Supplemental Materials Overcoming the Educational Disadvantages

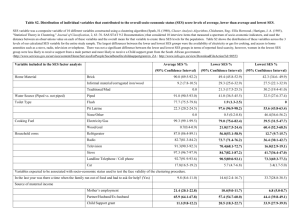

advertisement

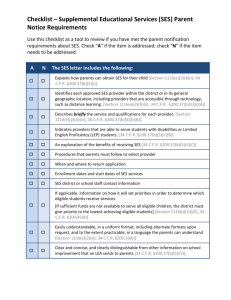

Supplemental Materials Overcoming the Educational Disadvantages of Poor Children: How Much Do Teacher Preparation, Workload, and Expectations Matter by O. Barbarin & N. Aikens, 2015, Orthopsychiatry http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ort0000060 Method The data used in the present study come from the ECLS-K. The ECLS-K study followed a nationally representative sample of American children from kindergarten through eighth grade and provided a comprehensive picture of children’s early school experiences. The total sample consisted of 21,260 children recruited from 1,277 kindergarten classrooms in public, Catholic, and non-Catholic private schools nationwide. Of these children, 16,165 remained in the sample in the spring of the first grade year and were at grade level. The study design involves multistage probability sampling to achieve a nationally representative sample of children eligible to attend kindergarten in the 1998-99 school year. A complete account of the sampling procedures, design and measures used by the ECLS-K can be found in the study manual (U. S. Department of Education, 2002). Study Sample All children attending first grade in the spring first grade frame with a reading assessment score were retained in the analytic sample. This largely excluded language minority children because children unable to demonstrate proficiency in understanding English were not administered the standard reading assessment. In addition, because the hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) software’s listwise deletion of cases with missing data at levels two and three of the hierarchical model, children who were missing data on predictors at these levels were omitted from the sample. Thus, the present analytic sample includes data on 8,118 children, 2,135 classrooms, and 851 schools. When weighted, this represents data on 3,247,698 children. Gender distribution in the analytic sample was close to equal. The ethnic makeup of the sample was 66% White, 13% Black, 15% Latino, and 2% other. About 18% of the children live in household with incomes below the poverty line. Compared to the total sample, the analytic sample is slightly more white and less poor. Measures Assessment of reading skills. Unlike kindergarten programs, which vary in length and curricula, first-grade programs are guided by more explicit and formal standards. This is especially true under the Common Core Standards adopted by many states. As a result, children tend to make much greater reading gains during the first grade year than in kindergarten (Aikens & Barbarin, 2008; McCoach, O’Connell, Reis, & Levitt, 2006). By the end of first grade, most American children display early signs of reading competence. However, there is great disparity across SES groups in the level of competence children attain. Children who fail to read at grade level by the end of first grade often struggle throughout their time in school. Because classroom curricula typically move away from basic reading instruction after first grade (Chall, 1983; Leach, Scarborough, & Rescorla, 2003), reading skills attained by the end of the first grade year are particularly important and predictive of later learning in other subjects. Multiple choice or open-ended formats were used in the ECLS-K to assess basis skills (print familiarity, letter recognition, mastery of beginning and ending sounds, rhyming sounds, word recognition); receptive vocabulary; and comprehension (listening comprehension, words in context). Items for the reading assessment were adopted with permission from published tests including the Peabody Individual Achievement Test-Revised (PIAT-R), Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised (PPVT-R), the Primary Test of Cognitive Skills (PTCS), the Test of Early Reading Ability (TERA-2), and the Woodcock- Johnson Tests of Achievement-Revised (WJ-R). The reading assessment was administered in the spring of the first grade year, using computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) in a classroom or library during school hours. Most assessments were completed in English (97.6%) and took approximately 50 to 70 min per child. Child demographics. Gender was dummy coded (0= Male, 1=Female). Children of all races were included in the current analyses, but three dichotomous dummy variables for Black, Latino, and Asian children were modeled as predictors of reading development. SES was indexed using a combination of parents’ years of education, their occupational prestige (from the 1989 General Social Survey [GSS]), and annual household income. A categorical index was developed to split the continuous SES scores into quintiles, with lower scores indicating lower SES. Teacher questionnaires. Teachers completed questionnaires on classroom instructional practices, student demographics, teaching resources, and their qualifications and expectations of student success. Teaching facilities refers to the availability of a reading area with books, writing center or area, listening center, and computer area in the classroom. Teaching materials refers to teachers’ ratings regarding access and adequacy of trade books, textbooks, workbooks, and basal readers for use in the classroom. The rating scale was as follows: 0 = I never use these at this grade level, 1 = Never adequate, 2 = Often not adequate, 3 = Sometimes not adequate, 4 = Always adequate. Teaching Practice refers to the frequency with which children participated in 11 activities that offered an opportunity to practice reading and writing, e.g. reading aloud or silently, reading texts with controlled vocabulary, hearing stories in which they could see the print, writing in a journal, stories or reports, and using invented spelling (0 = Never, 1 = Once a month or less, 2 = Two or three times a month, 3 = Once or twice a week, 4 = Three or four times a week, 5 = Daily). Teaching load consists of two indicators: the total number of children in the classroom or class size and the number of students in the classroom reading below grade level. Teacher training includes indicators of both pre-service and in-service preparation. This includes the number of reading course taken in college, the highest degree attained, and participation in professional development activities such as conferences, courses, and problem-solving discussions. Teacher experience is captured by two indicators: the total number of years the teacher had been a school teacher and the number of years the teacher had taught first grade. Teacher expectations is an indicator assessing the favorableness of teacher beliefs and expectations about their students’ ability to learn. Teachers rated the extent to which they agreed with the following statement: “Many of the children I teach are not capable of learning the material I am supposed to teach them” They responded using the following scale: 1 = Strongly agree, 2 = Agree, 3 = Neither agree nor disagree, 4 = Disagree, 5 = Strongly disagree. Higher scores reflect more favorable expectations. Overview of Analysis Because the ECLS-K data do not include a simple random sample, analyses took into account the stratification of the survey design and utilized the study’s sampling weights when computing frequency, descriptive information, and tests of statistical significance. AM, a data analysis package designed to analyze complex sample survey data, was utilized for these purposes (American Institutes of Research, http://am.air.org/default.asp). For the present analyses, cross-sectional child sample weights from the ECLS-K first grade data file were used. Probability weights were adjusted for differential probability of selection and non-response, and the clustering weights were used to estimate accurate standard errors. Effect sizes were calculated using t-statistics and associated degrees of freedom, with .10 representing a small effect, .30 a medium effect, and .50 a large effect (Cohen, 1992). Because the present study focused on the effects of school variables on children’s reading outcomes, we used HLM to account for the nesting of children within classroom and classrooms within schools. Accordingly, the model has a three-level nested structure: the individual child level, the classroom level, and the school level. Children’s reading scores, gender, race, and family SES were included at level one, and classroom and teacher resources were included at the second level. School-wide resources and characteristics were included in the third level. This report deals only with the first two levels: child and teacher. In all models, data were weighted at the child level in an effort to account for nonresponse and unequal probabilities of selection. The HLM 6.02 software (Raudenbush, Bryk, & Congdon, 2005) was used to fit the multilevel model. The full maximum likelihood default was used for the estimation of all models. Results The School Environments of Children With Low SES Regression analyses were estimated with the continuous measure of SES serving as the independent variable and demographic, classroom, and teacher characteristics serving as dependent variables. A similar model with children’s spring-first grade reading scores serving as the dependent variable was also estimated. These models indicated that children with low SES had significantly lower reading scores at the end of first grade than their peers, T(324) = 25.75, es = .82, p<.001. They also were significantly more likely to share classrooms with larger proportions of minority students, T(324) = -11.72, es = .55, p<.001 and poor students T(324) = 12.93, es = .58, p<.001. The magnitude of all of these differences ranged from medium to large. Table 1 presents descriptive data on classroom indicators broken down by the five SES levels. Classroom indicators included teaching resources (facilities and materials), teaching practice, and teaching load (class size and below grade level readers). There were no significant SES differences in teaching facilities, materials, practices, or class size. The classrooms of children with low SES had significantly fewer children who were reading at or above grade level, T(324) = -12.18, es = .56, p<.001. However, they tended to be in classrooms with a smaller number of students, T(324) = 3.39, es = .19, p<.001. Table 2 presents descriptive data on teacher characteristics, i.e. training (reading courses, degree, professional development), years of experience (total and in first grade), and expectations of students broken down by SES levels. Children’s teachers did not differ in their number of reading instruction courses or number of professional development activities in which they were involved. Compared to all other SES levels, children in the lowest SES group were taught by less trained and experienced teachers who held less favorable beliefs about their students’ ability to learn. Specifically, teachers of children in the lowest SES group tended to have fewer years of experience teaching first grade, T(324) = 2.60, es = .14, p<.01, fewer years of experience teaching overall, T(324) = 2.78, es = .15, p<.01, and less education, T(324) = 2.77, es = .15, p<.01. Teachers of children with low SES were more likely to have low expectations of students’ ability, T(324) = 5.92, es = .31, p<.001. Among these effect sizes, only the magnitude of the effect of SES on peers reading below grade level and teacher expectations was medium or high; all other effects were small. Relation of SES to Teacher and Classroom Characteristics These results present the conditional model estimating the relationship between family SES and reading achievement and conditional models of within-classroom and within-school effects on reading achievement. The latter analyses show the effects of classroom-level and school-level characteristics on the average reading achievement scores in each classroom and school, respectively. By estimating the interactions of such characteristics with family SES, these final models also provide estimates of the effects of the contextual variables (i.e., peers, teachers, resources, facilities) on the slopes for the relationship between family economic background and reading scores. This permits us to make inferences about the extent to which classroom and teacher factors have the same relation to reading outcomes for poor children as they do for economically advantages children. Family SES was initially included as a level 1 predictor of reading achievement. The regression intercept was allowed to vary randomly across classrooms. With the addition of socioeconomic status in the model, the variance estimate for level 1 was reduced by 5%, suggesting that family socioeconomic status explained only a small portion of the class-to-class variability in mean reading achievement. Prior to adding additional predictors to the model, the magnitude of the relationship between family SES and reading performance was assessed across classrooms. Results from the estimated model, suggested that the magnitude of the relationship did indeed vary across classrooms (??? = 3011.09, p=.000), but not across schools (??? = 581.27, p >.500). As a result, SES was used as a random effect at level 2 for all further models. Relation of teacher and classroom characteristics to reading. Child SES and all classroom and school variables were grand mean centered at 0 in all models to improve interpretation (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002; Singer & Willet, 2003). This approach treats scores at level 1 as the child’s score minus the grand mean, and scores at level 2 as the classroom score minus the grand mean. All variables that were dummy coded already had a valuable meaning for 0 and did not require centering. For estimation purposes, random effects for the classroom, teacher, and school predictors were not added to any of the models. All models converged successfully. HLM coefficients are provided in Tables 3 and 4. Teacher characteristics. Teacher characteristics were added as level 2 predictors of reading achievement. Teacher influences included training (reading courses, highest degree and professional development), experience (total years teaching and years teaching first grade), and expectations. Along with SES, child race, gender, and age in months were also included in level 1 as controls. Higher reading scores were associated with teachers having more experience teaching first grade (T=2.63, es = .06, p=.009) and more favorable expectations for students’ learning (T=4.42, es = .10, p=.000). The magnitude of the effect sizes, however, suggest that the effects for all significant teacher variables were small. Cross-level interactions of family SES and teacher characteristics were also estimated. No significant interactions emerged, suggesting that the relationship between family SES and reading scores was not moderated by the estimated teacher characteristics. Classroom characteristics. In conjunction with teacher characteristics, classroom predictors were added to the model next. Classroom effects included teaching facilities, materials, practice, and load (class size and the number of children reading below grade). Along with SES, the proportion of minority children, child race, gender, and age in months were also included in level 1 as controls. Higher reading scores were associated with more varied teaching practice (T=2.58, es = .06, p=.035); access to teaching materials (T = 2.10, es = .05, p = .035); lower teaching load, i.e. larger class size (T = 2.25, es = .05, p = .025); and fewer classmates reading below grade (T=-8.90, es = .19, p=.000). The magnitude of all effects for variables in the model was small. Interactions of SES and classroom characteristics on reading. Cross-level interactions of family SES and classroom characteristics were also estimated. The interaction for class size was significant, suggesting that the relationship between SES and reading scores was moderated by this classroom characteristic. To probe this effect, the variable for class size was dummy coded to represent classrooms with class sizes one standard deviation below the mean versus those with sizes more than one standard deviation above the mean (Aiken & West, 1991). Results from the model of smaller than average classes indicated that the intercept and slope of the regression line between family SES and reading achievement was 56.09 and 6.91. The intercept and slope of the regression lines for larger than average classes was 55.32 and 6.56. Hence, it appeared that smaller than average classrooms had slightly higher reading scores, and the magnitude of the relationship between family SES and reading scores was steepest within these classrooms. Figure 1 presents a line graph of these results and suggests that low-SES children have lower reading scores when they are in larger than average classrooms than low SES peers in smaller than average classrooms. Class size did not differentiate the reading scores of high-SES children. Table S1 Descriptive Statistics for Classroom and Teacher Characteristics Disaggregated by SES Levels Variables Population % Minority Children in Classroom a 1 (n=556,83 4) 2 (n=627,90 9) 3 (n=674,002) 4 (n=682,55 3) 5 (n=706,39 9) Less Than 10% 18% 29% 36% 39% 45% Between 10 and 25% 10% 15% 16% 23% 25% Between 25 and 50% 15% 20% 20% 18% 18% 50% and Higher 57% 36% 38% 21% 12% Teaching Facilities 3.3 (0.8) 3.4 (0.8) 3.4 (0.8) 3.4 (0.8) 3.4 (0.8) Teaching Materials (std) 11.9 (3.3) 12.0 (3.2) 12.0 (3.2) 12.1 (3.2) 11.9 (3.5) Teaching Practice (std) 53.8 (6.5) 54.1(6.2) 54.0 (6.3) 54.0 (6.1) 54.0 (6.0) Class Size (std) a 19.9 (3.9) 20.3 (3.6) 20.7 (3.7) 20.9 (4.1) 21.1 (4.0) Children Reading Below Grade (std) a 5.7 (3.8) 5.0 (3.5) 4.5 (3.1) 4.0 (2.6) 3.6 (2.4) 48.7 54.3 (12.3) 56.5 (12.0) Child Reading Score (std) a 58.7 (11.8) 63.0 (11.5) (12.0) Note. a p<.001, b p<.01, c p<.05 Number of classrooms = 2,135, schools = 851. Table S2 Teacher Characteristics by SES Quintiles Variables Population Reading Instruction Courses Taken (std) Has Advanced Degree Professional Development Activities (std) 1 (n=556,83 4) 3.5 (2.0) 2 (n=627,90 9) 3.7 (1.9) 3 (n=674,00 2) 3.7 (1.9) 4 (n=682,55 3) 3.7 (1.9) 34% 37% 34% 37% 4.5 (1.7) 4.4 (1.9) 4.5 (1.9) 4.4 (1.9) 5 (n=70 9 3.8 ( 42 4.4 ( Teaching Experience- Total (std) b 12.4 (9.7) 14.2 (10.2) 14.1 (9.8) 14.0 (10.0) 14.7 ( Teaching Experience- First Grade (std) b 7.3 (7.2) 8.4 (8.0) 8.8 (7.9) 8.8 (8.1) 8.8 ( 13% 12% 10% 7% Low Teacher Expectations a Note. Number of classrooms = 2,135, schools = 851. a p<.001, b p<.01, c p<.05. Table S3 HLM Coefficients from the Within-Classroom Model of First Grade Reading Scores Independent Variables Teacher Model Classroom Model Intercept 56. 45 (0.82) a 58.64 (1.60) a Level 1 Variance Component 46.58 44.93 % Variance Explained 9.95 13.13 Child SES 4.92 (0.29) a 4.53 (0.30) a Female 2.41 (0.30) a 2.33 (0.29) a Black -3.04 (0.65) a -2.44 (0.67) a Latino -1.40 (0.62) c -0.84 (0.63) Asian 1.34 (0.83) 1.83 (0.86) c Age 0.10 (0.03) b 0.08 (0.03) c Child Variables Teacher Variables 6% Reading Instruction Courses -0.12 (0.13) -0.15 (0.12) Highest Degree Earned 0.03 (0.26) 0.06 (0.25) Professional Development -0.20 (0.12) -0.27 (0.12) c Teaching Experience- Total -0.04 (0.04) -0.03 (0.04) Teaching Experience- First- 0.11 (0.04) b 0.05 (0.04) -1.14 (0.26) a -0.33 (0.25) Minority Children in Class -- -0.57 (0.20) b Teaching Materials -- 0.15 (0.07) c Teaching Facilities -- -0.10 (0.31) Teaching Practice -- 0.10 (0.04) b Class Size -- 0.16 (0.07) c Children Reading Below Grade -- -0.66 (0.07) c grade Teacher Expectations Classroom Variables Note: Numbers in parentheses are standard errors. Observations are weighted at the child level. a p<.001, b p<.01, c p<.05. Table S4 HLM Coefficients from the Within-Classroom Model of SES by Predictor Interactions on First Grade Reading Scores Independent Variables Teacher Model Classroom Model Intercept 56.41 (0.81) a 58.96 (1.59) a Level 1 Variance Component 46.59 44.19 % Variance Explained 9.92 14.56 Child SES 4.12 (0.94) a 5.55 (1.62) a Female 2.42 (0.30) a 2.33 (0.29) a Black -3.04 (0.65) a -2.45 (0.67) a Latino -1.41 (0.62) c -0.77 (0.63) Asian 1.35 (0.84) 1.81 (0.85) c Age 0.09 (0.04) c 0.08 (0.03) c Reading Instruction Courses 0.01 (0.14) -- Highest Degree Earned 0.45 (0.29) -- Professional Development 0.23 (0.15) -- Total Teaching Experience 0.02 (0.04) -- First-grade Teaching Experience -0.03 (0.04) -- Teacher Expectations 0.30 (0.26) -- Minority Children in Class -- 0.33 (0.19) Teaching Facilities -- 0.06 (0.34) Teaching Materials -- -0.08 (0.08) Teaching Practice -- 0.05 (0.04) Child Variables Teacher Variables X SES Classroom Variables X SES Class Size -- -0.16 (0.08) c Children Reading Below Grade -- -0.03 (0.09) Note: Numbers in parentheses are standard errors. Observations are weighted at the child level. a p<.001, b p<.01, c p<.05.