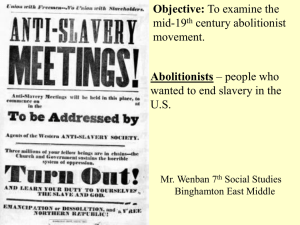

Abolitionists

advertisement

Lucy Stone (13 Aug. 1818-18 Oct. 1893), abolitionist and woman's rights activist, was born in West Brookfield, Massachusetts, the daughter of Francis Stone and Hannah Matthews, farmers. Her hard-working parents transmitted to their daughter--one of nine children--both their abolitionist commitment and their Congregationalist faith. Young Lucy retained their radical antislavery stance but found herself increasingly distant from the Congregationalist church after its leaders criticized abolitionists Sarah Moore Grimké and Angelina Emily Grimké for unfeminine behavior in speaking to mixed audiences in churches during their 1837 tour of Massachusetts. Stone also broke with her parents in pursuit of higher education. At the age of sixteen, after completing local schools, she taught and saved money for advanced study. She attended nearby Mount Holyoke Seminary for one term in 1839, returning home to attend to the illness of a sister. Stone waited until 1843 to enroll at the Oberlin Collegiate Institute (later Oberlin College); with her graduation in 1847, she became the first Massachusetts woman to earn a bachelor's degree. Confirmed in both her abolitionist and feminist beliefs during her years at Oberlin, Stone gave her first public talk on woman's rights from her brother's pulpit in Gardner, Massachusetts, in December 1847. She was then hired as an agent for the Garrisonian Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society the following year. Admonished by her employers to cease her practice of mixing the two controversial topics in the lectures they sponsored, Stone responded, "I was a woman before I was an abolitionist" (Woman's Journal, 15 Apr. 1893). She then proceeded to arrange to speak for the society on weekends, while reserving her weekdays for lectures on woman's rights. A popular orator, Stone garnered praise from William Lloyd Garrison's paper, the Liberator, for her "conversational tone. . . . She is always earnest, but never boisterous, and her manner no less than her speech is marked by a gentleness and refinement which puts prejudice to flight" (25 Aug. 1848). In addition, she played a leading role in the burgeoning woman's rights movement, serving as an organizer for its first national convention in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1850. Until 1855 Stone was in perpetual motion, lecturing across the country for feminism and abolitionism and related reforms, including temperance, dress reform, and married women's access to property rights and to divorce. Her own marriage in 1855 to Cincinnati hardware merchant Henry B. Blackwell, however, slowed her pace. A fellow abolitionist and the brother of pioneer women doctors Elizabeth Blackwell and Emily Blackwell, Henry Blackwell joined with Stone in celebrating their union with a protest against the legal inequalities of husband and wife. He also supported Stone in her decision later that year to reclaim her birth name as her legal signature. In 1856 Stone's family network was further augmented when her dear friend and Oberlin classmate, Antoinette Brown (Antoinette L. B. Blackwell), the first woman ordained in a regular Protestant denomination, married Henry Blackwell's brother Samuel Charles Blackwell. While Stone maintained visibility within the abolitionist and woman's rights conventions, she also devoted considerable energy to her husband's struggle to establish himself, first in Chicago as a publisher's representative, then in northern New Jersey, and to her only child, Alice Stone Blackwell, who was born in 1857. Despite her family responsibilities, Stone nonetheless protested her disfranchisement in 1858 by allowing the seizure of her household goods at her Orange, New Jersey, home rather than pay taxes levied by a government in which she could not participate. During the Civil War, Stone joined other feminist-abolitionists to found the Woman's National Loyal League, an organization committed to the full emancipation and enfranchisement of African Americans. When Reconstruction began, Stone became a founder of the American Equal Rights Association (AERA), a union of woman's rights and abolition supporters determined to support the extension of voting rights irrespective of both race and sex. Under its auspices, Stone made an extended tour of Kansas in 1867, campaigning for state constitutional recognition of equal rights for both women and African Americans. But federal congressional action, first on the Fourteenth Amendment, which provided civil rights for freed slaves while ensuring voter protection only for men, and then on the Fifteenth Amendment, which guaranteed equal rights without regard to color while pointedly neglecting the issue of sex, angered many woman's rights supporters. Stone ultimately resigned herself to the provision of voting rights for African-American men without concomitant enfranchisement of white or black women. Declaring "I will be thankful in my soul if any body can get out of the terrible pit" quoted in Elizabeth Cady Stanton et al., eds., History of Woman Suffrage, vol. 2 [1881], p. 384), she continued to support the Republican party. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton felt differently, and in May 1869 they led an exodus from the AERA to form the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). The new organization refused to support constitutional changes that did not at the same time enfranchise women. Later that year, Stone, her husband, Mary Livermore, Julia Ward Howe, and others held a convention in Cleveland, at which they founded the rival American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) dedicated to achieving woman suffrage, especially through state-level legislation, while refusing to undermine achievements in African-American civil rights. Also in 1867, Stone and Blackwell relocated their household to Dorchester, Massachusetts, and raised capital for a newspaper to be called the Woman's Journal by selling shares in a joint stock company to Boston supporters. Livermore agreed to merge her Chicago-based reform paper, The Agitator, into the new publication, now issued from the Boston headquarters of the American Woman Suffrage Association, and remained editor in chief from the debut of the paper on 1 January 1870 until 1872, when Stone assumed primary responsibility for the weekly appearance of this official organ of the AWSA with assistance from her husband and, after 1882, their daughter, Alice. Stone remained in demand as a suffrage speaker, addressing state legislatures, women's clubs, collegiate alumnae, and political conventions from Colorado to Vermont, but increasingly she focused her attention on the paper, which she likened to "a big baby which never grew up, and always had to be fed." "Devoted to the interests of woman, to her educational, industrial, legal and political equality, and especially to her right of suffrage," the Woman's Journal, and particularly Stone's writing, covered a vast array of events, history, and personalities. Ironically, Stone's principles blocked her one attempt to exercise her own right to suffrage; in 1879 she registered under the new Massachusetts law permitting women to vote in school elections, but her name was erased by officials who refused to accept her enrollment under her own, not her husband's, surname. For many years, Stone maintained a virulent (and reciprocated) animosity toward Stanton, Anthony, and the NWSA, yet she ultimately became convinced that reunification of the suffrage movement was in the best interest of all. In 1890 she assisted the merger of the NWSA and the AWSA into the National American Woman Suffrage Association, becoming the chair of its executive committee, but her failing health kept her close to home except for occasions that honored her pioneering suffrage activism. Her last public appearance took her to the Congress of Representative Women at the Chicago World's Columbian Exposition in May 1893. After she died at her home in Dorchester, Stone's was the first body cremated in New England. Lucy Stone was a key figure in the American woman's rights movement for nearly a half century, bringing it from tutelage within the abolitionist movement to full organizational autonomy. Firmly committed to natural rights irrespective of sex, Stone maintained a distance from more controversial gender issues, such as divorce and free love. Instead, she worked tirelessly as lecturer, organizer, publisher, and tactician in pursuit of full legal equality, particularly the enfranchisement of women. Abby Kimber The question of woman's right to speak, vote, and serve on committees. . .disturbed the peace of the World's Anti-Slavery Convention, held [in 1840] in London. The call for that Convention invited delegates from all Anti-Slavery organizations. Accordingly several American societies saw fit to send women, as delegates, to represent them in that august assembly. But after going three thousand miles to attend a World's Convention, it was discovered that women formed no part of the constituent elements of the moral world. In summoning the friends of the slave from all parts of the two hemispheres to meet in London, John Bull never dreamed that woman, too, would answer to his call. Imagine then the commotion in the conservative anti-slavery circles in England, when it was known that half a dozen of those terrible women who had spoken to promiscuous assemblies, voted on men and measures, prayed and petitioned against slavery, women who had been mobbed, ridiculed by the press, and denounced by the pulpit who had been the cause of setting all American Abolitionists by the ears, and split their ranks asunder, were on their way to England. The fears of these formidable and belligerent women must have been somewhat appeased when Lucretia Mott, Sarah Pugh, Abby Kimber, Elizabeth Neal, Mary Grew, of Philadelphia, in modest Quaker costume, Ann Green Phillips, Emily Winslow, and Abby Southwick, of Boston, all women of refinement and education, and several, still in their twenties, landed at last on the soil of Great Britain. Many who had awaited their coming with much trepidation, gave a sigh of relief, on being introduced to Lucretia Mott, learning that she represented the most dangerous elements in the delegation. The American clergymen who had landed a few days before, had been busily engaged in fanning the English prejudices into active hostility against the admission of these women to the Convention. In every circle of Abolitionists this was the theme, and the discussion grew more bitter, personal, and exasperating every hour. The 12th of June dawned bright and beautiful on these discordant elements, and at an early hour anti-slavery delegates from different countries wended their way through the crooked streets of London to Freemason's Hall. Entering the vestibule, little groups might be seen gathered here and there, earnestly discussing the best disposition to make of these women delegates from America. The excitement and vehemence of protest and denunciation could not have been greater, if the news had come that the French were about to invade England. In vain these obdurate women had been conjured to withhold their credentials, and not thrust a question that must produce such discord on the Convention. Lucretia Mott, in her calm, firm manner, insisted that the delegates had no discretionary power in the proposed action, and the responsibility of accepting or rejecting them must rest on the Convention. At eleven o'clock, the spacious Hall being filled, the Convention was called to order. [The American abolitionist Wendell Phillips immediately made a motion to admit the female delegates to the Convention, setting off hours of vociferous debate. Ultimately, a large majority of the Convention's male delegates voted to exclude the women formal participation in the meeting, insisting instead that if they wanted to attend, they could listen to the proceedings from behind a curtained wall]. . . . However, the debates in the Convention had the effect of rousing English minds to thought on the tyranny of sex, and American minds to the importance of some definite action toward women's emancipation. As Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton wended their way arm in arm down Great Queen Street that night, reviewing the exciting scenes of the day, they agreed to hold a woman's rights convention on their return to America, as the men to whom they had just listened had manifested their great need of some education on that question. Thus a missionary work for the emancipation of woman in "the land of the free and the home of the brave" was then and there inaugurated. As the ladies were not allowed to speak in the Convention, they kept up a brisk fire morning, noon, and night at their hotel on the unfortunate gentlemen who were domiciled at the same house. Mr. Birney, with his luggage, promptly withdrew after the first encounter, to some more congenial haven of rest, while the Rev. Nathaniel Colver, from Boston, who always fortified himself with six eggs well beaten in a large bowl at breakfast, to the horror of his host and a circle of aesthetic friends, stood his ground to the last — his physical proportions being his shield and buckler, and his Bible [which he likely shook in the faces of the supporters of female participation in the Convention]. . .his weapon of defence. The movement for woman's suffrage, both in England and America, may be dated from the World's Anti-Slavery Convention. Source: Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joselyn Gage, eds., History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 1 (New York: Fowler and Wells, 1881), 53-54, 61-62. Frederick Douglass Abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass was born into slavery in Talbot County, Maryland. He became one of the most famous intellectuals of his time, advising presidents and lecturing to thousands on a range of causes, including women’s rights and Irish home rule. Among Douglass’ writings are several autobiographies eloquently describing his experiences in slavery and his life after the Civil War. "If there is no struggle there is no progress. . . . Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will."– Frederick Douglass Life in Slavery Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born into slavery in Talbot County, Maryland, around 1818. The exact year and date of Douglass' birth are unknown, though later in life he chose to celebrate it on February 14. Douglass lived with his maternal grandmother, Betty Bailey. At a young age, Douglass was selected in live in the home of the plantation owners, one of whom may have been his father. His mother, an intermittent presence in his life, died when he was around 10. Frederick Douglass was given to Lucretia Auld, the wife of Thomas Auld, following the death of his master. Lucretia sent Frederick to serve her brother-in-law, Hugh Auld, at his Baltimore home. It was at the Auld home that Frederick Douglass first acquired the skills that would vault him to national celebrity. Defying a ban on teaching slaves to read and write, Hugh Auld’s wife Sophia taught Douglass the alphabet when he was around 12. When Hugh Auld forbade his wife’s lessons, Douglass continued to learn from white children and others in the neighborhood. It was through reading that Douglass’ ideological opposition to slavery began to take shape. He read newspapers avidly, and sought out political writing and literature as much as possible. In later years, Douglass credited The Columbian Orator with clarifying and defining his views on human rights. Douglass shared his newfound knowledge with other enslaved people. Hired out to William Freeland, he taught other slaves on the plantation to read the New Testament at a weekly church service. Interest was so great that in any week, more than 40 slaves would attend lessons. Although Freeland did not interfere with the lessons, other local slave owners were less understanding. Armed with clubs and stones, they dispersed the congregation permanently. In 1833, Thomas Auld took Douglass back from his son Hugh following a dispute. Thomas Auld sent Douglass to work for Edward Covey, who had a reputation as a "slave-breaker.” Covey’s constant abuse did nearly break the 16-year-old Douglass psychologically. Eventually, however, Douglass fought back, in a scene rendered powerfully in his first autobiography. After losing a physical confrontation with Douglass, Covey never beat him again. Freedom and Abolitionism Frederick Douglass tried to escape from slavery twice before he succeeded. He was assisted in his final attempt by Anna Murray, a free black woman in Baltimore with whom Douglass had fallen in love. On September 3, 1838, Douglass boarded a train to Havre de Grace, Maryland. At the urging of William Lloyd Garrison, Douglass wrote and published his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, in 1845. The book was a bestseller in the United States and was translated into several European languages. Although the book garnered Douglass many fans, some critics expressed doubt that a former slave with no formal education could have produced such elegant prose. Douglass published three versions of his autobiography during his lifetime, revising and expanding on his work each time. My Bondage and My Freedom appeared in 1855. In 1881, Douglass published Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, which he revised in 1892. Fame had its drawbacks for a runaway slave. Following the publication of his autobiography, Douglass departed for Ireland to evade recapture. Douglass set sail for Liverpool on August 16, 1845, arriving in Ireland as the Irish Potato Famine was beginning. He remained in Ireland and Britain for two years, speaking to large crowds on the evils of slavery. During this time, Douglass’ British supporters gathered funds to purchase his legal freedom. In 1847, Douglass returned to the United States a free man. Upon his return, Douglass produced some abolitionist newspapers: The North Star, Frederick Douglass Weekly, Frederick Douglass' Paper, Douglass' Monthly and New National Era. The motto of The North Star was "Right is of no Sex – Truth is of no Color – God is the Father of us all, and we are all brethren." In addition to abolition, Douglass became an outspoken supporter of women’s rights. In 1848, he was the only African American to attend the first women's rights convention at Seneca Falls, New York. Angelina and Sarah Grimke Angelina and Sarah Grimke were born in the upper-class South, but rejected their lifestyles and began to fight slavery as young women. Sarah Moore Grimke and Angelina Emily Grimké were the only white people of either gender who were born in the upper-class South, but rejected that luxurious lifestyle to fight against slavery. They also were among the very first to see the close connection between abolitionism and women’s rights. Sarah was born on November 26, 1792, and Angelina was born on February 20, 1805. The sisters grew up in a wealthy slave-holding South Carolina family. They had all the privileges of Charleston society – the heart of ante-bellum Dixie -but grew to strongly disapprove of slavery. Their large family so strongly disagreed with them that the Sarah, the older, did not tell anyone when she secretly taught slave children to read, something that violated state law. In 1821, Sarah moved to Philadelphia and became a Quaker, and Angelina followed the same path a few years later, moving to Philadelphia in 1829. Angelina joined the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society and wrote letters to newspapers protesting slavery from a woman’s point of view. This attracted the attention of abolitionists, who enlisted the Grimkes in the cause because they knew the cruelties of slavery firsthand. The sisters were attacked most strongly when they began to make public speeches to audiences consisting of both genders, a practice that was considered shocking. In 1836, after Sarah was reprimanded for speaking at a Quaker meeting about abolition, the sisters moved to New York to work for its Anti-Slavery Society. New York was even less fertile ground for abolitionists than Quaker-based Philadelphia, however, and the sisters continued to be criticized for their “unnatural” behavior in public speaking. They also began to write. Angelina’s Appeal to the Christian Women of the South (1836) was truly a courageous work. She not only discussed how slavery hurt blacks, but also how it damaged white women and the institution of the family. Southern society condoned male sexuality outside of marriage, with the result that “the faces of many black children bore silent testimony to their white fathers.” Postmasters seized and destroyed many of the copies, and hostility towards the Grimke sisters was so great that they never again would be able to visit their South Carolina home. Despite this uproar, they continued. Sarah addressed another audience with Epistle to the Clergymen of the South (1836), and Angelina followed with Appeal to the Women of the Nominally Free States (1837). They toured Massachusetts in the summer of 1837, attracting hundreds of listeners every day; in the town of Lowell, 1,500 people – both men and women – came to hear them speak against slavery. Again, though, many people denounced them for having the audacity to speak to “promiscuous meetings of men and women together.” Clergymen in Massachusetts formally condemned their behavior, pointing out that St. Paul said women should be silent. Undeterred, Angelina Grimke set another precedent in February of 1838, when she became the first woman to speak before a legislative committee; she presented an antislavery petition to Massachusetts lawmakers. In the same year, Sarah published Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Woman (1838). That work predated other feminist theorists by decades. In May of 1838, Angelina married fellow abolitionist Theodore Dwight Weld of Boston, and Sarah moved in with the couple. The next year, Sarah Grimke and Theodore Weld published a remarkable collection of newspaper stories that came directly from Southern papers. American Slavery as It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses (1839) used the actual words of white Southerners in describing escaped slaves, slave auctions, and other incidents that demonstrated how routinely gross inhumanity was accepted as a natural part of the plantation economy. Again, the effect was shocking. Like the Grimkes, Weld was a member of a prominent family, but wealthy conservatives in both the North and South rejected such idealistic rebels, and the three suffered financially in the next decades. Angelina was 33 at marriage, and her health also deteriorated with the birth of three children, Charles Stuart, Theodore, and Sarah. The three farmed and operated schools in the 1840s and 1850s, moving several times within New Jersey and Massachusetts. During this period, the sisters also experimented with the practical pantsuit-style clothing promoted by Amelia Bloomer, but – like other women’s rights leaders – they gave it up when their appearance distracted from their ideas. They finally retired to the Hyde Park section of Boston in 1864. By then, the Civil War was in its last full year, and the sisters’ activism would switch to women’s rights. When the U.S. Constitution was amended to give civil rights to former slaves after the war, the Grimke sisters were among those who tested the gender-neutral language of the Fifteenth Amendment that granted the vote. They attempted to cast ballots in the 1870 election, but male Hyde Park officials rejected them and other women. They also continued their efforts on behalf of racial equality. In 1868, Angelina and Sarah discovered that they had two nephews, Archibald Henry and Francis James, who were the sons of their brother Henry and a slave woman. In accordance with their beliefs, the sisters welcomed the boys into their family. One of them would marry Charlotte Forten, an outstanding Philadelphia black woman, and the sisters’ feminist legacy would continue through Charlotte Forten Grimke. Sarah was nearly 80 when she attempted to vote for the first time, and she died three years later, two days prior to Christmas of 1873. Angelina Grimke Weld suffered a debilitating stroke and died on October 26, 1879. Weld lived on until 1895, but he never was as radical as the women. In the process of fighting against slavery, the Grimké sisters discovered the prejudices that women face, and their cause joined abolitionism and the early women’s rights movement together. They showed more courage than any white person in the South of their times, sacrificing both luxury and their family relationships to work for African-American freedom. A century later, the Grimke story had been largely forgotten: biographical dictionaries, for example, published entries on Weld without mentioning that Sarah Grimke was his co-author. Feminist historian Gerda Lerner revived interest in the sisters’ vital contribution to American history with a 1967 book, and it set the standard for modern women’s history. Charlotte Forten was born on August 17, 1837, in Philadelphia, PA. She kept a diary of her involvement with the abolition movement and became the first African-American hired to teach white students in Salem, MA. In 1862, Forten participated in the Port Royal Experiment, educating ex-slaves on St. Helena Island, South Carolina and recording her experiences in a series of essays. She died in 1914. Educator, writer, and activist. Born on August 17, 1837, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Born into a wealthy and influential African-American family, Charlotte Forten is best known for her personal writings, which offered insights into late 19th century America. Her diaries chronicle the social and political issues of the times—the fight to end slavery, the Civil War, and the state of race relations. Forten had a very comfortable upbringing. Her grandfather, James Forten, helped make his fortune with an invention that assisted sailors with heavy sails. He was an outspoken member of the abolitionist movement and supporter of William Lloyd Garrison's antislavery publication The Liberator. Forten's parents were also active in the movement. Her mother, Mary, helped establish the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, and her father Robert often lectured in support of the abolitionist cause. When Forten was 3 years old, her mother died. An only child, Forten spent much of her early years in solitude, educated by tutors. When she was of school age, her father decided to send her to an integrated school in Salem, Massachusetts, where she lived with the Remond family. While living on the East Coast, Forten began keeping a diary. In it, she wrote about her involvement in the antislavery movement in the Boston area. She deepened her connections to family friends in the movement, such as Garrison and John Greenleaf Whittier, during her time there. After completing her studies, she became a teacher in Salem. She was the first African-American teacher hired to teach white students in the town. Unfortunately, she had to resign after two years because of ill health. Some reports indicate that she may have had tuberculosis. Returning to Philadelphia, she started writing poetry while she tried to regain her health. In 1862, Forten traveled to St. Helena Island, South Carolina, to work as a teacher. There, she participated in what became known as the Port Royal Experiment. During the Civil War, the Union Army took over Port Royal, a Confederate military base in South Carolina. The area was home to thousands of slaves who had been abandoned by their owners. Many of them lived in isolation on the Sea Islands off the coast. The former slaves were largely illiterate, and some did not know English. The Union Army wanted to help these people learn to live independently on local lands. For 18 months, Forten worked with children, adults and soldiers stationed there as part of this program. The only AfricanAmerican teacher to participate in the experiment, Forten's efforts to help the project became a personal mission. Her efforts often reached outside the classroom, and she found herself visiting the homes of the various families in order to instill "self-pride, self-respect, and self-sufficiency," she once wrote. Forten wrote about her experiences in her diary, and a series of her entries were later published in the form of the essay series "Life on the Sea Islands" for the Atlantic Monthly in 1864. Once again, Forten had to abandon her work for health reasons. She began to experience terrible headaches and went home to Philadelphia in 1864. For several years, Forten worked for the Teachers Committee of the New England Freemen's Union Commission. She later returned to teaching, spending time in Charleston, South Carolina, and Washington, D.C. In 1878, Forten married Francis J. Grimke, a Presbyterian minister. He was the nephew of two famous social activists, Sarah and Angelina Grimke. The couple had one child together, a daughter named Theodora Cornelia, who died during her infancy. Throughout the rest of her life, Forten wrote and spoke out on social issues, including women's rights and racial prejudice. She also supported her husband's work at the Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church in Washington, D.C. Forten died on July 23, 1914, in Washington, D.C. Her diaries, which have been published numerous times over the years, have proved to be her most lasting legacy. With her writings, she has provided an eyewitness account of such a pivotal and turbulent time in American history. Forten also offers her readers a glimpse at such famous figures as Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and many other leading activists of her day. Elizabeth Cady Stanton Born on November 12, 1815, in Johnstown, New York, Elizabeth Cady Stanton was an abolitionist and leading figure of the early woman's movement. An eloquent writer, her Declaration of Sentiments was a revolutionary call for women's rights across a variety of spectrums. Stanton was the president of the National Woman Suffrage Association for 20 years and worked closely with Susan B. Anthony. Early Life Women's rights activist, feminist, editor, and writer. Born on November 12, 1815, in Johnstown, New York. The daughter of a lawyer who made no secret of his preference for another son, she early showed her desire to excel in intellectual and other "male" spheres. She graduated from the Emma Willard's Troy Female Seminary in 1832 and then was drawn to the abolitionist, temperance, and women's rights movements through visits to the home of her cousin, the reformer Gerrit Smith. In 1840 Elizabeth Cady Stanton married a reformer Henry Stanton (omitting “obey” from the marriage oath), and they went at once to the World's Anti-Slavery Convention in London, where she joined other women in objecting to their exclusion from the assembly. On returning to the United States, Elizabeth and Henry had seven children while he studied and practiced law, and eventually they settled in Seneca Falls, New York. Women's Rights Movement With Lucretia Mott and several other women, Elizabeth Cady Stanton held the famous Seneca Falls Convention in July 1848. At this meeting, the attendees drew up its “Declaration of Sentiments” and took the lead in proposing that women be granted the right to vote. She continued to write and lecture on women's rights and other reforms of the day. After meeting Susan B Anthony in the early 1850s, she was one of the leaders in promoting women's rights in general (such as divorce) and the right to vote in particular. During the Civil War Elizabeth Cady Stanton concentrated her efforts on abolishing slavery, but afterwards she became even more outspoken in promoting women suffrage. In 1868, she worked with Susan B. Anthony on the Revolution, a militant weekly paper. The two then formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) in 1869. Stanton was the NWSA’s first president - a position she held until 1890. At that time the organization merged with another suffrage group to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Stanton served as the president of the new organization for two years. Later Work As a part of her work on behalf of women’s rights, Elizabeth Cady Stanton often traveled to give lectures and speeches. She called for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution giving women the right to vote. Stanton also worked with Anthony on the first three volumes of the History of Woman Suffrage (1881–6). Matilda Joslyn Gage also worked with the pair on parts of the project. Besides chronicling the history of the suffrage movement, Elizabeth Cady Stanton took on the role religion played in the struggle for equal rights for women. She had long argued that the Bible and organized religion played in denying women their full rights. With her daughter, Harriet Stanton Blatch, she published a critique, The Woman's Bible, which was published in two volumes. The first volume appeared in 1895 and the second in 1898. This brought considerable protest not only from expected religious quarters but from many in the woman suffrage movement. Elizabeth Cady Stanton died on October 26, 1902. More so than many other women in that movement, she was able and willing to speak out on a wide spectrum of issues - from the primacy of legislatures over the courts and constitution, to women's right to ride bicycles - and she deserves to be recognized as one of the more remarkable individuals in American history. Lucretia Coffin Mott (1793-1880) Mott was strongly opposed to slavery and a supporter of William Lloyd Garrison and his American Anti-Slavery Society. She was dedicated to women's rights, publishing her influential Discourse on Woman and founding Swarthmore College. Early Life Women's rights activist, abolitionist and religious reformer Lucretia Mott was born Lucretia Coffin on January 3, 1793, in Nantucket, Massachusetts. A child of Quaker parents, Mott grew up to become a leading social reformer. At the age of 13, she attended a Quaker boarding school in New York State. She stayed on and worked there as a teaching assistant. While at the school, Mott met her future husband James Mott. The couple married in 1811 and lived in Philadelphia. Civil Rights Activist By 1821, Lucretia Mott became a Quaker minister, noted for her speaking abilities. She and her husband went over with the more progressive wing of their faith in 1827. Mott was strongly opposed to slavery, and advocated not buying the products of slave labor, which prompted her husband, always her supporter, to get out of the cotton trade around 1830. In 1833 Mott, along with Mary Ann M’Clintock and nearly 30 other female abolitionists, organized the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. An early supporter of William Lloyd Garrison and his American Anti-Slavery Society, she often found herself threatened with physical violence due to her radical views. Lucretia Mott and her husband attended the famous World's Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1840. It was there that she first met Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who was attending the convention with her husband Henry, a delegate from New York. Mott and Stanton were indignant at the fact that women were excluded from participating in the convention simply because of their gender, and that indignation would result in a discussion about holding a woman’s rights convention. Stanton later recalled this conversation in the History of Woman Suffrage: As Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton wended their way arm in arm down Great Queen Street that night, reviewing the exciting scenes of the day, they agreed to hold a woman’s rights convention on their return to America, as the men to whom they had just listened had manifested their great need of some education on that question. Thus a missionary work for the emancipation of woman…was then and there inaugurated. Eight years later, on July 19 and 20, 1848, Mott, Stanton, Mary Ann M’Clintock, Martha Coffin Wright, and Jane Hunt acted on this idea when they organized the First Woman’s Rights Convention. Throughout her life Mott remained active in both the abolition and women’s rights movements. She continued to speak out against slavery, and in 1866 she became the first president of the American Equal Rights Association, an organization formed to achieve equality for African Americans and women. While remaining within the Hicksite branch of the Society of Friends, in practice and beliefs Mott actually identified increasingly with more liberal and progressive trends in American religious life, even helping to form the Free Religious Association in Boston in 1867. Final Years While keeping up her commitment to women's rights, Mott also maintained the full routine of a mother and housewife, and continued after the Civil War to work for advocating the rights of African Americans. She helped to found Swarthmore College in 1864, continued to attend women's rights conventions, and when the movement split into two factions in 1869, she tried to bring the two together. Mott died on November 11, 1880, in Chelton Hills (now part of Philadelphia), Pennsyvlania. Maria Weston Chapman and the Weston Sisters Maria Weston Chapman (July 25, 1806-July 12, 1885) was described by Lydia Maria Child as "One of the most remarkable women of the age." Chapman and three of her five younger sisters played vital roles in the antislavery movement. Even the smaller Weston girls were pressed into service for the cause that dominated the lives of this family. Chapman, best-known of the group, was a "mainspring" and "lieutenant" of the movement, but her sisters worked closely with her in support of William Lloyd Garrison. They founded an organization, circulated petitions, raised money, wrote and edited numerous publications, and left behind a remarkable correspondence. Maria Weston was the eldest of six daughters and two sons born in Weymouth, Massachusetts, to Warren and Nancy Bates Weston, descendants of the Pilgrims. Maria's birth was followed by those of Caroline in 1808, Anne in 1812, Deborah in 1814, Hervey Eliphaz in 1817, Richard Warren in 1819, Lucia in 1822, and Emma in 1825. The children grew up on the family farm and went to local schools. Joshua Bates, an uncle and prosperous London banker, invited Maria to England to complete her education. Upon her return to Boston in 1828, she became principal of Ebenezer Bailey's Young Ladies' High School. In 1830 she married Henry Grafton Chapman, son of Henry Chapman, a wealthy Boston merchant. The Chapmans were members of Federal Street Church, where William Ellery Channing was minister. Unlike most businessmen and most fellow Unitarians, Maria's father-in-law refused to participate in the lucrative cotton trade and supported Garrison's radical call for immediate abolition of slavery. Maria was the only Weston sister to marry. Caroline and Anne were teachers in Boston. Deborah, though she preferred to stay in Weymouth, taught for a time in New Bedford. All four sisters were drawn into the antislavery movement. They were talented, articulate, witty, energetic, and good-looking, outstanding individually and formidable as a group. In 1834 Maria, Caroline, Anne, Deborah and eight other women formed the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, "believing slavery to be the direct violation of the laws of God, and productive of a vast amount of misery and crime, and convinced that its abolition can only be effected by an acknowledgment of the justice and necessity of immediate emancipation." When the impeccably gowned and coiffed Mrs. Chapman first appeared at anti-slavery meetings, other women workers suspected her of being a spy. It seemed impossible that this socialite could be sympathetic with the slaves. They soon learned that nothing stood in the way of her dedication and organizational ability. She swept all before her, with her sisters behind her in close formation. A famous incident related to the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society was described by Deborah Weston as "the day when 5,000 men mobbed 45 women." In 1835 English abolitionist George Thompson was touring New England, arousing the anger of those whose livelihood depended upon the cotton industry. Thompson was thought to be attending a meeting of BFASS at the Liberator office. An angry mob converged on the building. Despite the uproar, the women calmly began their meeting with scripture reading and prayer. Fearing for the women's safety, the mayor asked them to leave the building. "If this is the last bulwark of freedom," said Maria, "we may as well die here as anywhere." After being escorted to safety through the crowd of hissing men, the women continued their meeting at the Chapman house nearby. A few days after the mob scene, Maria and Deborah were hissed by three men as they stood on the Chapman doorstep. It became impossible for Maria to walk down the street alone without hearing "odious epithets" shouted after her by shop clerks. Years later Maria wrote that "the members of Dr. Channing's congregation were the mob." No doubt the mob included others besides Unitarians, but influential members of Federal Street Church were unsympathetic with the Chapmans and Westons. Channing himself was only moderately supportive of the anti-slavery movement. Though he denied the right of property in slaves and had, Maria wrote, "benevolent intentions," he showed "neither insight, courage, nor firmness." He opposed immediate emancipation and deplored the formation of anti-slavery associations. "Above all," she added, Channing "deprecated the admission of the coloured race to our ranks." Concerning her minister's opposition to associations, Maria simply responded, "You know I never consider Dr. Channing an authority." The sisters regularly attended various Boston churches and exchanged information as to whether the ministers preached against slavery. Here is Deborah on a Sunday in July, 1835: "I was completely exhausted, listening to his [Rev. Mr. Francis Parkman's] villainy. Went in the afternoon to the free church, heard Mr. [Theodore] Parker. He preached very well, speaking extempore." A year later she reported on Maria's success in getting Henry Ware, Jr., guest minister at Federal Street, to announce a forthcoming BFASS meeting. The incident caused "great excitement." "One man said." Deborah wrote, "no one but Mrs. Chapman would have the impudence to do this. Another said, if Mrs. Chapman will insult the congregation, she must expect to be insulted herself." Such comments from fellow church members led to Maria's disaffection with churches in general. She was nevertheless Unitarian, heart and soul, as seems clear from a Sunday morning conversation with her daughter Elizabeth, who was considering Episcopalianism. "A being who was everywhere and knew all our thoughts," Maria maintained, "must be better pleased with us for doing good to others, than going over 'hair splitting' like heathens and Episcopalians." Sewing the hooks and eyes onto Elizabeth's gown she thought "more acceptable as a work of maternal piety to a benevolent and wise being, than if I had passed time at any church in town: more especially as they had all lost sight of what they were formed for." By 1840 Chapmans and Westons had stopped attending Federal Street Church. Maria turned to abolitionist minister Theodore Parker, and her sisters to John Pierpont, who preached anti-slavery at Hollis Street. Maria's spiritual life did not depend upon church attendance. "Eternity and infinity come in like a flood whenever I open the gates," she wrote, "although God and immortality never were much to me." No Unitarian ministers were among the conservative clergymen who published a pastoral letter in 1837 scolding women abolitionists who departed from their traditional "spheres." In response to this letter Maria published a satirical poem, "The Times that Try Men's Souls," attributing authorship to the "The Lords of Creation." "Confusion has seized us, and all things go wrong,/ The women have leaped from 'their spheres,'/ And instead of fixed stars, shoot as comets along,/And are setting the world by the ears!/ . . . So freely they move in their chosen elipse,/ The 'Lords of Creation'/ do fear an eclipse." The pastoral letter increased a developing split between Garrison with his anti-government motto, "no union with slaveholders," and other abolitionists who insisted upon political engagement. A new anti-slavery organization and a new newspaper, the Abolitionist, were established in competition with Garrisonian institutions. Conflict arose in BFASS as well. Some opposed Anne Weston's proposal that the organization continue to subscribe to Garrison's Liberator. An 1840 vote favored the "new organization" members against the Garrisonians, but in compliance with their pastors, the conservative women gradually dispersed. Maria Chapman, her sisters and friends carried on as the only women's group actively supporting Garrison. Their support was vital. Beginning in 1834 and continuing for many years, the Anti-Slavery Fair and the annual publication, Liberty Bell, raised thousands of dollars. Maria and Anne were chief organizers of the fairs, popular Boston social events. Fom 1839-1846 and intermittently thereafter, the Liberty Bell appeared, modelled on the fashionable gift books of the time. As editor, Maria wrote many pieces herself and pressed her sisters into the work as well as soliciting contributions from such notables as Lydia Maria Child, Eliza Cabot Follen, Wendell Phillips, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, and Harriet Martineau. The Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Convention of 1838 was the only occasion on which Maria Weston Chapman spoke in public. She introduced Angelina Grimke over the howling of a mob which later burned to the ground the building where the inter-racial meeting was held. From 1839-1842, Maria edited the Non-Resistant, another Garrison publication. In 1840 she was elected, along with Lydia Maria Child and Lucretia Mott, to the executive committee of the American AntiSlavery Society and was appointed a Massachusetts delegate to the world convention in London, although she did not attend. In 1844 she served as co-editor of the National Anti-Slavery Standard published in New York. She also edited the Liberator in Garrison's absences. Her lively BFASS reports, Right and Wrong in Boston, appeared from 1836-1844 expressing a view of events not always shared by other members. When "an apparently irreconcilable difference of opinion" arose, Maria stated her intention not to suppress her own views. "I shall never submit to any creation of any society that interferes with my righteous freedom." Throughout their public life, the Weston sisters continued their teaching careers, and Maria managed a family and household which became a center of activity in the anti-slavery movement. The Chapmans frequently entertained the abolitionist circle, including "coloured" guests, and housed out-of-town delegates to meetings. Three daughters and a son were born to the Chapmans between 1831 and 1840. The youngest daughter died of tuberculosis, which also afflicted her father. A trip to the West Indies failed to restore his health. He died in 1842. Nothing assuaged Maria's grief but renewed immersion in anti-slavery work. After Henry Chapman's death, Wendell Phillips was guardian of the Chapman children. In 1848 Maria took them out of the emotional and political hotbed of Boston to complete their education in Europe. She planned to continue her antislavery work abroad, and Caroline Weston joined her. They stopped briefly in England to visit Garrison's supporters there. In the fall son Henry was settled at school in Heidelberg and his sisters in Paris, where Maria and Caroline made their home an outpost of the American anti-slavery movement. Despite the turmoil of the revolution overthrowing Louis Napoleon, Maria quickly found sympathizers for her cause and recruited many French contributors to the Liberty Bell. She and Caroline shopped for items to ship to Anne in Boston for the anti-slavery fairs. During visits to England Maria renewed her friendship with British writer Harriet Martineau, whom she had met in Boston in 1835. Struck by Maria's "rare intellectual accomplishment," her courage, beauty, and clear, sparkling voice, Martineau made this American friend editor of her memoirs, published in 1877 as The Autobiography of Harriet Martineau with Memorials by Maria Weston Chapman. By the time Henry had completed his education, his sister Elizabeth had married a French abolitionist, and the other Weston sisters had joined the Paris group. In 1855 Maria returned to Weymouth, where she lived for the rest of her life. She made extended visits to her son in New York City and worked in his brokerage office. Her grandson, John Jay Chapman, long remembered the creative games she invented for her grandchildren. When the Civil War began, her sisters joined her in Weymouth. With emancipation in 1863, Maria agreed with Garrison that it was time to close down the antislavery organizations. She devoted herself to education for the former slaves. Maria Weston Chapman died of heart disease at 78. By 1890 all the sisters were buried in the Weymouth family plot. The Weston Sisters Papers are in the Anti-Slavery Collection at the Boston Public Library. More correspondence of Maria Weston Chapman can be found at the Schlesinger Library at the Radcliffe Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts and the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts. A number of these letters are printed in Clare Taylor, British and American Abolitionists (1974). In addition to the works mentioned in the article, Chapman wrote Ten Years of Experience (1832); a pamphlet, How Can I Help to Abolish Slavery (1855); antislavery stories; and a novel, Pindar, A True Tale (1840). Many of her poems and hymns were published in the Liberator and in Songs of the Free and Hymns of Christian Freedom (1836). Among the biographical treatments of Maria Weston Chapman and her sisters are Clare Taylor, Women of the AntiSlavery Movement: The Weston Sisters (1995) and two articles by Margaret Munsterberg, "The Weston Sisters and the 'Boston Mob,'" The Boston Public Library Quarterly 9 (October 1957) and "The Weston Sisters and 'The Boston Controversy,'" The Boston Public Library Quarterly 10 (January 1958). Short biographical articles on Chapman include David Johnson, "Biographical Sketch of Maria Weston Chapman," in Standing Before Us: Unitarian Universalist Women and Social Reform, 1776-1936, ed. by Dorothy May Emerson (2000); Alma Lutz, "Maria Weston Chapman." in Notable American Women, ed. by Edward T. James et al. (1971); and Gerald Sorin, "Maria Weston Chapman," in American National Biography (1999). See also Debra Gold Hansen, Strained Sisterhood: Gender and Class in the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society (1993) and Phyllis Cole, "Woman Questions: Emerson, Fuller, and New England Reform" presented at the Massachusetts Historical Society conference, "Transient and Permanent: The Transcendentalist Movement and its Contexts," 1997. Article by Joan Goodwin Susan B. Anthony Born in Massachusetts in 1820, Susan B. Anthony was a prominent civil rights leader during the women's suffrage movement of the 1800s. She had become involved in the anti-slavery movement, and it was in doing that work that she encountered gender inequality. With Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Anthony began working to establish women's right to vote. She also created a weekly paper called Revolution, co-founded the National Woman Suffrage Association, and gave many lectures in the United States and in Europe. "Oh, if I could but live another century and see the fruition of all the work for women! There is so much yet to be done." – Susan B. Anthony Early Life Born Susan Brownell Anthony on February 15, 1820, in Adams, Massachusetts, Susan B. Anthony grew up in a Quaker family. She developed a strong moral compass early on, and spent much of her life working on social causes. Anthony was the second oldest of eight children to a local cotton mill owner and his wife. The family moved to Battenville, New York, in 1826. Around this time, Anthony was sent to study at a Quaker school near Philadelphia. After her father's business failed in the late 1830s, Anthony returned home to help her family make ends meet, and found work as a teacher. The Anthonys moved to a farm in the Rochester, New York area, in the mid-1840s. There, they became involved in the fight to end slavery, also known as the abolitionist movement. The Anthonys' farm served as a meeting place for such famed abolitionists as Frederick Douglass. Around this time, Anthony became the head of the girls' department at Canajoharie Academy—a post she held for two years. Leading Activist Leaving the Canajoharie Academy in 1849, Anthony soon devoted more of her time to social issues. In 1851, she attended an anti-slavery conference, where she met Elizabeth Cady Stanton. She was also involved in the temperance movement, aimed at limiting or completely stopping the production and sale of alcohol. She was inspired to fight for women's rights while campaigning against alcohol. Anthony was denied a chance to speak at a temperance convention because she was a woman, and later realized that no one would take women in politics seriously unless they had the right to vote. Anthony and Stanton established the Women's New York State Temperance Society in 1852. Before long, the pair were also fighting for women's rights. They formed the New York State Woman's Rights Committee. Anthony also started up petitions for women to have the right to own property and to vote. She traveled extensively, campaigning on the behalf of women. In 1856, Anthony began working as an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society. She spent years promoting the society's cause up until the Civil War. Women's Right to Vote After the Civil War, Anthony began focus more on women's rights. She helped establish the American Equal Rights Association in 1866 with Stanton, calling for the same rights to be granted to all regardless of race or sex. Anthony and Stanton created and produced The Revolution, a weekly publication that lobbied for women's rights in 1868. The newspaper's motto was "Men their rights, and nothing more; women their rights, and nothing less." In 1869, Anthony and Stanton founded the National Woman Suffrage Association. Anthony was tireless in her efforts, giving speeches around the country to convince others to support a woman's right to vote. She even took matters into her own hands in 1872, when she voted illegally in the presidential election. Anthony was arrested for the crime, and she unsuccessfully fought the charges; she was fined $100, which she never paid. In the early 1880s, Anthony published the first volume of History of Woman Suffrage—a project that she co-edited with Stanton, Ida Husted Harper and Matilda Joslin Gage. Several more volumes would follow. Anthony also helped Harper to record her own story, which resulted in the 1898 work The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony: A Story of the Evolution of the Status of Women. Death and Legacy Even in her later years, Anthony never gave up on her fight for women's suffrage. In 1905, she met with President Theodore Roosevelt in Washington, D.C., to lobby for an amendment to give women the right to vote. Anthony died the following year, on March 13, 1906, at the age of 86, at her home in Rochester, New York. According to her obituary in The New York Times, shortly before her death, Anthony told friend Anna Shaw, "To think I have had more than 60 years of hard struggle for a little liberty, and then to die without it seems so cruel." It wouldn't be until 14 years after Anthony's death—in 1920—that the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, giving all adult women the right to vote, was passed. In recognition of her dedication and hard work, the U.S. Treasury Department put Anthony's portrait on dollar coins in 1979, making her the first woman to be so honored. Sarah McKim Sarah McKim was the wife of James Miller McKim, a prominent abolitionist and Presbyterian minister, who also served as editor for the Pennsylvania Freeman. Sarah was born in Carlisle, PA. Her maiden name was Sarah Allibone Speakman and she married James McKim on October 1, 1840. A brilliant young lawyer, James McKim was frequently called to represent free men and freed men kidnapped across the border into Maryland. He was most famous as the secretary of the Pennsylvania Abolitionist Society and was prominently featured along with William Stills in the renowned illustration of the arrival of Henry ”Box” Brown. Like her husband, Sarah McKim was a strong supporter of the anti-slavery movement and some of her friends and associates included Lucretia Mott, William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglas, Harriet Tubman and Frances Harper. Sarah and her husband became influential supporters of the underground railroad organizations centered in Philadelphia also assisting in the many court cases that emerged after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law. They would make trips to various cities in Pennsylvania from Pittsburg to Philadelphia and Gettysburg to Erie representing the Pennsylvania Abolitionist Society to assist in legal cases and speak on behalf of those who were being persecuted and needed support. Additionally, through her role as an officer in the women’s anti-slavery movement, Sarah met abolitionist Mary Peck Bond with whom she forged a lifetime friendship as her husband did with William Peck. In 1859, with the impending execution of abolitionist John Brown, the McKims lent their support to his wife, Mary Brown and traveled with her to Virginia. Sarah and James prayed and held hands with Mary until the hour of John’s execution had passed. Afterward, the McKims and Frances Harper assisted Mary in claiming her husband's body and escorted her northward, for the funeral service and interment. Sarah also lent her support during the trial of William Stills and 5 Black dock workers, accused of helping in the liberation of Jane Johnson, an enslaved Southern woman who asked for help in obtaining her freedom while passing through Philadelphia with those she served. Jane made an appearance in the courtroom as surprise witness escorted by Sarah McKim and a cadre of female abolitionists such as Lucretia Mott, Sarah Pugh, and Rebecca Plumly. Jane testified that she had not been forcibly abducted by Stills and the other men, but that she had sought freedom out of her own volition. Still and the other 5 men were acquitted. During the Civil War, Sarah McKim’s husband founded the Philadelphia Port Royal Relief Committee to help provide for the liberated freedom seekers of Port Royal. The organization became statewide in 1863 as the Pennsylvania Freedman’s Relief Association. He also became actively involved in the authorizing and the recruiting of African-American units to the Union Army. Two years later, The McKims moved to New York City when James became the first secretary of the new American Freedman’s Union Commission, which operated until 1869. He also helped to found The Nation, a New York newspaper produced to support the interests of the newly freed men and provided Wendell Garrison the position of editor. James and Sarah had two natural children, Charles Follen and Lucy; the couple also adopted James’ niece. Lucy McKim later married Wendell Phillips Garrison, son of William Lloyd Garrison, while the adopted niece became William Garrison’s second wife. Eventually, the McKims relocated to Orange, New Jersey, where James died in 1874. Sarah also stayed in New Jersey until her death in 1891. Sarah Pugh Born: 1800 Birthplace: Virginia Died: 1884 Location of death: Philadelphia, PA Cause of death: unspecified Remains: Buried, Fair Hill Burial Ground, Philadelphia, PA Gender: Female Religion: Quaker , but eventually withdrew from the Orthodox Quakers and never rejoined any religious organization, explaining that she disliked their doctrinal disputes that distracted from enacting beliefs in pursuit of social justice. Race or Ethnicity: White Occupation: Teacher, Activist/organizer/agent of PFASS Nationality: United States High School: Westtown Boarding School, Philadelphia, PA Teacher: Friends School, Philadelphia, PA (1821-1860s) Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society President (1833-1870), Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society Sarah Pugh was a 19th century schoolteacher and abolitionist. She founded her own school and in 1835, she became devoted to the immediate abolition of slavery. She was co-founder and leader of the influential Philadelphia Female AntiSlavery Society, a women's group open to all races. In 1838 the Second Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women met in Philadelphia. Abolitionist Abby Kelley Foster was one of the daring women who spoke to a mixed gender audience. The experience encouraged her to more vocally express her beliefs that women and men should be equal participants in the abolition movement, particularly at conventions like the New England Anti-Slavery Convention. Two years later in 1840, William Lloyd Garrison nominated Kelley to the American Anti-Slavery Society's business committee, despite opposition by some of the male participants. The Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Convention of 1838, which also occurred during the three days the Hall was open, was the only occasion on which Maria Weston Chapman (1806-1885), one of the leading female abolitionists and founder of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, spoke publicly. The meeting hall was torched by an angry pro-slavery mob, and the women escaped the building in pairs -- black women arm-in-arm with white women, which left would-be attackers bewildered long enough for all the women to escape. The next day the convention reconvened in Pugh's schoolhouse where they pledged to expand the relationship between blacks and whites. After the Civil War, Pugh helped establish schools for freed slaves. She also worked for the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association. With Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Pugh attended the World Anti-Slavery Conference in London in 1840 -or more accurately, they crashed the meeting. Female delegates had been officially denied registration, but Pugh had written to protest this and advise the organizers that at least three women would be attending. Later, she served as an agent of the PFASS in Europe, working closely with colleagues there, especially with Richard Webb in Ireland. After the US Civil War she established several schools for freed slaves and their children, and became a prominent suffragette. In her mid-70s she signed the Declaration of Rights for Women in 1876. Her closest friends included Lott and Susan B. Anthony, and she was aunt and inspiration to women's and children's rights activist Florence Kelley. Theodore Dwight Weld (1803-1895) was an American reformer, preacher, and editor. He was one of the most-influential leaders in the early phases of the antislavery movement. Theodore Weld was born in Hampton, Conn., on Nov. 23, 1803, the son of a Congregational minister. Sent to PhillipsAndover to prepare for the ministry, he was forced to leave because of failing eyesight; he tried lecturing and later entered Hamilton College in New York. Here he was especially influenced by evangelist Charles Grandison Finney, who conducted revivalist meetings in the area. Weld toured with Finney's "holy band," leaving for Oneida Institute in 1827 to complete his ministerial studies. Weld soon converted to the antislavery cause. "I am deliberately, earnestly, solemnly, with my whole heart and soul and mind and strength," he wrote in 1830, "for the immediate, universal, and total abolition of slavery." The New York philanthropists Lewis and Arthur Tappan hired Weld as an agent for the Society for the Promotion of Manual Labor to lecture and also to choose a site for a theological seminary for Finney. Weld chose Lane Seminary, and when the Tappans installed the Reverend Lyman Beecher as president, Weld remained as a student. However, Weld and other "Lane rebels" left in 1834 to train agents for the new national American Antislavery Society. Weld himself was a powerful speaker, and his famous agents, the "Seventy," preached abolition across the West. In 1837, his voice failing, Weld went to New York to edit the society's books and pamphlets. His The Bible against Slavery (1837) summarized religious arguments against slavery, while American Slavery as It Is (1839, published anonymously), a compilation of stories and statistics, served as an arsenal for abolitionist speakers and writers. In 1838 Weld married Angelina Grimké, one of two sisters he had helped train as antislavery speakers. By the late 1830s antislavery forces formed a significant bloc in Congress, led by John Quincy Adams. Weld helped to develop the "petition strategy," which forced the slavery issue into open debate. In 1843, feeling that abolition was established as a political issue, he retired to New York in poor health. In 1854, he founded an interracial school in New Jersey. He died Feb. 3, 1895, in Massachusetts. Weld's passion for anonymity and fear of pride tended to obscure his role in the antislavery movement, on which he exerted an enormous influence. He trained more than a hundred agents for the cause, directed its strategy for a decade, and influenced many of its leaders. Columbia Encyclopedia entry: Weld, Theodore Dwight, 1803-95, American abolitionist, b. Hampton, Conn. In 1825 his family moved to upstate New York, and he entered Hamilton College. While in college he became a disciple of the evangelist Charles G. Finney and was influenced by Charles Stuart, a retired British army officer who urged Weld to enlist in the cause of black emancipation. While studying for the ministry at Oneida Institute he traveled about lecturing on the virtues of manual labor, temperance, and moral reform. After 1830 he became one of the leaders of the antislavery movement working with Arthur Tappan and Lewis Tappan, New York philanthropists, James G. Birney, Gamaliel Bailey, Angelina Grimké, and Sarah Grimké. He married Angelina Grimké in 1838. Weld chose Lane Seminary at Cincinnati, Ohio, for the ministerial training of other Finney converts and studied there until the famous antislavery debates he organized (1834) among the students led to his dismissal. Almost the entire student body then requested dismissal, and it was from these theological students that Weld and Henry B. Stanton selected agents for the American Anti-Slavery Society. The "Seventy," as the agents were called, gave character and direction to the antislavery movement and successfully spread the abolitionist gospel throughout the North. From 1836 to 1840, Weld worked at the New York office of the antislavery society, serving as an editor of the society's paper, the Emancipator, and contributing antislavery articles to newspapers and periodicals. He also directed the national campaign for sending antislavery petitions to Congress and assisted John Quincy Adams when Congress tried Adams for reading petitions in violation of the gag rule. While in Washington he advised the Northern antislavery Whigs, many of whom (e.g., Ben Wade, Thaddeus Stevens) were converted to the cause by Weld or one of his agents. After 1844 he retired from public participation in the movement to found a school, Eaglewood, near Raritan, N.J. During the Civil War, at the urging of William Lloyd Garrison, he came out of retirement to speak for the Union cause and campaign for Republican candidates. Most famous of his writings (none was published under his own name) was American Slavery As It Is (1839), on which Harriet Beecher Stowe partly based Uncle Tom's Cabin and which is regarded as second only to that work in its influence on the antislavery movement. Many historians regard Weld as the most important figure in the abolitionist movement, surpassing even Garrison, but his passion for anonymity long made him an unknown figure in American history. Bibliography See Letters of Theodore Dwight Weld, Angelina Grimké Weld and Sarah Grimké 1822-1844, ed. by G. H. Barnes and D. L. Dumond (2 vol., 1934); biography by B. P. Thomas (1950); G. H. Barnes, The Antislavery Impulse, 1830-1844 (1933). William Lloyd Garrison and The Liberator (1805-1879) Every movement needs a voice. For the entire generation of people that grew up in the years that led to the Civil War, William Lloyd Garrison was the voice of Abolitionism. Originally a supporter of colonization, Garrison changed his position and became the leader of the emerging anti-slavery movement. His publication, The Liberator, reached thousands of individuals worldwide. His ceaseless, uncompromising position on the moral outrage that was slavery made him loved and hated by many Americans. Although The Liberator was Garrison's most prominent abolitionist activity, he had been involved in the fight to end slavery for years prior to its publication. In 1831, Garrison published the first edition of The Liberator. His words, "I am in earnest — I will not equivocate — I will not excuse — I will not retreat a single inch — AND I WILL BE HEARD," clarified the position of the New Abolitionists. Garrison was not interested in compromise. He founded the New England Anti-Slavery Society the following year. In 1833, he met with delegates from around the nation to form the American Anti-Slavery Society. Garrison saw his cause as worldwide. With the aid of his supporters, he traveled overseas to garner support from Europeans. He was, indeed, a global crusader. But Garrison needed a lot of help. The Liberator would not have been successful had it not been for the free blacks who subscribed. Approximately seventy-five percent of the readers were free African-Americans. Garrison saw moral persuasion as the only means to end slavery. To him the task was simple: show people how immoral slavery was and they would join in the campaign to end it. He disdained politics, for he saw the political world as an arena of compromise. A group split from Garrison in the 1840s to run candidates for president on the Liberty Party ticket. Garrison was not dismayed. Once in Boston, he was dragged through the streets and nearly killed. A bounty of $4000 was placed on his head. In 1854, he publicly burned a copy of the Constitution because it permitted slavery. He called for the north to secede from the Union to sever the ties with the slaveholding south. William Lloyd Garrison lived long enough to see the Union come apart under the weight of slavery. He survived to see Abraham Lincoln issue the Emancipation Proclamation during the Civil War. Thirty-four years after first publishing The Liberator, Garrison saw the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution go into effect, banning slavery forever. It took a lifetime of work. But in the end, the morality of his position held sway.