GregBarton-HFF-IslamIndon-17Oct12

Islam, secularism and liberal democracy in Indonesia

Greg Barton, Monash University

Herb Feith Research Professor for the study of Indonesia

Herb Feith Foundation Seminar Series

Monash Caulfield, 16 October 2012

Are pluralism and tolerance under threat in Indonesia?

Will bullying and violence in the name of

God go unchecked?

What does Bhinneka Tunggal Ika mean today?

May 1998 and democratic transition

Democratic transition

Political legitimacy

Clear support of public

Challenge of credibility

A premature transition to democracy?

Middle class and therefore civil society too small?

Islam – is the world’s largest Muslim nation ready for democracy?

What sort of democracy wiill emerge?

Unexpected success

Awkward transition

New Order and ABRI misread?

Unlikely leaders, unconventional leadership – Habibie and

Wahid

Islam’s ‘dark matter’ – unrecognised civil society

Sources of Legitimacy

• Nationalism

• Democracy

• Islam

– Parties, politicians, policies and the question of legitimacy

>

What has legitimacy?

>

For whom does it have legitimacy?

>

How Islamic is Islamic enough?

Institutional legitimacy deficit

• Whilst the initial phase of Indonesia ’ s democratic transition has now been successfully completed, and the current government enjoys high levels of legitimacy, institutional reform has only just begun

• Indonesia ’ s most important institutions continue to suffer from a serious lack of legitimacy

• This is revealed in a number of social surveys

• In 2007 Pusat Pengkajian Islam dan Masyarakat

(PPIM) at the State Islamic University (UIN) in

Jakarta published three survey reports

3rd 2007 PPIM survey -

Islam and nationalism

• In 2007 PPIM published a social survey with the title

“ Islam and Nationalism: Findings of a National Survey ” .

• Respondents in this survey indicated low levels of trust in political parties and public institutions, especially in the field of law, but relatively high levels of trust in religious leaders.

• Nevertheless the results of this survey also speak of

Indonesia ’ s significant success in building a national identity that transcends ethnicity and regionalism.

Lack of confidence in state institutions

• 8% had confidence in political parties

• 11% trusted the legislature (DPR)

• 16% trusted the police

• 22% trusted both the president and the army as institutions

• 41% had confidence in religious leaders.

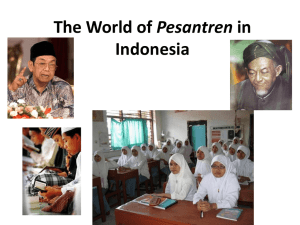

2007 PPIM survey -

Pesantren/madrasah, Islamic schools

• This survey, entitled “ Assessment of Social and Political

Attitudes in Indonesian Schools: Madrasah and

Pesantren Directors and Students ” , focussed on interviewing twelve teachers (ulama: kyai, and ustaz) and senior students from sixty-four pesantren/madrasah and sixteen Islamic schools across eight provinces, giving a total of 960 respondents.

• Considerable care was taken to choose a representative sample of NU and Muhammadiyah institutions together with independent pesantren and urban Islamic schools from among Indonesia ’ s 20,000 pesantren and numerous

madrasah and Islamic schools .

Lack of confidence in state institutions

• It would appear that one reason why shariah law and Islamist politics have such strong support in Indonesia today is that there exists very little confidence in public institutions.

• Less than one in five respondents believed that “ the police perform their law enforcement task well ” (17.5%)

• 19% believe that nation ’ s courts perform their task “ to achieve justice in legal decisions ”

• 22% have confidence in the performance of the House of

Representatives (DPR).

• 49% have confidence in the president ’ s performance of his duties

• 82% believe that “ religious leaders, precisely the ulama, will not mislead them ” .

Support for democracy

• It is interesting that whilst PPIM surveys since 2001 show evidence of increasing support for Islamism they also reveal steadily increasing support for democracy.

Indeed in this 2007 survey high levels of support for

Islamism are accompanied by high levels of support for democracy.

• 86% of respondents agreeing that “ democracy is the best system of governance for Indonesia ” .

• 83% agreed with the statement that “ democracy creates social order within society ” .

Islamic democracy – democratic Islam?

• Radical Islamism represents the most substantial critique of the legitimacy of liberal democracy in

Indonesia

– How much support is there for radical Islamism?

• The world ’ s largest Muslim nation has transitioned to democracy but what does Islam have to do with this?

– Has this occurred because of, or despite, Islam?

– The civil sphere is the place to look for an answer

• What has been the contribution of Islam to civil society in Indonesia?

– This needs to be viewed broadly and over the longer run, as well as in the reform movement of the past two decades

The ‘Arab Spring’: transition in the heart of the Muslim world

Five Implications from the ‘Arab Spring’

• 1. Religion remains important

• 2. Social, economic, political, cultural and demographic drivers are paramount

• 3. Democracy is just beginning

• 4. Secular, liberal democracy needs to be negotiated and developed in the context of local cultural and religious factors

• 5. Religious and social harmony will face variegated and unpredictable challenges

1. Religion remains important

• Religion is generally not the driver for protest

• But it informs values, aspirations and expectations

• And manifests in the market-place of ideas that accompanies democracy

• Religion has played an important historical role in dissent and social services

• Hence, the Muslim Brotherhood is key

2. Social, drivers are paramount

• Social

• Economic

• Political

• Cultural

• Demographic

3. Democracy is just beginning

• The modern nation state is a very recent development

– Most members of the UN were born in the

20 th C

• Democracy is even more recent

• In the MENA nations democracy is arriving for the first time

– it was deferred by Cold War imperatives

4. Secular, liberal democracy needs to be negotiated and developed

• There exists wide-spread desire for democracy

• But it needs to be developed in the context of local cultural and religious factors

• Secularity and the appropriate limits of religion remains a work in progress even in the west

• Secular liberal democracy does not mean the absence of religion in the public square

5. Religious and social harmony will face challenges

• These challenges will be variegated and unpredictable

• Religious sentiments will be manipulated for cheap politics

• Religious leaders and communities must be part of the solution

– But they need wisdom and courage

• More than ever, they will need to work together

Islam must have it's place

• In the ME engaging with culture, tradition and belief requires engaging with Islam

• Democracy requires allowing Islam a place in public discourse, political discourse, social movements and public life in general

• But what should that place be?

• The relationship between religion and the state needs to be mediated through the civil sphere without coercion on any side, independent from the state

• Secular liberal democracy is the only truly popular option but it must find indigenous form and expression

• Religious social movements can play a vital and constructive role

Islam and Modernity

• Can Islam and Islamic social movements be truly modern?

• Binder says yes, but is not sure how.

• Huntington says no, and finds support in radical

Islamist essentialism.

• “ "The underlying problem for the West is not Islamic fundamentalism. It is Islam, a different civilization whose people are convinced of the superiority of their culture and are obsessed with the inferiority of their power." (Huntington, 1996:217-8)

Multiple Narratives

• Traditionalist Muslims

• Modernist Muslims

• ‘ Secular ’ , non-observant cosmopolitans

• Progressive/liberal Muslims

• Moderate Islamists

• Radical Islamists

• Jihadists

Indonesia’s democratic transition

Democratic transition

Political legitimacy

Clear support of public

Challenge of credibility

A premature transition to democracy?

Middle class and therefore civil society too small?

Islam – is the world’s largest Muslim nation ready for democracy?

What sort of democracy wiill emerge?

Unexpected success

Awkward transition

New Order and ABRI misread?

Unlikely leaders, unconventional leadership – Habibie and

Wahid

Islam’s ‘dark matter’ – unrecognised civil society

Joining the BRICs

• Indonesia is now increasingly recognized as a key nation in the emerging second tier of rapidly developing large nations

• joining the likes of Turkey and Mexico

• in the wake of the original BRIC group (Brazil,

Russia, India, and China) of first tier emerging nations.

A present reality

• This is a present reality not merely a long-term projection.

• Over the next eight years Indonesia is on track to overtake Spain, Canada and Italy to become the world's 11th largest economy in 2020

– just behind South Korea

– Indonesia is currently ranked 15th.

2010 v 2020

Brookings – June 2011

World Economic Expansion

Asia’s rising middle class

McKinsey Global Institute – Sep 2012

Decade of growth – 2000 - 2010

A decade of stable growth

Growing working-age population

Urbanisation – 71% in 2030

The rise of the cities

Not just Java

The rise of the middle class

Education – 42b in 2030, 6% per annum

But what about the risks?

• How is Indonesia currently fairing on:

• - good governance and the consolidation of democracy

• - 2014 elections

• - terrorism and violent extremism

• - communal relations

• - economic management

Good enough to be a dragon

• Indonesia's prospects are sound

• Even just muddling through it is well on track to join China, India, Japan and South Korea as an

Asian dragon

How should we respond?

• We need to reset our mental picture, our grand narrative, of Indonesia

• We need to recognize that not just economic growth but also generational change are transforming outlook, capacities, expectations, and aspirations