doc - South Seattle College

advertisement

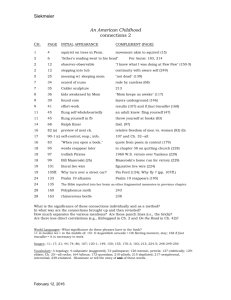

COOPER SCHOOL ORAL HISTORY PROJECT EDITED DRAFT Thelma Thornquist Audiotape [This is an interview with Thelma Thornquist on May 3, 2004. The interviewer is Judy Bentley. The other voice is Ron Thornquist, son of Thelma Thornquist. The transcriber is Jolene Bernhard.] JB: Judy Bentley TT: Thelma Thornquist RT: Ron Thornquist, son JB: This is Judy Bentley and I’m interviewing Thelma. [Tape cuts out] JB: OK, I’m going to start over. Today is May 3, 2004. This is Judy Bentley and I’m interviewing Thelma Thornquist for the Old Cooper School Oral History Project. [Tape cuts out again and resumes] JB: You were telling me about an experience of your sister coming home from school. TT: Well, the girl that died. She got halfway home and she couldn’t walk any further. There was a house that she knew the neighbors. So, she went in there and knocked on the door. They let her in and that was the end of her. She died right there. The people where she was laying sick got on the telephone and called around. They wanted to find where my mother was. JB: This was your sister. TT: My sister. She was eleven on that day. Fourteenth of October was her birthday. These people called around and they finally got a hold of my mother. My mother was walking up in the hills there. JB: Is that Pigeon Hill? RT: Yes. Twenty-Second. JB: On Twenty-Second? 1 TT: Yes, Twenty-Second. They got her and then my father was in Alaska fishing. He was a fisherman, a commercial fisherman. They tried to get a hold of him and they finally got message that someone in the home is dead. Come home. It took him ten days to come from Alaska to Seattle because of the transportation. There were no airplanes or anything. He had to just go from fishing boat to fishing boat, and work his way out down to Seattle. When he got to Seattle, of course, my sister was gone. He got on the first step to go—do you want all this kind of information?—the first step to go into the house and he just collapsed. He just cried. RT: He didn’t know who died. That’s the whole story. It makes me cry, mom tells it. One of the boys I think saw him down at the step and came down, and then he found out Ruthie had died. That’s the whole story. JB: What year was that? TT: How old was my dad? RT: No, no. What year was that, Mama? TT: Ruth was fourteen on that day—she was eleven. RT: Ruthie was born in 1906? Yes, 1906, same as Dad. She was eleven. So, that was 1917. TT: Yes, I think it was. RT: Nineteen seventeen. JB: What did she die of? RT: Our guess is a brain aneurysm. We think that’s probably what happened. JB: You were telling me before we started the tape that the nurse at the school had sent her home? Or the teacher had sent her home? TT: No. She was eleven and my brother next to her was nine. And then five and I was three. The other one was just born. RT: Did the nurse send her home or was it just a schoolteacher? Do you know that? TT: No, no. RT: Do you remember if they had a nurse at Youngstown? TT: No. Unbelievable to me, my brother, before he passed away, he said that they took my sister—the corpse—and had it in front of the window for days. He was so broken up I guess. I don’t know if he would let them take the body. He wanted to see Ruth and be close to Ruth. We 2 had two windows there in the front of the house. He insisted that they put Ruth there. Of course, she was embalmed. [Tape cuts out] JB: Can you tell me what Youngstown School was like when you went there? TT: Eleven, nine, and five, they all went to Youngstown School. Then my sister that was two years younger. We were all two years apart. RT: What do you remember about the school? You were telling me about the school one time and you remember some things. You remember some of your teacher’s names. TT: Oh, yes. Miss [Florine] Bassett was in the second or fourth grade. Miss Bassett. I know all three of us—my brother, my sister that is dead now, and me—we all had one teacher. Miss Bassett. Then we all had Miss [Gloria] Hackett. I think she was about in the fifth grade. We were still going in the old building but just that year, I think it was that year, they built the new— RT: The addition. TT: Yes. Addition. We were so thrilled because we were going to get to go into the new building. JB: Were you in the old wooden-framed building at first? TT: Yes. It was just a wooden-framed building. JB: Is this what it looked like? [showing Thelma a picture] TT: That’s it, yes. Up above was the fifth grade and down below was the third grade. There was no cafeteria. I don’t think there was even a drinking fountain in the hallway! I don’t think so. JB: Did you bring your lunch then? TT: What? JB: Did you bring lunch with you? TT: Oh, yes. My mother made four lunches that morning. We all took ours because we had to stay the whole day. It was nothing unusual. It was just what we did. All the other children did. There was no serving of anything. But we were happy and content. We never fussed about anything. JB: What was the new addition school like? When you got the new school? Was it a lot bigger? 3 TT: Oh, yes. That was stairs, so we could go up one flight of stairs. We were thrilled with the new building. I think it was finished in 1917. JB: Yes. TT: Yes. We were so glad we were going next year into the new building. We just had that playground there. It was rocks or gravel. There were a couple swings there. I think there were four swings there that we had. It might have been only two... but, as a matter of fact, it was four. The principal was on the first floor and—Miss Bassett? It’s just too bad this wasn’t two months ago when my brother was alive. He just passed away. He had such a sharp memory because he lived in Seattle in the same house practically fifty years. RT: You have a good memory, too, Mom. JB: You’re doing fine. Tell me a little bit about the house that you lived in. TT: That we lived in? JB: Um-hmm. RT: [introducing man who walks into the room] This is Jim, my younger brother. [Tape cuts out] RT: She wants to know about the house, Mom. TT: My mother and father were married in 1906 in Seattle. We were all born in that front room. Do you know what a front room is? We weren’t allowed to go in there, the front room. They had a stove that, when there was company, my mother had to build a fire. Kind of a potbellied stove type. So warm because it was cold. We had four rooms on the first floor. A kitchen and an addition for chairs for breakfast. Then the front room. And then another dining room and a utility room where we walked upstairs. There was a railing and stairs that we could walk up. JB: Now, this was the house on Twenty-Second? TT: Twenty-Second, uh-huh. RT: What’s the address, Mom? TT: What? RT: The address? You remember the address. TT: Oh, yes. Thirty Eight Thirty Twenty-Second Southwest. There was no zip code then. 4 JB: You were born in that house? RT: Literally. JB: In what year were you born? TT: I was born [19]12. Nineteen twelve. My mother had the five children all in the dining room, where there was a couch. A leather couch. RT: Where the doctor delivered the babies? TT: Yes. The bathroom, we didn’t have a bathroom but we had water in the house. We had a tub, just a washtub where you could take a bath once a week. Out, there was about six, eight steps—there was a chicken coop. My mother was interested in a chicken coop because she baked cakes a lot. JB: She needed the eggs. TT: So, we had the chicken coop there. Just beyond that ten feet was the toilet. Outhouse. JB: Were there many people around you? What was the neighborhood like? TT: Yes. Next door, they built after we had established. My mother and father bought the house practically when they were married. My mother was a Salvation Army officer in the East. In Chicago, Minneapolis. My father happened to come into the meetings where she was holding the— RT: Mom, you’re telling stories of Chicago. Grandma and Grandpa. JB: [smiling] Bring them back to Seattle. RT: Exactly, you need to bring them back to Seattle. They came back and got married in Seattle. TT: They wrote letters for seven years back and forth. They were married here in Seattle. Then she gave up the Army and my dad went to Alaska—I thought it was every two months but it might not have been that much. RT: And they had a boat dock. He could walk off the hill right down where he parked his boat. JB: On the north side or on the east side? RT: Right where ATL [shipping line] is. Like where Chelan Cafe is. A little bit towards town, go there, and it’s all industrial now. That used to be an area where you could keep your boats. 5 Commercial boats, small boats. He kept the Velero there. He would dock it there, and then he could just walk up the hill and he was home. JB: The name of it was the Velero? RT: The Velero. [Judy tries to spell it] RT: V-E-L-E-R-O. That was the Velero. And that was his boat. JB: He had his own commercial boat. RT: [chuckling] It wasn’t much. Forty-two footer, two men. Two men fit. JB: But he fished in Alaska. RT: He fished halibut. That was his occupation. JB: Who were the other people in the neighborhood? TT: Next door to us was Hammonds. They had been married, so they had one child when they moved in there. Next to them were Dears [sp. uncertain], downhill north. There was an old mother and a young couple lived there. Dears. Then the next house— Are you interested in anything of this? JB: Not so much the names as what kind of work they did and what kind of families they were. TT: Nine-tenths of them worked in the steel mill because that was so big. World War II, they used so much steel. Across the street was— RT: The Greeks. TT: Was one family. They were Greek. They came from Greece. The boy, his name was August, and their family name was Alexander. They more or less kept to themselves because she never learned to speak any American. The boy, he went to the university. The father bought the first fish market on Railroad Avenue. It was Railroad Avenue then [Alaskan Way now]. JB: Downtown. TT: Yes. So, the boy was managing that for awhile, while he went to school. They had a little girl also. About ten, twelve years difference in the ages of the two. Maybe Alexander was born in Greece, I don’t know. But they all spoke Greek. RT: The majority of the hill spoke Scandinavian, Swedish. I don’t know if you’re aware of that. 6 JB: Yes but you can tell me more about that. Was your family Scandinavian? RT: They spoke Swedish in the home. Mother still can speak perfect Swedish. [speaking to Thelma] You said when you started school, you spoke better Swedish than you did English. [Thelma can’t understand what he says for a moment] TT: Oh. Yes. RT: And you could speak Swedish up on the hill to the kids. TT: My father was gone for two months at a spell and then come home. Mother, she never went to any school in this country. JB: Was she an immigrant? TT: My mother. She was seventeen when she left Sweden. RT: Her father was an immigrant also. TT: That whole family, there were nine girls and one boy. My mother’s family that left Sweden. They settled in Minnesota. RT: That’s a long story, Mother. A lot of people called it Goat Hill way back then. They called it Goat Hill. Didn’t they, Mom? Now they call it Pigeon Hill. JB: Pigeon Point. RT: Pigeon Point, which is a little more sophisticated but I thought they called it Goat Hill back there, too. Didn’t they call it Goat Hill? [repeating himself so Thelma can hear] Didn’t they call your neighborhood Goat Hill? [Thelma doesn’t answer] RT: No? I know Carol would talk about that. Did they call it Goat Hill? No? I’m sorry then. I would correct Uncle Carl or Uncle Vic because I would say, “Now it’s Pigeon Point.” But they would refer to it as Goat Hill. The four that graduated from Youngstown—two boys and two girls—the two boys when they graduated, they had to go right to work. They went to the store. JB: From the eighth grade? RT: From the eighth grade, they went right to work. They had to get jobs. JB: At the steel mill, did you say? 7 RT: No, there was a stove factory down on Harbor Island, down from Riverside. Vic went there, the first one. He went there the first time. Two years later, Carl followed after he graduated from the eighth grade. He went to work in the stove factory down there kind of like by West Marginal Way. [speaking to Thelma] Where the stove factory was? TT: I guess so. East Marginal, West. I guess so. RT: This side here. And the Indian reservations were down there, too, in that area. TT: What? RT: The Indian reservations were down there. TT: I don’t know. RT: I thought you got all kinds of little things from the— TT: Oh, yes! The Indians. [teasing her son] You don’t talk plain today! JB: Tell me about what you found in the Indians. TT: There were Indians, an Indian village. A whole tribe was on the Island. They were poor, they had nothing. No money, nothing. My mother gathered clothes from the neighborhood that were cast off. My brother took a shopping bag and maybe once every two, three weeks, he would go down to the Indian village and give them the clothes. They would give him baskets that they had knitted. RT: They were weaved. We have a couple of them. They’re all broken apart. She still has them. JB: Do you know what they wove them out of? TT: I can’t. We had a dumb dog one time. That dumb dog went and got a hold of that— RT: You still have a couple of those. One’s still in good shape and one is kind of ripped up. That came from the Indians, you said, down there. You talked about them before. JB: Where were they living? Where was the village? On the island? RT: Were the Indians across on Harbor Island? TT: Yes. RT: Across on Harbor Island? TT: Yes. You had to cross that— 8 JB: You had to cross something to get there? RT: How did you get over to Harbor Island? TT: We always had a rowboat. My father had a fishing boat, we always had a rowboat. The kids just loved to go in the rowboat. So, maybe one or two or three of them would go with Carl. He was kind of scared. There was a rumor that the Indians would take you, the white people, and sell them. Like that Negro thing. That’s how he got there. They gave him these little baskets. So, they liked him. He was cheerful and kind of roly-poly. [chuckling] RT: He was a good guy. The two boys went to work. There was a stove factory down there somewhere. Stove, S-T-O-V-E. The stove factory. Uncle Vic went down there first when he graduated from the eighth grade. Two years later, Carl went down there. Then the two girls, Thelma and Esther, they couldn’t get jobs right away, so they went on to West Seattle High School. Both of them graduated from West Seattle High School. Mom was class of [19]30 and Esther was class of [19]32. That’s kind of the background there. JB: Let me go back and fill in a couple of things. Do you remember any Indian children? TT: No, no. They kept to themselves. JB: So, they didn’t go to school with you. TT: They didn’t go to school that I know of. I don’t think so. JB: How did you get to the school? TT: Just walked. From our place, it was about seven blocks. A couple were the steep hill. Andover is very steep. We just walked and had rubbers for shoes, on our shoes, because nobody had any cars then in 1917. They just walked to school. JB: Was it wooded or was it clear? Was there a clear trail that you were walking on? TT: It was just a trail. RT: Did you walk through the woods or did you walk on a street? TT: Anywhere we could. Almost the sidewalk but there were no sidewalks. Kind of path. I think the people that lived in would take some of their rocks so that the children could— JB: They created a path? TT: Yes. When we got to school, our shoes were dirty, naturally. It was a long walk. Not as for kids, it wasn’t. But my sister, when she got sick, that was a long walk. Tried to get home but she didn’t. 9 JB: What do you remember about your classes at school? The subjects that you studied in your classes? Do you remember? RT: What subjects did you take, Mom? You remember your subjects you took in class? TT: Go in that top drawer. There’s all kinds of... Ruth. RT: No, no. Just tell her what subjects you took. TT: The very day she died, she had written a... marked her good or bad. I’m going to show you that. [Tape cuts out] JB: Tell me about penmanship. TT: We’ve got some papers, a whole bunch of papers. Me and my mother were alone at home with five kids. My father was in Alaska. She kept everything, every scrap. [Tape cuts again] TT: The card tables that we got in the— JB: Do you remember having recess or playing outside during school days? TT: I don’t think there was anything like that at all. I think the kids had a pair of scissors, and they could cut the holes and make designs. Then they would paint over those designs and they would have a picture. You know, they had no money for anything. Nothing. Maybe the school was in a poorer district. It was definitely a workman district. The streetcar would just come so far. It was down at Riverside and then it went back. The children didn’t have any privileges like that at all. JB: So, there wasn’t a lot of art or music in school? TT: No, no. JB: Just reading and writing and math? TT: Yes. Music. [pause as Thelma thinks] The boys pounded nails in boards. They made sleds. JB: Oh, really? At school or at home? TT: I think at home because the school didn’t supply them with anything. They were very awfully good kids. 10 JB: The children got along with each other at school? TT: Yes. Definitely. We respected the teachers and the principal. If you had to go to the principal, you knew you were going to go there. We just respected them. It was a natural thing. JB: Did you ever have to go to the principal? TT: No. That was what we heard. RT: Did you ever go to the principal, Mom? TT: No. JB: Do you remember your eighth grade graduation? TT: I was in the third grade. RT: Do you remember your graduation at the eighth grade? When you graduated? TT: Oh, the eighth grade. RT: Your graduation. You got your graduation picture. TT: But that was in high school. RT: No, no. I mean the one they took on the steps there. JB: At the end of eighth grade, they usually take a picture. RT: Class picture. TT: Yes. RT: You remember, did they have some kind of graduation? TT: I think the last day of school—it was billed as the last day of school—the kids were so happy. Maybe we got cookies but I can’t remember that we ever got anything. I don’t remember that we got anything. It was a working man’s section of the town. We were lucky that the streetcar went to Andover. Then it stopped and that was the end of our riding. I know my mother used to go down to the market every Saturday. JB: The Pike Place Market? TT: Yes. There were no stores, supermarket or anything like that. 11 JB: In your neighborhood? There were no stores in your neighborhood? TT: No. END OF AUDIOTAPE, SIDE A TT: I’m sure she planted carrots and potatoes in the backyard. Other than that, no one brought anything around. There was a man who had a wagon. He put a tin pail in it and he built a fire in there. He had a sheet, around working there. He had a sheet over that. I know my mother, once a year, had to have her coffee pot tinned. RT: Copper tinned. Replated. Those were the Gypsies. Weren’t they, Mom? That came, that did the replating. JB: The man with the wagon, was he a Gypsy? TT: Yes, he was a Gypsy. JB: He brought that wagon around once a year? TT: Yes, then knocked on the doors of the house, if they wanted anything retinned. Because there was no other way, just to throw it away. They couldn’t afford to throw it away. One funny incident, my mother answered the door and the Gypsy asked if we wanted anything tinned. My mother wanted her coffee pot retinned, so he went to his wagon down below. We were about twelve, fourteen steps up off of the road. My sister and I—my sister’s two years younger than I—we stood and pulled apart the curtain and watched what was going on. Pretty soon he was going to come back up and get his money, and bring the [coffee pot back]. Well, we had heard that Gypsies take the white girls and sell them. We were scared to death. We were hiding under the bed when he was out there. Then we got to go back out. Oh, we were scared of those Gypsies. They were in their costumes, too. RT: Dressed like Gypsies. JB: Do you remember what that was? What that looked like? How were they dressed? TT: The bright color of the scarves and the skirts. They wanted you to know who they were also. JB: Were there women with them? Were there women, too? TT: I don’t know. It usually was the men that had to build the fire and watch the fire. Anybody that had to have anything welded—there was no place to go to fix a, maybe a horse’s... JB: Hoof? Shoe? 12 TT: The harness or whatever. JB: How long did you live in that house? TT: Twenty-one years. Didn’t we, Ronnie? RT: When you were married, you were in that house. Grandma and Grandpa passed away in [19]41. Then you sold it in [19]41. TT: I was still living there at that time. RT: Even when I was born, you brought me home to that house. We moved shortly thereafter. TT: It was a nice house because it was brand new when we moved in there. Practically. It was a nice house, a big house. The rooms upstairs were very big. Two in each room, the kids. JB: Who built it? Do you know who built it? TT: I can’t say who built it. I’ve got a deed from that house, when they bought it. The city gave them a deed. I have that but I don’t know who actually built it. JB: Your parents didn’t build it then? RT: No, they didn’t. An interesting story, the Depression, when the hoboes made a mark on Grandma’s—I had read about that. They had a bulkhead. They had a concrete bulkhead. I think? Yes, they had a concrete bulkhead. The hoboes, where they would go—and the railroads were there, of course—they would try to find out where they could get a meal or if somebody would give them something to eat. If they found a place where somebody would give them something to eat, they would make a mark somewhere where they would let a hobo know you could get something. Grandma was very, very goodhearted. You’ve told this story many times. There was a mark on your bulkhead. When they came up to get something to eat, Grandma always made them go to the back door, you said. Do you remember that story, Mom? TT: Yes, of course. JB: How far was the bulkhead from the house? RT: The bulkhead was right there and then you went up about ten or twelve steps. Then it leveled off and you went up another ten or twelve steps to the top of the porch. Or you went around to the back. JB: The house faced towards the water? RT: The house faced directly towards Bethlehem Steel. TT: It faced west. 13 RT: Yes, due west. TT: The water was in front of us. RT: The tideflats were there, of course, before they filled them in. JB: Do you remember anything of the steel mill? What do you remember about the steel mill? RT: What do you remember about the steel mill? TT: [chuckling] Yes. It was part of our lives. Everybody on that hill worked at the steel mill. Every morning at eight o’clock, the whistle blew. It blew loud and long. Then at three o’clock in the afternoon, same whistle blew at three in the afternoon. And once in awhile, nine o’clock at night. Evidently, they were having overtime or something. JB: Two shifts. TT: Yes, then that would blow. Other than that, my [brothers] and my father, they didn’t work in the steel mill. I think it was a closed deal. They took all the men that came from the East. Well, I’m wrong there. The man next door to us, he worked in the steel mill. And three doors down, he worked. We all thought they were so lucky to get to work for them because they would always work. They got good pay and they got pay. That was Hedmans [?]. They were Swedes from Sweden. They had their [?] on ours. They were from Sweden. So, it was an awful lot of Scandinavians on that hill. Practically exclusively. RT: The Swedes. Some Norwegian. Mostly Swedes. JB: Then down in the valley, I’ve heard there were more Italians living there. TT: They were Italian, all. Yes. There was no question about that. They held themselves to a certain degree. They didn’t mix with us. We didn’t have the money that they had. They had more money because the steel mill paid every week, where the fishermen—my father—when he got the load, and came down and sold it. RT: They had good looking boys, those Italian boys, Mom. [teasing her] The Italian boys were good looking. [Thelma chuckles] JB: In school did you mix, the Italians and the Swedes? When you were in school together did people still stay apart? TT: Well, no. We played together, more or less. We didn’t ostracize anybody, anyone. We more or less played with those three or four. The recess time wasn’t that long. We’d just get to go out and get some fresh air. Then we had to come back in. We didn’t have any trouble with 14 them. Not at all. Some of my best girlfriends were Italian. They were small and they were pretty. JB: Do you remember any strikes at the steel mill? TT: The strike? JB: Yes, were there any strikes? TT: There probably were but that didn’t interest me. Later on during the war, the second World War, then there were strikes. But not the first World War. My mother, she used to try to plant a little garden. Have some carrots because they figured the kids need vegetables. That didn’t work but my mother took her shopping bag and one of us kids with her to the public market once a week. We got to ride the streetcar. JB: The streetcar? TT: Yes. RT: They went to the public market every week. Mother, even when I was a little baby, you still had a habit of going to the public market. You call it the streetcar—you’d take the bus and you’d go to the public market for a long time. TT: Yes. RT: Mom stayed up on the hill for awhile until they moved up here later on. They were in the Youngstown area for— JB: For quite awhile. TT: Once a month, they had a streetcar sale, they called it. You walked into the streetcar, maybe had three bundles and an umbrella—well, you had to hurry to get off the streetcar because he wasn’t going to stop that long for you. So, we forgot her umbrella. About once a month or once every six weeks, they had a... RT: Lost and found, Mom. Lost and found. JB: A sale of things in the lost and found. TT: Yes. You got a whole shopping bag full of some kind of shoes for one dollar. I’ll never forgot—Mama got a brand new pair of shoes, boy’s shoes! Who needed shoes? I had to wear boy’s shoes to school. That was a hard thing to do. JB: To wear boy’s shoes to school? TT: Yes, yes. 15 RT: When Grandma gave her the shoes, Mom says she cried because she didn’t want to wear the boy’s shoes. But, finally, she had to. JB: Did the other children make fun of you or not? Did they tease you about the shoes? TT: Well, not really. They were too busy with their own. But they mentioned it: “Thelma’s got boy’s shoes.” JB: Did you ever hear about or were you part of something called the Youngstown Improvement Club? TT: The what? JB: The Youngstown Improvement Club. TT: No, I’ve never heard that until just a couple years ago. A lady asked me something about it. We were content to get the meager that we did get, from the counselor or whoever deals out the money. We didn’t get any pension, no. RT: They had a reunion about, what, six to eight years ago? Maybe ten years ago. JB: I heard about that RT: Yes. Mom went, and the two brothers were allowed. They went, too. That’s in one of the pictures. TT: What? RT: Your reunion. When you had a reunion for some of the oldtimers. Remember you went to the Youngstown reunion? [pause as Thelma thinks] RT: You went to the Youngstown School reunion about ten years. You remember. Carl went and Vic went. TT: Yes, but we didn’t figure that we were a part of them. JB: A part of? TT: Of the Improvement Club. When you get ninety years old, you don’t bother about reunions. [laughing softly] 16 JB: Let me show you a couple more pictures. See if they are anything that you remember. I don’t know that they will be. These are some pictures from the neighborhood and from the school early on. RT: Ohhh! Isn’t that sweet? JB: I got these from the school district archives. This is a picture of two boys on a horse delivering newspapers. And this is a picture of exercises in the schoolyard. Doing exercises. Do either of those pictures look familiar or no? TT: That looks familiar. The exercises. I don’t think that more than once a week we got an exercise period. Then we had to stand there. JB: Did a teacher lead those exercises? TT: I don’t know. But that’s what that was. [handing the picture to her son] Want to see the exercises? JB: These are pictures from school, too. TT: Oh, yes. JB: This is one about signing the Declaration of Independence. RT: Nineteen twenty-three. JB: Yes, 1923. You would have been in school then. RT: Yes. Those are some of your classmates, Mom. JB: Dressed up as Thomas Jefferson and... TT: There were Fitzgeralds in the school. There was a famous artist? JB: That’s what it says. TT: That’s interesting. JB: This one is sometime before 1929. This is an observance of Book Week. It was a pageant. RT: Mom was in high school then. You’ve seen her graduation picture, I would imagine. [Tape cuts out as son goes to retrieve picture] JB: This is your eighth grade graduation picture? Is that right? 17 TT: Uh-huh. That’s the whole class. JB: And your dresses... TT: I think we made our dresses in school. JB: That’s what I’ve heard from other people. Where are you? RT: She’s the prettiest one! Look at that. [The women chuckle] RT: She’s the prettiest one. JB: Right there. RT: Isn’t she? JB: Uh-huh. Very pretty. RT: You bet. JB: One of the tallest ones, too. TT: I know the names of nine-tenths of them still after all of these years. JB: What kinds of last names? Just give me some of the last names. TT: Well. This is about in 19— RT: Name some of the names. TT: Twenty-six. That’s good. That’s [19]26. RT: Yes, she would have been fourteen. [Tape cuts out, then resumes] JB: This is another picture of kids kind of grouped in front of—is this the school here, the new part of the school? TT: That’s the school, yes. JB: With the bricks. That’s the new part? 18 TT: That’s the brick. And there’s the cement for us to walk on. There I am up there. JB: Do you know some of these kids? TT: Oh, I know them all. That’s Maria. Helen Wills. [sp.?] JB: Helen Wills? TT: Yes. That’s the Greek that lived across the street from us. JB: Alexander was his last name? TT: Uh-huh. Alexander. JB: Was he the only Greek kid in the group then? Everybody else was Scandinavian or Swedish or Italian? TT: We never had a Greek at school. We had Irish. JB: The Fitzgeralds, maybe? TT: Well, I know that I got to ride in a canoe with two other girls. And we were supposed to be Irish. It was in the front page of the Times or whatever. JB: A real canoe? TT: [to her son] Have you got that? JB: On the river? TT: Yeah, you got it. We were chosen, not because we were Irish, that’s for sure. RT: [calling out from another room]: Yes, you were supposed to be Irish lasses or something, Mom. It was kind of a phony picture because you weren’t an Irish lass. I don’t know where we can find that [picture from the Times]. These might be a little bit later but Mom knows all these kids. This is the gang. It’s kind of cute, the styles of the day. [Tape cuts out] JB: You say you were having some love in your heart about the school. TT: Well, we had a love because we were more or less separated. I mean we were the only school down in that district. Up on the hill and even west, there was nobody. I think maybe the closest school that had children was probably Jefferson. xxx where was that? xxx Jefferson or... it could be Jefferson. 19 JB: Haller. There was a Haller school in the early 1900s. TT: Haller? JB: Haller. In West Seattle. Children would have had to have taken the streetcar to get there. So, it was considered too expensive for the children in Youngstown. TT: Yes. JB: Is that what you’re remembering? TT: Yes. RT: We drive by Youngstown every other day, and Mother looks longingly at the school and has wonderful memories. At night, she’s worried that they’re going to knock it down. I say, “No. I think they’re going to save it. They’ll do something with it but they’ll save it.” She has an affection for it. [Tape cuts out again, then resumes] JB: You’re talking about every Saturday night, after you’d been to the church. The Salvation Army church. Go ahead. TT: Uh-huh. For twenty-five cents, we got a chunk of ice. That was our refrigerator, like milk. We didn’t bother about that, that just stood. We just loved when my brother stopped his car, and the kids got chips of ice that had fallen because they clamped [the chunks of ice] with clamps and put it in our car. Just put it in our car. We’ll never forget that. My mother, in her pantry, she had an opening about that [spreading her hands] where fresh air could come in. [spreading her hands] That was our icebox. We had an icebox but it was not, you know— JB: Filled with ice. TT: You think of what we have now. JB: Where was the Salvation Army church? TT: Where? JB: Um-hmm. TT: Occidental and Main. RT: Skid Row. Skid Row district. Although, Skid Row was a lot of good memories. JB: There was a church on Pigeon Hill? 20 RT: That’s the Salvation Army church. That’s the Youngstown corps of the Salvation Army church. TT: Across the street from that... what kind of a church was it? They had a Sunday school there. We had a Sunday school on the west side and they had it. RT: There were two churches there? TT: Yes, they had a church. They built it and it stood for maybe four, five years. That’s all. JB: When you went to church at the Salvation Army, you went downtown? TT: We had a Sunday school and youth work on Twenty-Third and Andover. RT: The building, the house that’s there right now on Twenty-Third, on the corner of TwentyThird and Andover, right on there. You know the one I’m talking about? JB: I think so. The one that became a union hall? RT: No, the union hall was across the street. Right across the street. If you look at it, this is a total private residence. This private residence was built in the 1920s by members of the Salvation Army. They built it and turned this into the Youngstown Corps. The Youngstown Corp—a long story. Up on top was the residence and down below was this great, big open basement. The open basement was where you had the Sunday schools and the Boy Scouts and the Cub Scouts and the Girl Guards. Mom was involved with that. For forty years, that was the Salvation Army Youngstown Corps. The officers that lived in that building, in that residence, during the week they had the Boy Scouts and the Girl Scouts and the Salvation Army Girl Guards, that activity. Then Sunday morning, they had Sunday school. Now, those officers—they’re called officers, ministers—those ministers that lived there, then Saturday night and Sunday night went down to what they called a corps at a church down on Skid Row. So, Mom was a part of that corps. Mom was a part of that Salvation Army corps that worked in the Youngstown building, which was just like a house with a big basement and she also went down to Skid Row, to the services down on Skid Row. TT: Can I brag just a little bit? JB: Sure! TT: Show her the— RT: No, no. TT: Let her see it! 21 RT: She’s had all kinds of awards. She’d worked for the Salvation Army for seventy years and has done so much. [Tape cuts out for the final time.] END OF INTERVIEW OF THELMA THORNQUIST ON MAY 3, 2004. 22