ornithopoda: successful bipedal herbivores

advertisement

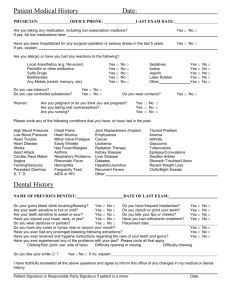

DUCK-BILLS AND THEIR KIN World of Dinosaurs Lecture 13 February 26, 2009 ORNITHOPODA: SUCCESSFUL BIPEDAL HERBIVORES - Ornithopod, or "bird foot" dinosaurs, were a clade of (mostly) bipedal herbivorous dinosaurs that existed from the Early Jurassic to the Late Cretaceous. They spanned the globe, with fossil remains recovered from every continent, including Antarctica. They ranged from small-bodied forms about 3 feet long, to true giants more than 60 feet long. - In contrast to most ornithischians, they had virtually no armor or horns of any kind. - Overall, ornithopods were extremely successful, the most successful of the herbivorous dinosaurs. ORNITHOPOD ANATOMY AND DIVERSITY - Ornithopods share a number of features. For example, the jaw joint is below the level of the tooth row, allowing the upper and lower jaws to come together like nutcrackers instead of like scissors. They have a variety of dental specializations, culminating in the extremely specialized dental battery of hadrosaurs adapted for crushing plant food. - Ornithopods can be divided into a number of groups, or clades. - Heterodontosaurids were all small-bodied, some less than a meter in length, with relatively long arms. Other distinctive features include well-developed teeth up front in the premaxilla, tusk-like canine teeth behind these, and closely packed cheek teeth forming a dental battery at the rear. They are known only from the Early Jurassic, and thus represent the most primitive radiation of ornithopods. - Hypsilophodontids were slightly larger, about 2 meters long, but still lightly built. They were common from Middle Jurassic to the Late Cretaceous, and were the first clade of ornithopods to disperse worldwide. They retained the premaxilla teeth up front and had chisel-like cheek teeth. Together, the heterodontosaurids and hypsilophodontids represent the primitive condition for ornithopods, being small, lightly built, fast herbivores with narrow snouts for selective feeding in the undergrowth. - Dryosaurids were another successful group. Most were relatively small-bodied and fleet-footed, though some exceeded 200 pounds. The dryosaurs were the last ornithopod group to have relatively short arms, preventing them from moving on all fours. - Camptosaurids were even larger bodied, with relatively longer arms, suggesting that quadrupedal locomotion was possible. They have elongated muzzles, and two functional rows of teeth in each jaw. They are known from N. America to Australia. - Iguanodontids were also generally large-bodied with long arms. They include the first named dinosaur, Iguanodon, which has been recovered from massive bonebeds including dozens to hundreds of skeletons. Lecture 13—Duck-Bills and Their Kin—1 - Hadrosaurids were the most specialized ornithopods. They are all large-bodied, the largest approaching the sauropods in size. Many species were likely quadrupedal when walking, and bipedal when moving quickly. All have relatively long skulls and many have expanded, duck-like bills. Hadrosaurs are divided into two main groups or families: crested and non-crested. The non-crested forms, or hadrosaurines, lack the development of the nasal into a tube shape whereas crested forms, or lambeosaurines, developed strange growths ranging from a simple crown to a long hollow tube projecting behind the skull. - Hadrosaurs all have highly specialized dental batteries with multiple rows of closely packed teeth that formed a continuous surface for crushing and grinding food. This was the most derived chewing system that evolved among dinosaurs. ORNITHOPOD PHYLOGENY Ornithopoda Heterodontosauridae (e.g., Heterodontosaurus) Euornithopoda Hypsilophodontidae (e.g., Hypsilophodon, Orodromeus) Iguanodontia Tenontosaurus Dryosauridae (e.g., Dryosaurus) Camptosauridae (e.g., Camptosaurus, Muttaburrasaurus) Iguanodontoidea Iguanodontidae (e.g., Iguanodon, Ouranosaurus) Hadrosauridae Hadrosaurinae (e.g., Edmontosaurus, Maiasaura) Lambeosaurinae (e.g. Lambeosaurus, Parasaurolophus) Lecture 13—Duck-Bills and Their Kin—2 - - - - - - - - ORNITHOPOD PALEOBIOLOGY AND PALEOECOLOGY Ornithopods were extremely successful, exploiting a wide variety of habitats ranging from Alaska to Seymour Island in Antarctica. It is possible to see several major evolutionary trends within ornithopods. There is a dramatic increase in body size through the lineage. The snout becomes progressively longer and broader, and becomes toothless up front. This allowed more derived ornithopods to gather more vegetation with each mouthful, and to reach deeper into the vegetation. There is an increase in the number of cheek teeth, associated with more efficient grinding and slicing. Early ornithopods have just one row of teeth in each jaw, whereas hadrosaurs had three interlocking rows in their jaws, forming a grinding battery. Thus the beak of iguanodontoids (hadrosaurs and iguanodontids) would have primarily cropped vegetation. The well-developed dental battery would then have been responsible for grinding up the plant matter prior to ingestion. Hadrosaurs had a unique, elaborate chewing system in which the upper jaws may have rotated sideways and upward somewhat to facilitate the grinding of food. Another major change was expansion of the bones in the nasal region, seen in some iguanodonts and in hadrosaurs. In these derived groups, the premaxilla and nasal bones extended far backward over the nasal opening, sometimes reaching to the back of the skull. This may reflect modifications associated with both visual display and with vocalizations. The forelimbs became progressively longer, allowing the later, more specialized forms to become quadrupedal much of the time. The hands also show modifications toward reducing the outer digits and becoming more robust. The hands of smallbodied ornithopods such as hypsilophodontids were quite dexterous, suggesting that they were used for grasping and likely aided in feeding. In contrast, more advanced, larger bodied forms like hadrosaurs had greatly reduced first and fifth fingers, and the remaining fingers changed from claw-like to hoof-like. This is an indication that the hand was used primarily for weight bearing. The relative brain size apparently increased, as measuring by the volume of the bony cavity that surrounded the brain. Ornithopods had the largest relative brain size of all ornithischians. This may relate to their reliance on acute senses for protection, rather than armor or weaponry, and perhaps also to complex behaviors. The wild headgear of hadrosaurs has led to a wide variety of hypotheses. These range from snorkels and an improved sense of smell, to weapons and display structures. Importantly, as with ceratopsids, these ornamentations are species-specific and tend to blossom late in life, both of which support the display hypothesis. There is some evidence that hadrosaurs, at least, nested in colonies, as birds do today, and that they returned to the same site season after season. Some investigators suggest that parents took care of their young for several months after hatching. Evidence for the latter includes hatchling fossils found within the nest amidst eggshell fragments. The presence of mass deaths, combined with the presence of crests, suggests that at least some hadrosaurs lived in large herds organized into dominance hierarchies. Lecture 13—Duck-Bills and Their Kin—3