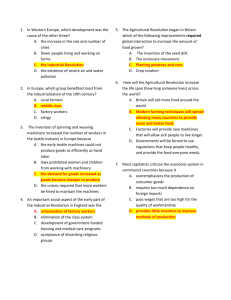

Chapter 5: The Industrial Revolution

advertisement