Download Alison Smith

Smith 1

A Look Inside the Introvert as a Leader

America has become an upward and outward society: competing, conquering, improving—extroverting. As companies are growing and schools are getting larger, many believe personalities should be getting bigger too. Extroverts, those who are bold, confident, and blessed with the gift of gab, know how to win people over; and as a result, their outgoing and charismatic personalities are assumed to be the perfect fit for leadership positions, as opposed to the cerebral and thoughtful introverted personality. Although stereotypes often label introverts as awkward and improbable leaders, this estimated one-third of the population may be frequently misunderstood and underestimated because of common personality misperceptions, unrecognized value, and forced social functions within schools and work settings.

One of the most culturally accepted beliefs is that all introverts are shy, in fact, many people commonly use the words “introverted” and “shy” interchangeably. Susan Cain, author of the award-winning New York Times best seller “Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That

Can’t Stop Talking,” proposes that “shyness is the fear of social disapproval or humiliation, while introversion is a preference for environments that are not overstimulating” (12). In addition, she explains that although introverts can be shy, most are perfectly friendly, and some are even considered outgoing (12). These non-shy introverts, who are typically referred to as

“socially accessible introverts,” often demonstrate superb leadership skills because they are

“cause-oriented people who are well-trained in negotiating the social arena” (Helgoe 43).

Socially accessible introverts may be hard to distinguish from extroverts because they have strong social skills and enjoy parties, business meetings, and events, but after a while they desire to be home in their pajamas diving into a book. Eleanor Roosevelt, the longest serving first lady in history, is a prime example of a socially accessible introvert. Although her official online

Smith 2

White House biography describes her as “a shy, awkward child,” it further explains that “[she] grew into a woman with great sensitivity to the underprivileged of all creeds, races and nations”

(Black). Unlike most introverts, who are primarily known for their shyness and introverted personality, Roosevelt is acknowledged for holding press conferences, entertaining, giving lectures, and even serving as American spokesman in the United Nations.

Introverts, those who conceal their thoughts and strongly gravitate toward observing others, are commonly identified as unlikely leaders because they are portrayed as antisocial and selfish individuals. Well-known psychologist and author, Laurie Helgoe, disputes this generalization. She insists that “the term antisocial actually refers to sociopathy (or antisocial personality disorder), a condition in which a person lacks a social conscience” (5). Although introverts are often truly concerned about the human condition, they choose to look within for answers, instead of discussing thoughts and problems with neighbors and friends (5). They generally prefer a rich inner life to an expansive social life, enjoy keeping thoughts to themselves, and take immense pleasure in observing the scene around them: people moving about, their dress, and preoccupations. In many cases, when an introvert is thinking about what to eat for lunch or simply observing an individual at a local coffee shop, his silence leaves people assuming that he is antisocial and self-absorbed—when he is thinking, others believe he is judging.

While common stereotypes and personality misperceptions often label introverts as improbable leaders, unrecognized values, like reflection and thoughtfulness can also greatly disguise their ability to thrive as leaders. In a society where “ideal” students and employees are seen as decisive and bold, the extroverts’ ability to plunge into events is strongly encouraged and sometimes even praised. The introverts’ ability to focus on the meaning they make of the events,

Smith 3 however, is exceedingly underestimated. “Introverts gain energy and power through inner reflection, and get more excited by ideas than by external activities,” claims Helgoe (17).

Extroverts, on the other hand, need to recharge when they do not socialize enough. Because they are drawn to external life of people and activities, many assume extroverts are the ones who exhibit exceptional people skills. Despite the general consensus, some introverts demonstrate outstanding people skills. They strive to make personal connections and are drawn to meaningful conversation, not small talk or superficial chitchat. In an interview with The New York Times, self-proclaimed introvert Deborah Dunsire, the president and chief executive of Millennium, a biopharmaceutical company, uses interpersonal skills to her advantage: “in addition to conducting organizational surveys and holding town hall meetings, I schedule walk around time, just stopping by offices. … I would just say, ‘Hey, what is keeping you up nights? What are you working on? What’s most exciting to you right now? Where do you see we can improve?’”

(Bryant). By asking personal, in-depth questions—a technique that introverted leaders utilize exceedingly well—executives like Dr. Dunsire can maintain personal relationships with coworkers and learn what is actually happening within the walls of the organization.

Other essential, yet undervalued qualities that introverts bring to leadership is a willingness to thoroughly listen and an aptness to implement others’ ideas. The powerful integration of attentive listening and critical analysis is extremely important during this age of instant communication; everyone is in such a rush to communicate that many fail to realize the value that can be gleaned from the minds of others. In the Forbes Magazine article, “Why

Introverts Can Make the Best Leaders,” Certified Speaking Professional, Jennifer B. Kahnweiler, describes one successful executive’s listening and implementation skills: “he sits back and listens to his leadership team’s ideas and proposals, often using silence to allow even more thoughts to

Smith 4 bubble up.” Silence like this enables introverts to tune in to team members ideas, and the overall environment. Mike Myatt, the Managing Director at N2growth, one of the world’s top leadership development firms, also encourages silence, as well as a sharing of power in decision-making.

“Astute leaders know there is far more to be gained by surrendering the floor than by dominating it,” proclaims Myatt (“Why Most Leaders Need to Shut Up and Listen”). Leadership is about action. Rather than communicating to message, it is about communicating to engage—to engage in comprehensive listening, feedback, and guidance.

In a society where silence and isolation frequently produce cultural anxiety, many are unaware that introverts prefer work alone, yet it is during this time that they work more accurately, stay on task longer, and give up less easily. We are often so dazzled by the actionoriented, confident, and bold extrovert that we tend to overlook the importance of the quiet part of the creative process. Consider for example, the company Apple. While most people focus on

Steve Jobs’s magnetism and charisma, we often ignore the other crucial figure in Apple’s creation, the introverted engineering wizard, Steve Wozniak. According to the NY Times article,

“Shyness: Evolutionary Tactic,” people like Wozniak are comfortable working in solitary conditions in which they can focus attention inward (Cain). Cain mentions that “Mr. Wozniak describes his creative process as an exercise in solitude. ‘Most inventors and engineers I’ve met are like me,’ writes Wozniak in his autobiography. ‘They’re shy and they live in their heads.

They’re almost like artists. In fact, the very best of them are artists. And artists work best alone

… Not on a committee. Not on a team.’” Introverts become “artists” when working alone because solitude, a catalyst for innovation, powers perseverance through difficult problems and sparks an ability to maintain extreme focus. In fact, Albert Einstein, a consummate introvert admitted, “it’s not that I’m so smart, it’s that I stay with problems longer” (Cain 169).

Smith 5

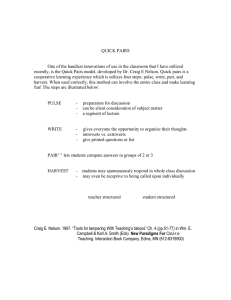

This persistent, go-getter attitude is commonly overlooked because the strong focus of teamwork and collaboration within the typical school setting often leave introverts feeling uncomfortable and nervous. Schools are seemingly designed for the outgoing and sociable extroverts because of the common practice of group thinking, via the method of instructions called “small group” or “cooperative learning” (Cain 77). Cooperative learning, which organizes classroom activities into social learning experiences, has been increasing in popularity throughout the years. In fact, Cain mentions, “according to a 2002 nationwide survey of more than 1,200 fourth and eighth-grade teachers, 55 percent of fourth-grade teachers prefer cooperative learning, compared to only 26 percent who favor teacher-directed formats” (77).

Traditional rows of seating that originally faced the teacher have been substituted for pods of four or more desks pushed together to facilitate numerous group-learning activities. Even subjects like math and writing, which would seem to require individual thought, have been taught as group projects. The school environment, whether it is academic classes dominated by group discussion or noisy and crowded lunch tables, give the introverted child limited time to think, create, and hang out with one or two friends at a time. Instead of preparing them to tackle future leadership roles, the highly unnatural environment leaves introverts feeling unprepared for surviving the school day itself.

Similarly to the school environment, where class discussion and cooperative learning are encouraged through grouped seating, open-office plans foster a highly sociable atmosphere.

While there are some economic reasons for setting up offices this way, the amount of open layouts have been largely increasing because they are believed to produce greater collaboration and innovation. Yet, many studies have found that constant stimulation and social interactions within these offices are highly uncomfortable, especially for introverts. According to The New

Yorker article, “The Open-Office Trap,” organizational psychologist, Matthew Davis,

Smith 6 analyzed more than a hundred studies about office environments in 2011 (Konnikova).

Konnikova indicates that Davis came to a surprising conclusion: “he found that, though open offices often fostered a symbolic sense of organizational mission, making employees feel like part of a more laid-back, innovative enterprise, they were damaging to the workers’ attention spans, productivity, creative thinking, and satisfaction.” This type of setting prohibits introverts from disappearing into private workspaces to focus or to simply be alone. Without a proper environment, most introverts lack their typical creative confidence and exceptional thinking powers, which commonly help aid their potentially valuable leadership abilities.

In a world where the “ideal” students and employees are seen as gregarious, confident, and audacious, introverts are frequently viewed as improbable leaders. Common personality misperceptions, such as the belief that all introverts are shy and self-absorbed, significantly disguise their ability to thrive as leaders. Rather than recognizing their thorough listening skills and ability to maintain extreme concentration, people focus on their quiet demeanor and differing social styles. In school and the workplace, environments where teamwork, collaboration, and constant interaction are encouraged, introverts are often criticized for not speaking up. But, if we let introverts do what they do best—contemplate deeply, away from the crowd and away from any expectations—they could greatly contribute creativity, thoughtful ideas, and valuable solutions untouched by the extroverted society.

Works Cited

Smith 7

Black, Allida. "First Lady Anna Eleanor Roosevelt." The White House . White House Historical

Association, 2009. Web. 27 Mar. 2014. <http://www.whitehouse.gov/>.

Bryant, Adam. "Stepping Out of the Sandbox." The New York Times . New York Times, 29 Aug.

2011. Web. 27 Mar. 2014. <http://www.nytimes.com/>.

Cain, Susan. Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking . New York:

Crown, 2012. Print.

- - -. "Shyness: Evolutionary Tactic?" The New York Times . New York Times, 25 June 2011.

Web. 27 Mar. 2014. <http://www.nytimes.com/>.

Helgoe, Laurie. Introvert Power: Why Your Inner Life Is Your Hidden Strength . Naperville:

Sourcebooks, 2013. Print.

Kahnweiler, Jennifer B. "Why Introverts Can Make the Best Leaders." Forbes . Forbes, 30 Nov.

2014. Web. 27 Mar. 2014. <http://www.forbes.com/>.

Konnikova, Maria. "The Open-Office Trap." The New Yorker . Conde Nast, 1 Aug. 2011. Web.

27 Mar. 2014. <http://www.newyorker.com/>.

Myatt, Mike. "Why Most Leaders Need to Shut Up and Listen." Forbes . Forbes, 9 Feb. 2012.

Web. 27 Mar. 2014. <http://www.forbes.com/>.