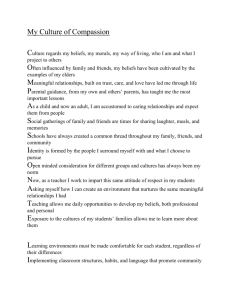

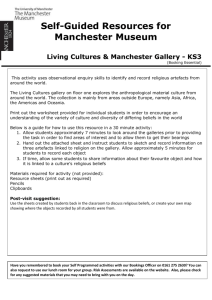

Module: Culture, Beliefs, Values and Ethics

advertisement