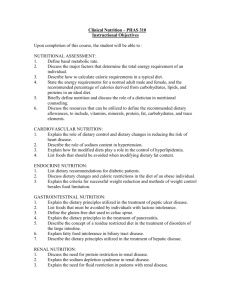

Guidelines for Dietary Planning

advertisement