Chapter 11 … Capital Budgeting and Investment Analysis Chapter

Chapter 11 … Capital Budgeting and Investment Analysis

Chapter Outline

I. Capital Budgeting -- fundamental goal of capital is to earn a satisfactory rate of return. Such decisions require careful analysis, and are the most difficult and risky decisions that managers make because of need to make predictions of events that will occur well into the future. It is also risky because outcome is uncertain, large amounts of money are involved, long-term commitment is required, and decision may be difficult or impossible to reverse.

Several techniques are used to make capital budgeting decisions.

A. Methods Not Using Time Value of Money -- Investments are expected to produce cash inflows and cash outflows; net cash flow equals cash inflows minus cash outflows.

Simple analysis methods do not consider the time value of money.

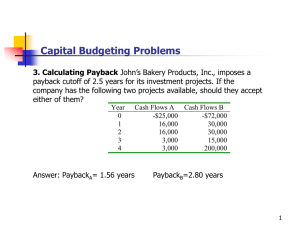

1. Payback Period -- the time period expected to recover the initial investment amount.

That is, the time it will take the investment to generate enough net cash flow to return

(or pay back) the cash initially invested to buy it. Managers prefer investments with shorter payback period. Shorter payback period reduces risk of unprofitable investment over the long run. Company’s risk due to potentially inaccurate long-term predictions of future cash flows is reduced. a. Computing Payback period with Even Cash Flows.

i. When annual cash flows are even in amount, payback

period equals cost of investment divided by annual net

cash flow.

ii. Even cash flows are cash flows that are the same each

and every year; uneven cash flows are cash flows that

are not all equal in amount.

iii. The amount of net cash flow from an asset is computed

by subtracting expected cash outflows from expected

cash inflows.

iv. Cash flows exclude all noncash revenues and expenses.

Depreciation is a noncash item. b. Computing Payback Period with Uneven Cash Flows -- When annual cash flows are unequal, payback period is computed using the cumulative total of net cash flows (starting with the negative cash flow resulting from the initial investment); when cumulative net cash flow changes from positive to negative, the investment is fully recovered. ( Cumulative refers to the a ddition of each period’s net cash flows).

c. Using the Payback Period -- should not be only consideration in evaluating investments; two factors are ignored. i. Differences in the timing of net cash flows within the payback period are not reflected. Investments that provide cash more quickly are more desirable. ii. All cash flows after the point where its costs are fully recovered are ignored.

2. Accounting Rate of Return (or return on average investment)

a. Compute by dividing after-tax net income from project by average amount invested in project. b. Accrual basis after-tax net income is used. c. Average investment must be computed. i. If net cash flows are received evenly, then average investment for any one year is computed as average of beginning and ending book values. ii. Average investment (or average book value for asset’s entire life) is then computed by taking the average of the individual yearly averages. iii. When using straight-line depreciation, average book value equals sum of beginning and ending book values divided by two. iv. If investment has salvage value, the average investment is computed as sum of beginning book value and salvage value divided by two. d. Risk of an investment should be considered. i. Investment ’s return is satisfactory or unsatisfactory only when related to returns from other investments with similar lives and risk. ii. Capital investment with least risk, shortest payback period, and highest return for the longest time is often identified as best; analysis can be challenging because different investments often yield different rankings depending on measure used. e. Accounting rate of return method is readily computed, often used in evaluating investment opportunities, yet usefulness is often limited. i. Amount invested is based on book values for future periods. ii.

If asset’s yearly net incomes vary, average annual net incomes must be used; method fails to distinguish between two investments with same average annual net income when one investment yields higher amounts in early years and the other in later years.

B. Methods Using Time Value of Money

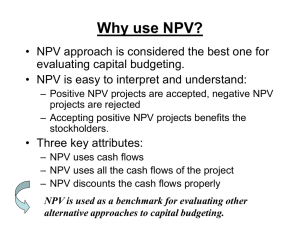

Net present value and internal rate of return methods consider time value of money. Surveys show internal rate of return (IRR) is most popular method, followed by payback period and net present value (NPV). Few companies use accounting rate of return (ARR).

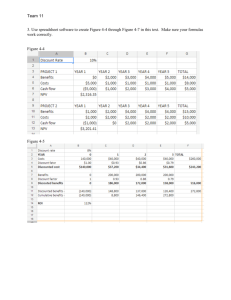

A. Net Present Value (see Appendix B near end of textbook)

To compute NPV, discount the future net cash flows from the investment at the required rate of return, and then subtract the initial amount invested. a. Each annual net cash flow is multiplied by the related present value of 1 factor or

discount factor. (Obtain from Table B.1 in Appendix B.) i. Discount factors assume that net cash flows are received at the end of each year. ii. Rate of return required by the company and number of years until cash flow is

received are used to determine discount factors. b. Initial amount invested includes all costs incurred to get asset in proper location and

ready to use. c. Net Present Value Decision Rule - Sum of present values of annual net cash flows

should be compared to initial amount invested.

If sum of present values of annual net cash flows equals or exceeds initial investment

(that is, if the net present value of all cash flows is positive), then asset is expected to recover its cost and provide a return at least as high as that required; project is accepted.

If net present value is negative, project is rejected.

NPV analysis can be used when comparing several investment opportunities; if investment opportunities have same cost and same risk, the one with highest positive net present value is preferred. d. Simplifying Computations - when annual net cash flows are equal in amount, NPV

calculation can be simplified.

Individual annual present value of 1 factors can be summed, and total multiplied by annual net cash flow to get total present value of net cash flows. e. Uneven Cash Flows - NPV analysis can also be applied when net cash flows are unequal. (Use procedures and decision-rules above.) f. Salvage Value and Accelerated Depreciation - if salvage value is expected at end of useful life, treat as an additional net cash flow re ceived at end of final year of asset’s life.

Accelerated depreciation methods do not change basics of NPV analysis, but can

change results; using accelerated depreciation for tax reporting affects net present value of asset’s cash flows.

Accelerated depreciation produces larger depreciation deductions in early years of asset’s life and smaller ones in later years; large net cash inflows are produced in early years and smaller ones in later years.

Early cash flows are more valuable than later ones; as such, being able to use accelerated depreciation for tax reporting makes investment more desirable. g. Use of Net Present Value – when deciding whether to proceed with a capital

investment project, we approve if NPV is positive but reject if it is negative.

NPV is of limited value for comparison purposes if initial investment differs substantially across projects.

When considering several projects of similar investment amounts and risk levels, we can compare the different NPV’s and rank them on the basis of their NPV’s.

When the projects being compared have different risks, the NPVs of individual projects should be computed using different discount rates; the greater the risk, the higher the discount rate.

B. Internal Rate of Return (IRR) a. IRR is a rate used to evaluate acceptability of an investment; it equals the rate that

yields a NPV of zero for an investment. b. If the total present value of a project’s net cash flows is computed using the IRR as

the discount rate, it will equal the initial investment. c. Computation involves a two-step process:

i. Step One – compute the present value factor for the investment project. Present

value factor = amount invested / net cash flows. ii. Step Two – identify the discount rate (IRR) yielding the present value factor.

Search Table B.3 for a present value factor equal to the present value factor

identified in step one. iii. When cash flows are equal, the present value factor equals the amount invested

divided by the net cash flows. iv. An annuity table (see Appendix B) can be used to determine the discount rate that

relates to this present value factor given the life of the project. v. If the present value factor in the table does not exactly equal the one computed,

the procedure set forth in Exhibit 24..9 can be used to estimate the IRR. d. Uneven Cash Flows - when cash flows are unequal, trial and error must be used;

select any reasonable discount rate and compute the NPV. i. If amount is positive, recompute NPV using higher discount rate; if amount is

negative, recompute NPV using lower discount rate. ii. Continue steps until two consecutive computations result in NPVs that have

different signs (positive and negative); IRR lies between these two discount rates;

value can be estimated. iii. Spreadsheet software can also compute the IRR. e. Use of Internal Rate of Return - compare IRR with a predetermined hurdle rate

which is a minimum acceptable rate of return; if IRR exceeds hurdle rate, accept \

project. i. Choice of hurdle rate is subjective. ii. If project financed from borrowed funds, hurdle rate should exceed interest rate

paid on borrowed funds; return on investment must cover interest and provide

additional profit to reward company for risk. iii. If project is internally financed, hurdle rate is often based on actual returns from

comparable projects. iv. If evaluating multiple projects, rank by extent to which IRR exceeds hurdle rate.

IRR is not subject to limitations of NPV when comparing projects with different

amounts invested; IRR is expressed as percent rather than an absolute dollar

value using NPV.

3. Comparison of Capital Budgeting Methods (see Exhibit 24.10) a. Payback period and accounting rate of return do not consider time value of money;

NPV and IRR do. b. Payback period method is simple; sometimes used when there is a limited amount of

cash to invest and a number of projects to choose from. c. Accounting rate of return is a percent computed using accrual income instead of

cash flows, and is an average rate for the entire investment period; annual returns

are not reflected. d. NPV: i. Considers all estimated cash flows of project; can be applied to equal and

unequal cash flows. ii. Can reflect changes in level of risk over life of project. iii. Difficult to use in comparisons of projects of unequal sizes. e. IRR: i. Considers all estimated cash flows of project. ii. Readily computed when cash flows are equal, but requires trial and error

estimation when cash flows are unequal. iii. Readily used to compare projects with different investment amounts. iv. Does not reflect changes in risk over life of project.

II. Decision Analysis

Break-Even Time

a variation on the payback period method.

A. Start by restating future cash flows in terms of their present values; must discount the

cash flows.

B. Then compute the payback period using the present values of future cash flows.

C. Break-even time (BET) is useful measure; managers know when to expect cash flows to

yield net positive returns.

D. If BET is less that estimated life of investment, positive net present value can be

expected from investment.

E. To compare and rank alternative investment projects, choose the project with the lowest

break-even time.