Final Report: A Comprehensive Assessment of Florida Virtual School

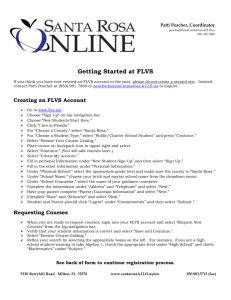

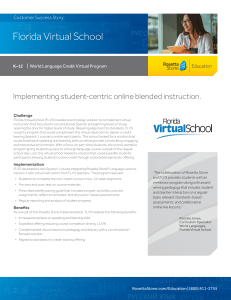

advertisement