’s notation, a small dialogue with three moves for far could be represented as follows. Small Dialogue: 0, P0 , L4 ,1, P1, L3 ,2,P0, L2 In the simplest case, there are two participants, called the proponent and the respondent. When either party makes any move (speech act), the rules determine which statements are inserted into, or deleted from that participant’s commitment set. Rules define what kinds of moves can be made and what response move needs to be made just after the other party’s last move. Rules define when a sequence of dialogue successfully realizes the communal goal of the dialogue. Each party has a goal, and the dialogue as a whole has what can be called a communal goal. Dialogue Typology Dialogue Persuasion Critical Discussion Information Seeking Interview Negotiation Advice Solicitation Inquiry Scientific Inquiry Expert Consultation Deliberation Public Inquiry Eristic Quarrel Locutions and Speech Acts • • • • Statements and questions are locutions. Making an assertion is a speech act. Asking a question is a speech act. Asking for an explanation is an even more specific speech act. • Putting forward an argument is a speech act. • Offering an explanation is a speech act. Speech Act Moves in a Dialogue Goal of Dialogue Sequence of Moves Turn-taking Respondent's Move Speech Act Post-condition Proponent's Move Pre-condition Initial Situation Speech Act Evaluating Argumentation • Take the text of discourse as your evidence. • Is the selected speech act an argument, a report or an explanation? • If an argument, what are the premises and conclusions? • Does it fit an argumentation scheme? • Apply the scheme to the argument Reasoning, Argument and Explanation Reasoning can be used for differing purposes, for example in explanations and arguments. Reasoning is a process of inference in passing from certain propositions known or assumed to be true to other propositions in a sequence (Walton, 1990). Abductive reasoning is inference to the best explanation (Josephsons, 1994). Practical reasoning seeks out a prudential line of conduct for an agent in a particular situation, while theoretical reasoning seeks evidence that counts for or against the truth of a proposition (Walton, 1990). What is an Argument? An argument is a social and verbal means of trying to resolve, or at least contend with, a conflict or difference that has arisen between two parties engaged in a dialogue (Walton 1990, p. 411). According to this definition, an argument necessarily involves a claim that is advanced by one of the parties, typically an opinion that the one party has put forward as true, and that the other party questions. Asking Questions • The speech act of asking a question is different from the speech act of putting forward an argument. • Questions don’t make assertions. • But questions can be loaded. • So asking a question may not be entirely harmless or free from assertive content. What is an Explanation? The new dialectical theory (Walton, 2004) models an explanation as a dialogue between two agents in which one agent is presumed by a second agent to understand something, and the second agent asks a question meant to enable him to come to understand it as well. The model articulates the view of Scriven (2002, p. 49): “Explanation is literally and logically the process of filling in gaps in understanding, and to do this we must start out with some understanding of something.” How to Tell the Difference Test to judge whether a given text of discourse contains an argument or an explanation. Take the statement that is the thing to be proved or explained, and ask yourself the following question. Is it taken as an accepted fact, or something that is in doubt? If the former, it’s an explanation. If the latter, it’s an argument. The Goal of Dialogue is Different The purpose of an argument is to get the hearer to come to accept something that is doubtful or unsettled. The purpose of an explanation is to get him to understand something that he already accepts as a fact. Dialogue Model of Explanation • Dialogue Conditions: explainee asks question of a specific form asking about what is assumed to be a known fact S. • Understanding Conditions: explainee does not understand S, but assumes that explainer understands S. • Success Conditions: explainer by what she says brings the explainee to understand S. Explanation in a Sequence of Dialogue Event Taken as Factual by Both Parties Attempt Judged to be Successful or not by Respondent Something Perplexing to Respondent about Event Not Successful Explanation Dialogue Concluded Respondent asks Proponent for Help in Understanding Successful Proponent Offers Explanation Attempt Rules for CE Dialogue System • Opening: when explainee makes an explanation request for S (accepted fact). • Locution Rules: defines different speech acts (kinds of moves) that are allowed. • Dialogue Rules: show which move must follow each previous kind of move. • Success Rules: show when transfer of understanding has been achieved. • Closing: when explainee says ‘In understand it’ or explainer says ‘I can’t explain it’. Typical Profile of Explanation Dialogue Locution Speaker Content U(XE) U(XR) ExplanRequest(S) XE S Not-S S ExplanResponse(T) XR T ? T Understand S XE S S,T Dialogue Closes Problems for Future Work • How can we test whether understanding has successfully been transferred? • How can we evaluate whether one given explanation is better than another? • What is the structure of explanations of human (and artificial agent) actions? • What tools do we have for visualizing the logical structure of an explanation? What is the test whether understanding has been successfully transferred? • Scriven (1972, p. 32) Suggested an answer to this question in his remark quoted below.1] • How is it that we test comprehension or understanding of a theory? We ask the subject questions about it, questions of a particular kind. They must not merely request recovery of information that has been explicitly presented (that would test mere knowledge, as in knowing the time or knowing the age of the universe). They must instead test the capacity to answer new questions. • This remark suggests that the test is the explainee’s capacity to answer new questions, shown in a dialogue. • But what kind of dialogue is it? Examination Dialogue • The examiner puts questions to the examinee, keeps track of the examinee’s answers, and probes into them critically. • Examination dialogue is classified by Dunne, Doutre and Bench-Capon (2004), and Walton (2006) as a species of information-seeking type of dialog that can often shift to a persuasion dialog in which the questioner critically probes into the tenability of the respondent’s collective replies (Dunne, Doutre and Bench-Capon, 2004, p. 1560). • In this way, the formal structure of examination as a dialogue model can be applied to central features of the kind of cases of examination commonly found in trials in law. Shift from Explanation to Examination • We can test for the success (failure) of an explanation by asking the explainee questions about new situations that are similar to S or are extrapolated from S. • For example, if the explainee can draw a new inference from S that is reasonable, that is evidence he has understood S correctly. Example of a Dialectical Shift • Two agents have a joint intention to hang a picture. One has the picture and a hammer, and knows where the other can get a nail. They have a deliberation dialogue but can’t agree on who should do which task. They then shift to a negotiation dialogue in which the one agent proposes that he will hang the picture if the other agent will go and get the nail (Parsons and Jennings, 1997). Evaluating Competing Explanations • Car crash where passenger claimed driver lost control, and driver claimed passenger suddenly pulled handbrake (Dutch Supreme Court Case cited by Prakken and Renooij, 2001). • Evidence: skid marks, crashed car, handbrake found in pulled position, expert witness says pulling handbrakes can cause wheels to lock. • Analysis of Prakken and Renooij: the driver’s account explains the factual evidence and contradicts less of it than the passenger’s account. • For summary, see (Walton, 2004a, 170-175) Action Explanations • Explanations of actions, of the kind especially common in history and law, is based on goal-directed reasoning. • Goal-directed or means-end reasoning is called practical reasoning. • Practical reasoning has a special argumentation scheme. Indeed, it has two of them. Instrumental Scheme for Practical Reasoning • I have a goal G. • Bringing about A is necessary (or sufficient) for me to bring about G. • Therefore, I should (practically ought to) bring about A. Scheme for Value-based Practical Reasoning • I have a goal G. • G is supported by my set of values, V. • Bringing about A is necessary (or sufficient) for me to bring about G. • Therefore, I should (practically ought to) bring about A. The Scalpicin Example Araucaria Araucaria is a software tool for analyzing arguments. It aids a user in reconstructing and diagramming an argument using a simple point-and-click interface. The software also supports argumentation schemes, and provides a user-customizable set of schemes with which to analyze arguments. Once arguments have been analyzed they can be saved in a portable format called "AML", the Argument Markup Language, which is based on XML. http://www.computing.dundee.ac.uk/staff/creed/araucaria/ Some References P.E. Dunne, S. Doutre, and T.J.M. Bench-Capon, ‘Discovering Inconsistency through Examination Dialogues’, Proceedings IJCAI-05, Edinburgh, 2005, 1560-1561. S. Parsons and N. R. Jennings, ‘Negotiation through Argumentation: A Preliminary Report’, Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Multi-Agents Systems, ed. Mario Tokoro, AAAI Press, Menlo Park, California, 1997, 267-274. H. Prakken and S. Renooij, ‘Reconstructing Causal Reasoning about Evidence: A Case Study’, Legal Knowledge and Information Systems, ed. B. Verheij et al., Amsterdam, IOS Press, 131-142. M. Scriven, ‘The Concept of Comprehension: from Semantics to Software’, Language Comprehension and the Acquisition of Knowledge, ed. J.B. Carroll and R.O. Freedle, Washington, W. H. Winston & Sons, 1972, 31-39. M. Scriven, The Limits of Explication’, Argumentation, 16, 2002, 47-57. D. Walton, ‘A New Dialectical Theory of Explanation’, Philosophical Explorations, 7, 2004, 71-89. D. Walton, Abductive Reasoning, University of Alabama Press, 2004a. D. Walton, ‘Examination Dialogue: An Argumentation Framework for Critically Questioning an Expert Opinion’, Journal of Pragmatics, 38, 2006, 745-777.