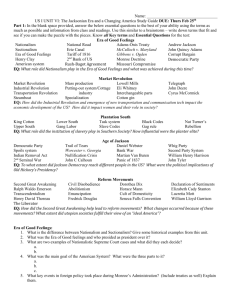

Units VII-VIII Unit VIII The election to the presidency of the frontier

advertisement

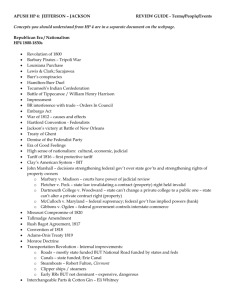

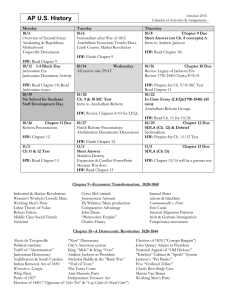

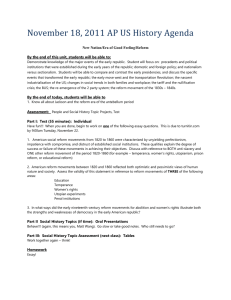

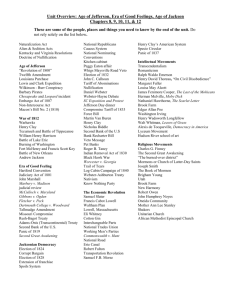

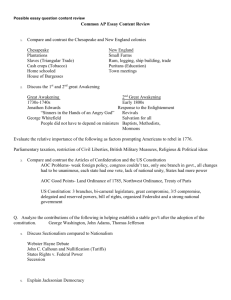

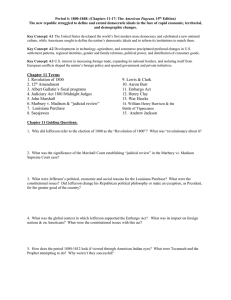

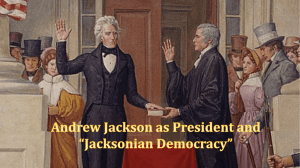

Units VII-VIII Unit VIII The election to the presidency of the frontier aristocrat and common person’s hero, Andrew Jackson, signaled the end of the older elitist political leadership represented by John Quincy Adams. A new spirit of mass democracy and popular involvement swept through American society, bringing new energy, as well as conflict and corruption to public life. Jackson successfully mobilized the techniques of the New Democracy and presidential power to win a series of dramatic political battles against his enemies. But by the late 1830s, his Whig opponents had learned to use the same popular political weapons against the Democrats, signaling the emergence of the second American party system. Amidst the whirl of democratic politics, issues of tariffs, financial instability, Indian policy, and possible expansion in Texas indicated that difficult sectional and economic problems were festering beneath the surface and not being very successfully addressed. Conflict over the tariff of 1828 and 1832 revealed deepening sectional differences. Opponents of the tariff claimed that individual states could nullify federal laws deemed harmful to their interests. Jackson disagreed and threatened to use the military to enforce federal acts and laws. John C. Calhoun, in essence, was making the claim that the US was a confederation of states. Seeing the Bank of the US as a vestige of elite control of the economy, Jackson battled with its president, Nicholas Biddle. Jackson finally defeated the Bank of the US with the Specie Circular. Even though the Supreme Court, in McCulloch v. MD, had ruled the Bank constitutional, Jackson had his way, but it precipitated economic collapse. Unit VII The importance of the West grew in the early nineteenth century. Cheap land attracted immigrants and natives alike, and after some technological innovations, the West became an agricultural giant. The increased output also spurred transportation developments to tie this developing region to the rest of the US. In the era of Jacksonian democracy, the American population grew rapidly and changed in character. More people lived in the raw West and in the expanding cities, and immigrant groups, like the Irish and Germans, added their labor power to America’s economy, sometimes arousing hostility from native-born Americans in the process. Arriving in huge numbers in the antebellum period, these immigrants coalesced into voting blocks, allowing them to play a significant role in the nation’s municipal, state, and federal elections. Concurrently, organizations and political parties, such as the Know-Nothings, formed to fight what they considered a weakening of American culture because of immigration. In the early nineteenth century, the American economy developed the beginnings of industrialization. The greatest advances occurred in transportation, as canals and railroads bound the Union together into a continental economy with strong regional specialization. Industrialization was mainly a northern phenomenon. The southern economy was comparatively stagnant and lacked diversity. Consequently, the two dominant classes, the industrial and merchant capitalist in the North and the planter-slaveholder in the South, wanted political and economic regulations and laws contrary to the other’s needs. For example, northern manufacturers favored a high protective tariff, which was not in the interest of the planterslaveholders. The economic interdependence between the Northeast and the West would play a role in the debate over the expansion of slavery. This relationship grew so strong that the regions would ally against the Confederacy. The spectacular religious revivals of the Second Great Awakening reversed a trend toward secular rationalism in American culture and helped to fuel a spirit of social reform. In the process, religion was increasingly feminized, while women, in turn, took the lead in movements of reform, including those designed to improve their own condition. Historians debate whether the term “Jacksonian democracy” is accurate. Some see Jackson as a representative of the common man at the center of the era’s democratizing spirit. Others see Jackson as indifferent to some reform movements (such as women’s suffrage), opposed to others (abolitionism – he was a slave owner), or unaware of others (possibly urban reform). They hold that grassroots movements of the 1830s, 40s, and 50s were the primary impetus for reform. The attempt to improve Americans’ faith, morals, and character affected nearly all areas of American life and culture, including education, the family, literature, and the arts – culminating in the great crusade against slavery. Some reform movements advocated challenging the social, economic, and ideological status quo. Advocates of women’s rights, for example, challenged the stereotypes that associated women with a “cult of domesticity.” Abolitionists challenged the institution of slavery. For their part, temperance advocates fumed that American civilization and culture were being undermined by “demon rum.” Intellectual and cultural development in America was less prolific than in Europe, but they did earn some international recognition and became more distinctly American, especially after the War of 1812.