skin_physiology_adva..

advertisement

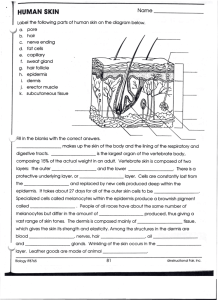

Skin Anatomy and Physiology Advanced Course Course Author—Dr. Patti Farris • Dr. Farris is a Nu Skin Professional Advisory Board Member. • She is a clinical assistant professor at Tulane and in private practice in Metairie, Louisiana. • She has authored twenty-five scientific publications and is known for her expertise in the treatment of aging skin. • She has appeared in over 200 health related television segments including appearances on CNN, NBC Weekend, and Regis and Kathie Lee. • She has been quoted extensively in magazines (e.g., Newsweek, Allure, In Style, and Oprah Magazine). Did You Know? Beautiful, healthy skin is determined by the healthy structure and proper function of components within the skin. Find out why in this course. Objectives After viewing this course, you should have an understanding of the following: • In-depth anatomy and physiology of the layers of the skin: hypodermis, dermis, and epidermis. • How skin health and beauty are determined by the healthy structure and function of the skin. Previous Curriculum Review In the Skin Anatomy and Physiology Basics course, you learned the following: • The six purposes of the skin: protection, thermoregulation, excretion, secretion, sensation, and vitamin synthesis. • The skin’s different layers: hypodermis, dermis, and epidermis. • Basic skin anatomy and physiology. Introduction Major Layers of the Skin Hypodermis: subcutaneous (just beneath the skin) fat that functions as insulation and padding for the body. Dermis: provides structure and support. Epidermis: functions as a protective shield for the body. Epidermis Dermis Hypodermis Let’s talk about each of these in greater detail, starting with the hypodermis. Muscle Hypodermis (deepest section) Hypodermis The hypodermis refers to the fat tissue below the dermis that insulates the body from cold temperatures and provides shock absorption. Fat cells of the hypodermis also store nutrients and energy. The hypodermis is thickest in the buttocks, palms of the hands, and soles of the feet. As we age, the hypodermis begins to atrophy, contributing to the thinning of aging skin. Hypodermis Dermis (between the hypodermis and epidermis) Dermis The dermis is a fibrous network of tissue that provides structure and resilience to the skin. Dermal thickness varies but is on average 2 mm thick. Major components of the dermis include the following: • • • • • Collagen. Elastin. Glycosaminoglycans. Blood and lymph vessels. Specialized cells: mast cells and fibroblasts. Epidermis Dermal epidermal junction Mast cell Dermis Elastin fiber Collagen fiber Glycosaminoglycans Blood vessels Fibroblast cell Dermis: Network of Structural Proteins The major components of the dermis work together as a network, composed of structural Mast proteins, blood and lymph vessels, cell and specialized cells. This mesh-like network is Elastin fiber surrounded by a gel-like substance called the ground substance, composed mostly of Collagen glycosaminoglycans. fiber Epidermis Dermal epidermal junction Dermis Glycosaminoglycans Blood vessels Fibroblast cell Dermis: Ground Substance The major components of the dermis are surrounded by a gellike material called the ground substance. This ground substance is composed of moisture-binding glycosaminoglycans and plays a critical role in the hydration and moisture levels within the skin. Epidermis Dermis Glycosaminoglycans Dermis: Collagen The most common structural component within the dermis is the protein collagen. It forms a mesh-like framework that gives the skin strength and flexibility. The glycosaminoglycans— moisture binding molecules— enable collagen fibers to retain water and provide moisture to Collagen the epidermis. fiber Epidermis Dermis Dermis: Elastin Another protein found throughout the dermis is the coillike protein, elastin, which gives skin the ability to return to its original shape after stretching (elasticity). Epidermis Elastin fiber Dermis Dermis: Fibroblasts Epidermis Both collagen and elastin proteins are produced in specialized cells called fibroblasts, located mostly in the upper edge of the dermis bordering the epidermis. Dermis Fibroblast cell Dermis: Mast Cells Intertwined throughout the dermis are blood vessels, lymph vessels, nerves, and mast cells. Mast cells are specialized cells that play an important role in triggering the skin’s inflammatory response to invading microorganisms, allergens, and physical injury. Epidermis Mast cell Dermis Dermis: Blood Vessels Blood vessels in the dermis: Epidermis • Help in thermoregulation (blood vessels constrict or dilate to conserve or release heat). • Aid in immune function (healing). Dermis • Provide oxygen and nutrients to the lower layers of the epidermis. Blood vessels Dermis: Blood Vessels Blood vessels do not extend into the epidermis. Nourishment that diffuses (seeps) into the epidermis only reaches the very bottom layers. For this reason, the cells in the upper layers of the epidermis are dead (because they do not receive oxygen and nutrients). Epidermis Dermis Blood vessels Dermis: Epidermal Junction The junction between the dermis and epidermis is a wave-like border that provides an increased surface area for the exchange of oxygen and nutrients between the two sections. Dermal epidermal junction Dermis: Dermal Papillae Along this junction are projections called dermal papillae. As one ages, the dermal papillae tend to flatten, decreasing the flow of oxygen and nutrients to the epidermis. Dermal epidermal junction Dermal papillae Epidermis (outermost layer) Epidermis The epidermis consists of anywhere between 50 cell layers (in thin areas) to 100 cell layers (in thick areas) and acts as a protective shield for the body. Skin cells within the epidermis are referred to as keratinocytes. Average epidermal thickness is 0.1 mm (about the thickness of one sheet of paper). Epidermis: Five Differentiated Layers The epidermis is composed of five horizontal layers: 1 - Stratum basale 2 - Stratum spinosum 3 - Stratum granulosum 4 - Stratum lucidum 5 - Stratum corneum 5 4 3 2 1 Epidermis: Stratum Basale Stratum Basale (germinative layer) • The deepest layer of the epidermis, sitting directly on top of the dermis, is a single layer of cubeshaped cells. 5 4 3 2 Stratum basale 1 Stratum Basale (continued) New epidermal skin cells, called keratinocytes, are formed in this layer through cell division to replace those shed continuously from the upper layers of the epidermis. This regenerative process is called skin cell renewal. Basal cells As we age, the rate of cell divide to renewal decreases. replace cells lost at the surface 5 4 3 2 1 Stratum Basale (continued) Melanocytes, found in the stratum basale, are responsible for the production of skin pigment (melanin). They transfer the melanin to nearby keratinocytes that will eventually migrate to the surface of the skin. Melanin is photoprotective: it helps protect the skin against ultraviolet radiation (sun exposure). Stratum basale 1 Melanocyte Epidermis: Stratum Spinosum Stratum Spinosum (pricklecell layer) • The stratum spinosum is composed of 8–10 layers of polygonal (many-sided) keratinocytes. • In this layer, keratinocytes are beginning to become somewhat flattened. Stratum spinosum 2 Epidermis: Stratum Granulosum Stratum Granulosum (granular layer) • Composed of 3–5 layers of flattened keratinocytes. • In this layer, keratin—a tough, fibrous protein that gives skin its protective properties—begins to form inside the keratinocytes. • Cells in this layer are too far from the dermis to receive nutrients through diffusion, so they begin to die. Stratum granulosum Keratin 3 Epidermis: Stratum Lucidum Stratum Lucidum (clear layer) • The stratum lucidum is present only in the fingertips, palms, and soles of the feet. • It is 3–5 layers of extremely flattened cells. Stratum lucidum 4 Epidermis: Stratum Corneum Stratum Corneum (horny layer) • The top, outermost layer of the epidermis, the stratum corneum, is 25–30 layers of flattened, dead keratinocytes. • The stratum corneum layer is the real protective layer of the skin. Stratum corneum 5 Stratum Corneum (continued) Keratinocytes in the stratum corneum are continuously shed by friction and replaced by the cells formed in the deeper sections of the epidermis (stratum basale). The epidermis totally renews itself approximately every 28 days. Stratum corneum Stratum Corneum (continued) In between the keratinocytes in the stratum corneum are epidermal lipids (ceramides, fatty acids, and lipids) that act as a cement (or mortar) between the skin cells (bricks). Epidermal lipids Stratum Corneum: Moisture Barrier This combination of keratinocytes with interspersed epidermal lipids (brick and mortar) forms a waterproof moisture barrier that minimizes transepidermal water loss (TEWL) to keep moisture in the skin. The composition of these lipids in the moisture barrier is: ceramides (40%), fatty acids (25%), and cholesterol (25%). Stratum corneum can be referred to as the moisture barrier Stratum Corneum: Moisture Barrier (continued) The moisture barrier protects against invading microorganisms, chemical irritants, and allergens. If the integrity of the moisture barrier is compromised, the skin will become vulnerable to dryness, itching, redness, stinging, and many other skin care concerns. Keeps microbes, irritants, and allergen out. Stratum Corneum: Acid Mantle (pH 4.5 to 6.5) In the very outer layers of the stratum corneum, the moisture barrier has a slightly acidic pH (4.5 to 6.5). These slightly acidic layers of the moisture barrier are called the acid mantle. The acidity is due to a combination of secretions from the sebaceous and sweat glands. Acid mantle Stratum Corneum: Acid Mantle (continued) The acid mantle functions to inhibit the growth of harmful bacteria and fungi. The acidity also helps maintain the hardness of keratin proteins, keeping them tightly bound together. If the skin’s surface is alkaline, keratin fibers loosen and soften, losing their protective properties. Inhibits bacteria and other microbes Acid mantle Stratum Corneum: Acid Mantle (continued) When the pH of the acid mantle is disrupted (becomes alkaline)—a side-effect of common soaps—the skin becomes prone to infection, dehydration, roughness, irritation, and noticeable flaking. (pH 4.5 to 6.5) Acid mantle Skin Components Common to Dermis and Epidermis Skin Components Common to Dermis and Epidermis There are a number of components common to both the dermis and the epidermis. • Pores • Hair • Sebaceous glands • Sweat glands Pore Sebaceous gland Epidermis Hair follicle Dermis Sweat gland Blood vessels Pores Pores are formed by a folding in of the epidermis into the dermis. The skin cells that line the pore (keratinocytes) are continuously shed, just like the cells of the epidermis at the top of the skin. The keratinocytes being shed from the lining of the pore can mix with sebum and clog the pore. This is the precursor to acne. If oil builds up inside the pore, or if tissue surrounding the pore becomes agitated, the pores may appear larger. Pore Epidermis Dermis Hair Hair grows out of the pores and is composed of dead cells filled with keratin proteins. At the base of each hair is a bulb-like follicle that divides to produce new cells. The follicle is nourished by tiny blood vessels and glands. Hair prevents heat loss and helps protect the epidermis from minor abrasions and exposure to the sun’s rays. Hair follicle Epidermis Dermis Sebaceous Glands Sebaceous glands are usually connected to hair follicles and secrete sebum to help lubricate the follicle as it grows. Sebum also contributes to the lipids and fatty acids within the moisture barrier. Oil production within the sebaceous gland is regulated by androgen levels (hormones such as testosterone). Sebaceous gland Epidermis Dermis Sweat Glands Sweat glands are long, coiled, hollow tubes of cells. The coiled section is where sweat is produced, and the long portion is a duct that connects the gland to the pore opening on the skin's surface. Perspiration excreted by the sweat glands helps cool the body, hydrate the skin, eliminate some toxins (i.e., salt), and maintain the acid mantle. Sweat gland Epidermis Dermis Review Dermis • Major components of the dermis are surrounded by gel-like, moisture-binding glycosaminoglycans. • Collagen is a structural protein within the dermis that gives skin strength and flexibility. • Elastin is a coil-like structural protein that gives skin the ability to return to its original shape after being stretched. • Both collagen and elastin are produced in the fibroblasts. Review Epidermis • In the deepest layer (stratum basale), new keratinocytes are formed by cell division. Melanocytes are also present in this layer. • In the third layer (stratum granulosum), keratinocytes begin to fill with the tough protein keratin. Also in this layer, keratinocytes begin to die. • In the outermost layer (stratum corneum), keratinocytes are surrounded by lipids and fatty acids, making up the moisture barrier. • The acidic area of the moisture barrier is referred to as the acid mantle. Maintain the Beauty of Skin Maintain the Beauty of Skin Beautiful, healthy skin is determined by the healthy structure and proper function of components within the skin. To maintain beautiful skin, and slow the rate at which it ages, the structures and functions of the skin must be supplemented and protected. Maintain the Beauty of Skin Soft, supple skin: Maintain the moisture barrier and acid mantle. Flexibility, elasticity, firmness: Protect collagen and elastin levels. Radiant, youthful complexion: Promote healthy cell renewal and guard against free radical damage. Translucent, luminous tone: Avoid UV damage and other causes of discoloration. Maintain healthy cell renewal. Smooth, even texture: Maintain healthy cell renewal and frequently refinish and exfoliate. Keep pores clear. Promote healthy cell repair. Test Your Knowledge Congratulations! You have completed the Skin Anatomy and Physiology Advanced Course.