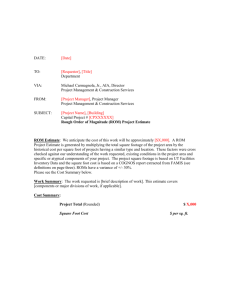

Outsourcing, managing, supervising, and regulating private military

advertisement