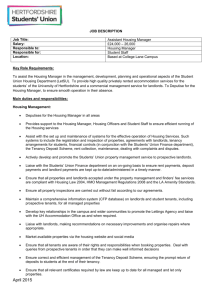

GOOD PRACTICE IN HOUSING MANAGEMENT: CASE STUDIES

advertisement