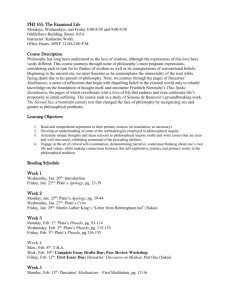

Paul S. Loeb, The Death of Nietzsche's Zarathustra. Cambridge

advertisement

1. Paul S. Loeb, The Death of Nietzsche’s Zarathustra. Cambridge University Press, 2010. xiii + 269pp. ISBN 978-0-521-51923-6 Hardback. 2. Summary (additional, summarizing annotations in the endnotes) In the introduction, entitled “The Clue to the Riddles,” the author announces to offer a radical new understanding of the ground conception of Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, the thought of the eternal recurrence (ER). Loeb proposes to read the Zarathustra as a kind of a Dionysian mystery-cult performance, or a Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk, in which the central message of the main character is performatively enacted in the life-story of this person itself. He asserts that this reading will reveal a fundamental aspect of the thought of ER, which hitherto has been overlooked… Before solving the riddles by this approach, however, Loeb focuses on refuting the most common objections against ER, in particular Simmel’s arguments against the possibility of a numerically or temporally identical repetition.i Against an overwhelming majority of scholars, Loeb argues that an awareness of the recurrence of an event is not contradictory to its being an identical repetition, as if this would make it different from its first or original occurrence.ii In addition, Loeb even argues – on the basis of Nietzsche’s assertion in one of his notes that “between the last moment of consciousness and the first appearance of new life there lies ‘no time’” (KSA 9: 11[38]) – that there is a possibility of having a mnemonic awareness of the previous occurrence of one’s life. The revelation of the thought of ER, by the daimon in GS 341 for example, would refer to the recollection of the moment in which one has died and accordingly, to the prevision of one’s future death.iii Loeb develops his argument in the third chapter by interpreting the gateway-Augenblick in the third part of the Zarathustra as the gateway to Hades and thus, as “a symbol for the last moment of life in which there is revealed a vision of life’s eternal recurrence” (48).iv For Loeb, the dwarf represents the Socratic attitude, which secretly beliefs in the possibility of an escape out of the eternal cycle of life.v Zarathustra pulls him away, however, from his ‘view from nowhere’, back to a temporal perspective, from where the reality of circular time can be truly acknowledged (55). Meanwhile, Zarathustra previsions himself crossing the gateway, which represents the moment of death and the moment of rebirth at the same time (since there lies ‘no time’ between them),vi by way of his ability to recollect the moment of his previous death and rebirth. In contrast to Socrates, who manipulated others to bring about his death out of disgust with life, Zarathustra eventually chooses his own death, towards the end of part III, out of overfullness, in order to become empty and to be refilled again (76-7).vii Chapter four and five together form a kind of parenthesis, in which Loeb interprets the fourth part of the Zarathustra as an “internally analeptic satyr-play.”viii Chronologically, Loeb argues, this part falls somewhere between the “Tables” and the “Convalescent” chapter in part III, ix or more specifically, in the “implicit chronological gap between the remarks in the third and sixth sections of the “Tablets” chapter” (125).x In this part, Zarathustra’s fulfillment of his task is parodically dramatized according to the Biblical scheme of the passion of Christ: noon crucifixion, (seventh-day) convalescence, last temptation and third-day resurrection (101-117). xi In the following chapters, Loeb continues his argument by connecting the dwarf, as a symbol for the eternally recurring small man, with the image of the black serpent in the subsequent vision-riddle.xii Accordingly, the biting off the serpent’s head represents the decision to put to a halt the ongoing presence of the small man by installing the thought of ER as a selective principle. In contrast to the inability of the small man to bear it, Zarathustra is able to take on the knowledge that “his life is a closed circle” in order to “will backward” and overcome the spirit of revenge, by: 1) Realizing that his past is partly a result of his present and future willing (“reconciliation”), and 2) Transmitting mnemonic information to his younger self’s subconsciousness (“a power over time that is higher than all reconciliation”) (186-7). xiii 1 In this way, Zarathustra “becomes the artist-creator (Dichter) of his own life, because he is able to backward-will his completion and perfection into his past so as to guarantee its fully affirmable unity, meaning and necessity,” according to Loeb (189). However, although Zarathustra reaches the child phase,xiv and becomes ‘no-longer human’, he is not yet a superhuman, but rather the firstling among those who sacrifice themselves for the sake of the superhuman, teaching others – retroactively, i.e. via his younger self – to do so as well (201-4).xv 3. Characterization This book, which resulted from, or – as the author clarifies in the Preface – into at least ten published articles in the last decade, offers a clear and careful examination of the main passages on ER, contextualized within an overall interpretation of the structure and message of Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Every chapter concludes with a short summary, which provides a clear overview of the argument as given till thus far. Although Loeb’s interpretation is highly controversial, his reading of the passages in the Zarathustra is rather rich, and at times, quite illuminating. Moreover, he takes into account almost all of the previous literature on ER, as well as the most important commentaries on the Zarathustra, which he reviews fairly and thoroughly. Although he mainly focuses on the Anglophone scholarship (including its “consensus”), Loeb has taken the effort to include German works as well, amongst others, Günter Abel’s important study on the thought of ER (1984; 1998), Heidegger’s two volumes on Nietzsche (1961) and Zittel’s commentary on the Zarathustra (2000). For the primary sources, Loeb generally uses the Hollingdale-Kaufman translations, together with the German critical edition (KSA/KSB/KGW). 4. Evaluation From the above summary, it should become clear that Loeb offers a renewing, though controversial, and at times quite bizarre reading of the Zarathustra and its ground conception, the thought of ER. It must be said, however, before going into his central arguments, that Loeb’s careful and stringent textual analysis of many key passages in relation to the thought of ER offers many valuable suggestions and possible allusions, which at the least could contain some truth. For example the contrast with Socrates’ attitude towards life and death in the aphorism before GS 341 (which is not to say that GS 341 is only about the moment of death); reading part IV of the Zarathustra as a satyr play (though not necessarily chronologically situated within the “Tablets” chapter); and the connection between the figure of the dwarf and the image of the black serpent, based upon the allusion to Wagner’s Siegfried (cf. also endnotes iii, iv, viii, ix,xi, xii). Moreover, as Loeb himself points out, the cost of his controversial interpretation, namely that it attributes “to Nietzsche views so radical and implausible that they would seem to violate the principle of interpretive charity” (170), is not in itself a sufficient argument against this interpretation (though I would contend that this interpretation would certainly harm Nietzsche’s credibility as a philosopher). Nevertheless, although it is not possible to evaluate and to do justice to the numerous, accumulative text-based arguments that Loeb gives for many of his interpretations, I think that the central argument for his overall interpretation lacks persuasive power on the most crucial points: First of all, against Loeb’s insistence that Zarathustra dies towards the end of part III, we could bring in that he misuses Nietzsche’s remark in one of his letters to his sister Elisabeth, to make this argument. In this remark, which is also the motto of Loeb’s book, Nietzsche states that he “must help [his] son Zarathustra to get his beautiful death,” in order stop thinking about it (KSB 6, 557). It must be noted, however, that Nietzsche wrote this letter after he finished the third and a substantial piece of the fourth part (November 15, 1884). This implies that if he wanted Zarathustra to die indeed, it had to happen in the never-written, subsequent parts. And as it turns out, Nietzsche writes this indeed with regard to the “from now on inevitable fifth and sixth part” (later on designed as yet another, separate Zarathustra-book under the title Mittag und Ewigkeit (KSA 13,282)), in which the death of Zarathustra was presumably supposed to take place. Finally, I find Loeb’s explanation that on his reading, “Nietzsche means that he feels the need to write in more detail about the events that 2 lead up to the beautiful death that he has already depicted at the end of part III,” incredible, and insufficient as an explanation for his thesis that Zarathustra dies at the end of the third part (cf. 115 fn. 66). Secondly, and in connection with this, also Loeb’s argument that part IV chronologically falls within the ‘Tablets’ chapter of part III, is not convincing. As apparently Robert Gooding-Williams has pointed out to him (cf. 101, fn. 36), the fourth part starts “months and years” after its prequel (whatever it may be), while the ‘Convalescent’-chapter in the third part starts “not long after [Zarathustra’s] return to his hole,” presumably referring to Zarathustra’s heimkehr to his hole and his animals, just before the ‘Heimkehr’-chapter (‘On Apostates’, 2). Loeb wants us to belief, however, that the “not long after his return to his hole” in the ‘Convalescent’-chapter alludes to “the narrator’s announcement, at the very end of Part IV, that Zarathustra left his cave (…).” This is not convincing at all, since, first of all, it would imply that Nietzsche only filled in this missing, though indispensible chronological link retrospectively and kept it, moreover, privately (as the fourth part was only printed in private).xvi Secondly, the concerning action moves into the opposite direction (leaving the cave) than the movement that is described by the concerning reference (returning to the cave). Not only is Loeb’s argument for the chronological placement of part IV within part III inconsistent, its rebuttal totally undermines his claim that Zarathustra dies towards the end of part III (unless one assumes a physical resurrection, or takes the “months and years” to refer to Zarathustra’s rebirth, of course). Thirdly, Loeb’s main argument for the possibility of transmitting information from one life-time to one’s recurring self in another life-time is based upon Nietzsche’s remark, in one of his notes, that “between the last moment of consciousness and the first appearance of new life there lies ‘no time’” (27; KSA 9: 11[38]). According to Loeb, this presupposes not only that Nietzsche rejects the existence of any absolute or universal time, i.e. a time that exists independently from the succession of things, but also that time is strictly perspectival, i.e. “that the observation of time’s passing depends upon some particular perspective or frame of reference” (27). Accordingly, the observation or experience of time of one particular consciousness is no less correct than any other. And from the perspective of one particular consciousness, time can only exist as long as this consciousness is operative. Accordingly, Loeb argues, “from my perspective there can never be any end or any sort of break in my life: my dying consciousness is immediately succeeded by my returned awakening consciousness” (ibid.). This conception of perspectival time implies, according to Loeb, that among my numerically distinct selves there are “substantial psychological,” as well as “interesting epistemic” relations, which are the source of mnemonic, and thus “precognitive” knowledge (28). It also enables me, according to Loeb, to “impress into my memory messages that will be buried in my younger self’ subconscious and that will manifest themselves in the form of precognitive dreams, visions, omens and voices” (ibid.). Loeb’s derivation of what would be a rather bizarre position, largely on the basis of one particular note of Nietzsche, is rather blunt and clearly fallacious, although it touches upon some problematic issues with regard to Nietzsche’s view of time. xvii It is right – and this seems to be Nietzsche’s point in the particular note – that from the perspective of one particular consciousness, the observation of time only lasts as long as this consciousness is operative, and from this perspective, time proceeds in an continuous circular flow, just as the recurring consciousness itself can be said to exist only as long as this consciousness is operative, and in this regard, to constitute a circle in itself.xviii This does obviously not imply, however, that there is any direct causal connection – either psychological or epistemic – between the moment in which a consciousness stops working and the moment in which it emerges again, whether it be from a first or a third person perspective. Also the indications, which Loeb finds in GS 341 and throughout the Zarathustra, for the performative enactment of such mnemonic transmittances of information in the form of “backward-willed communication” are not convincing, let alone persuasive (cf. endnote xiii). Finally, possibly the most crucial objection is that Loeb’s reading of the ER does not contribute anything to a solution of the problem of the reconciliation with the past. For, as Loeb himself admits, 3 the ability to influence the past by way of his present and future willing, does not change anything to its irreversibility, since it will always run in exactly the same manner (186). The only thing that changes is the realization that the past is in fact partly a result of one’s present and future willing, which enables one to reconcile with it, and in addition, to will it backwardly, by sending mnemonic messages to one’s younger self in order to create one’s past self into the perfected self who one now is. “From the standpoint of the moment in which [one] has perfected [oneself],” Loeb argues, “[one] is able to will into being the very past that has enabled [one] to become who [one] is” (189). However, it is not clear at all in what way the mnemonic messages are necessary for this retroactive self-perfection, or how they contribute to it. What does the information, that part of what enables my past self to become who I am is coming from my present or future self, contribute to a reconciliation with this very past? Does it not make a possible reconciliation with the past even harder, since it shows that even in spite of my ability to exert an influence upon it, the unwanted aspects of the past will not be changed? We may conclude then, that despite the high scholarly level of this work, it lacks any persuasive arguments for its daring, though implausible thesis on the most crucial points, but is nevertheless worthwhile to read in order to gain a richer understanding of the multi layered text of Zarathustra. Wolter Hartog 20-12-2010 i Loeb argues that “it remains a scandal to Nietzsche scholarship that we are obliged to assume the centrality of his doctrine of eternal recurrence but we are not able to give a satisfactory reply to anyone who may claim to refute this doctrine” (11), seemingly suggesting that in order to study a particular philosopher one needs to be convinced by his whole thought and to agree with every argument, which obviously is a rather strange premise. ii After all, if it has already occurred an infinite amount of times and will occur again infinite times, there obviously is no such initial or original occurrence. iii In order to make this argument, Loeb particularly draws upon the connection with the previous aphorism, 340, in which Socrates’ death is discussed, as well as the next aphorism, 342, in which, according to Loeb, the death of Zarathustra is already announced. Other clues that GS 341 is about death and dying words, he finds in the fact that it is supposed to happen in some day or night, “an odd vagueness that may well refer to the idea that death can come at any time” (34). Secondly, the demon does not refer to the life that the addressed still has to live. On the other hand, the demon does indicate that the addressed will have to live it again. Fourthly, the turning of the hourglass refers to death and rebirth. Finally, the demon’s closing remark to the “last eternal confirmation and seal” refers back to Socrates’ last judgment. In contrasting the diagnostic test, which discerns if one has “become good to life,” with the final moment of Socrates, which reveals how much he suffered from life, Nietzsche refutes Plato’s depiction of Socrates in his Phaedo as a good Dionysian, accusing him to have corrupted the Dionysian doctrine by allowing the possibility of escape from the cycle of eternal rebirth (39-40). Finally, an additional clue for interpreting the moment of revelation in connection with the moment of death, is Nietzsche’s allusion to the last moment of Goethe’s Faust, which is at the same time his highest moment (der höchsten Augenblick) (43). iv Again, Loeb gives a whole lot of arguments to support his interpretation: the allusions back to GS 340-2, amongst others by the word Augenblick. Furthermore, the use of “poetic death-imagery” throughout the Zarathustra – his descent into the underworld, for example – and in the passage on the gateway in particular, in which he creates a similar atmosphere as in GS 341: solitude, silence, whispering, spider, moonlight, etc. v Loeb takes into account Robin Small’s finding that the dwarf’s response seems to be inspired literally by a passage out of Gustav Teichmüller’s Darwinismus und philosophie, but he argues, contrary to Small, that the dwarf does not really believe that “time is a circle,” whereas Zarathustra does. vi The most explicit indication for this, according to Loeb, is the reference to the sudden shift in vision after crossing the gateway and the subsequent childhood memories that coming up (65-7). 4 vii The story of Zarathustra in general functions as a counter-myth over against Plato’s story of the death of Socrates in order to enact a “world-historic agon between the dying Socrates and the dying Zarathustra,” according to Loeb (83). viii Loeb relates to an early notes in which Nietzsche comments on the Dionysian festivals, consisting in its heyday in four parts, a trilogy of tragedies, followed by a more cheerful, satyr drama based on the same mythological material (KSA 7:1[109]). In the same way, the first three parts of the Zarathustra end with a tragic note, while part IV ends happily (91-2). The chorus of dancing, singing higher men in Part IV also seems to be built upon the model of the Greek satyr chorus Nietzsche talks about in BT 7-8. Whereas Nietzsche wished that the Parsifal had been intended as a satyr play to the three-part Ring, he has designed such a satyr play for his own Zarathustra in order to demonstrate his artistic triumph by laughing at himself and seeing himself and his art beneath him (cf. GM III, 3). In contrast to deflationary or ironic readings (Nehamas), however, Loeb argues that the analeptic satyr play only functions to “supplement, clarify, and expand certain dramatic and philosophical events that had already taken place in the published Parts I-III” (90). It is “internally analeptic,” because it chronologically falls within the first three parts, more specifically, the end of part III (94). ix In first instance, Loeb argues that part IV must chronologically precede the end of part III, since part III is clearly intended as the book’s (chronological) ending (terminus ante quem), as the allusion to the seven days of creation in the last section of part III (13:2) suggests that Zarathustra’s work is completed (90). Secondly, the conclusion of part IV cannot be pushed back past the “Tablets”-chapter of part III (terminus a quo), since at the beginning of this chapter, Zarathustra is still waiting for the sign (of the laughing lion with the flock of doves, the lion referring to the needed lion’s spirit, the doves to the silent arrival of the most abysmal thought and a symbol of Zarathustra’s returning disciples) that his hour has come, while throughout part IV, Zarathustra is still waiting and ripening up to its end. As part IV ends with the lions-and-doves sign, it must precede again the “Convalescent” chapter, in which Zarathustra is found to be ready to summon up his most abysmal thought and announces the arising of the great noon (99-100). This is chronologically followed by the summoning of the most abysmal thought at the beginning of the “Convalescent”-chapter (101). Other clues for the suggestion that Nietzsche “intended the drama related in Part IV to chronologically precede and introduce the climactic opening of the “Convalescent chapter:” In Part IV Nietzsche overcomes the temptation of pitying the higher men’s for their suffering from nausea and self-contempt, by his own great nausea induced by their revealed smallness, which according to Loeb, “leads into, and prepares the way for “his Part III overcoming of the nausea induced by even the highest man” (109-10). Part IV ends with Zarathustra’s acknowledgement that the further pursuit of his task wil bring him much suffering and unhappiness (IV.20), which shows that he his prepared to confront his most abysmal thought at the end of Part III. Part IV depicts Nietzsche as a shepherd, finding, gathering, and feeding the higher men, while the vision-riddle of the serpent and the shepherd predicts that Zarathustra will be no longer a shepherd after spitting out his nausea (111). The ‘Noon’-chapter in Part IV describes similar experiences as the ones Zarathustra has after awakening his most abysmal thought, but the former are not quit yet fully ripe (111-2). The allusion to the last supper by Nietzsche’s description of Zarathustra’s long meal with the higher men at the end of Part IV as “das Abendmahl” must chronologically precede the allusion to the crucifixion in Zarathustra’s description of his nausea as a crucifixion (112) (cf. next endnote). Zarathustra commands his thought in “The Convalescent,” once it is first awaken, to “stay awake eternally for” him, while in the fourth part, the thought is still asleep and hidden (112-3). At the end of the third part, Zarathustra stops speaking to his animals and forgets them, while at the beginning of the fourth part, he jokes and chats with them (113). Towards the end of part IV, Zarathustra describes himself as “one prepared to fly,” while in his last words in Part III, he describes himself as a bird that is actually flying (113). Finally, a plot in which Nietzsche resurrects Zarathustra metaphorically suits well the traditional function of a satyr-play and even that of a “fifth Gospel” (KSB 6, 327) (114-6). Nietzsche constructed 5 “an implicit temporal, dramatic and philosophical ellipsis that can be filled in after he has written the conclusion of Zarathustra’s tragic Untergang,” according to Loeb (114). “Since the time of this chronological gap is indefinite (lasting “months and years”), and since part IV fills in only three days of this time, Nietzsche leaves himself room to write further analepses and to supplement further dramatic and philosophical events – perhaps the ones outlined in his unrealized plans for two additional Zarathustra parts” (115). x In the subsequent chapter, Loeb continues his argument by proposing “more specifically that Nietzsche’s analeptic satyr play relates events that belong in the implicit chronological gap between the remarks in the third and sixth sections of the ‘Tablets’ chapter” (125). Part IV deals, according to him, for a great deal with Zarathustra’s relation to his disciples, with whom he does not reunite before the end of part IV. Nevertheless, Zarathustra seems to be addressing his “brothers” in the ‘Tablets’ chapter, while he last saw them at the end of part II (II.22). Accordingly, Loeb argues that the second reunion of Zarathustra and his disciples, together with the anticipated great-noon celebration, must have taken place during the speeches in the ‘Tablets’-chapters. Whereas in the end of Part IV, Zarathustra is likened to a an emerging morning sun, it is still Zarathustra’s morning when he is reunited with his disciples in the ‘Tablets’-chapter, and where he summons a selected few, his first-borns, to sacrifice themselves for the sake of a single unified humankind with a single common goal (130). xi Loeb argues that Zarathustra describes himself as a “cross-bearer (Kreuzträger), compares his experience to a crucifixion (Kreuzigung),” but it is obviously quite doubtful whether these terms, only mentioned once in “The Convalescent,” are applicable to Zarathustra himself (cf. 103). Other parallels between Christ’s passion story and Zarathustra’s fateful task, like for example the allusion to the earthquake (die Erde bebte und brauch) in “The Seven Seals” are more convincing (103-105). xii On the basis of a supposed allusion to Siegfried’s slaying of the Schlangenwurm (Fafner) and the “mole-like dwarf” (Mime) in the second act of Wagner’s Siegfried. Cf. Paul S. Loeb, “The Dwarf, the Dragon, and the Ring of Eternal Recurrence: a Wagnerian Key to the Riddle Nietzsche's Zarathustra,” Nietzsche-Studien 31 (2002): 91-113. xiii These “backward-willed communications” to Zarathustra’s younger self are noticeable in, for example: the dream of (the younger) Zarathustra at the beginning of the second part of a child holding up a mirror in which a mocking laughing devil represents his enemies’ distortion of his teaching (Z. II,1). According to Loeb, “Zarathustra’s redeemed child-spirited soul has backward-willed him a warning that keeps him from losing his disciples and his destiny” (194); Later on, Zarathustra hears a voice saying “It is time! It is high time,” coming, according to Loeb, from “his future redeemed soul letting him know that he must soon leave his children in order to prepare for the great-noon event of summoning up his most abysmal thought” (ibid.); At the end of Part II, Zarathustra dreams of his mistress, the stillest hour, who tells him without voice that he must become a child and that it is therefore time to leave his children (II.22, III.3). According to Loeb’s reading, it is Zarathustra’s future redeemed soul who, having become a child, instructs him on how to gain precisely his future redemption (195); The fact that Zarathustra is still carrying within his subconscious the buried mnemonic messages his “dead” self, functioning as a conscience that keeps him focused on his ultimate goal, is prefigured in the image of Zarathustra carrying a dead companion on his back, in the preface of the Zarathustra. The most explicit visit from Zarathustra’s own “afterlife,” however, can be found in another riddle in the second part, in which a wind rears open the gate of the fortress of death and throws up a black coffin that bursts open with a thousand peals of child’s-laughter that liberate Zarathustra (II.19). According to Loeb, “Zarathustra rejects the disciple’s interpretation of this dream, because he knows that his various dream-symbols do not refer to the power of his current self, but rather to the power of his redeemed “dead” self.” This is supported, according to him, ‘by Nietzsche’s image of the redeeming Zarathustra as a blustering wind liberating the will from its imprisonment in the past (II.19, 20, III.12:16); by his allusion to Zarathustra’s post-redemptive description of himself as a mocking gust sweeping into old tomb chambers and bursting tombs (III.16.2); and by his allusion to the postredemptive, wicked, gravity-killing laughter of his child-spirited soul (III.2:2, III.16:3, 6)” (195-6). 6 xiv His knowledge of the ER and his ability to “will backwards” enable Zarathustra “to create a new soul that possess al the traits that he earlier attributed to the child-spirit:” 1) free from the immovable “it was,” he becomes a playful, child- and birdlike spirit, 2) his ability to backward-will necessity, meaning and unity into his life enables him to play dice on the earth, like Heraclitus’ “great child,” 3) it also enables him to say “yes” to his life and self, 4) because guilt flows from the immovable “it was,” Zarathustra is freed from it, which in turn makes him long after life’s ER again (196-8). xv The final chapter is dedicated to showing – against the “scholarly consensus” that the main thoughts of Zarathustra are outdated by the post-Zarathustra writings, which are more important and mature – that his interpretation of the Zarathustra is supported by the Genealogy, in particular the latter’s account of memory and the announcement at the end of the second essay. xvi This would also contradict Loeb’s claim further on that “Nietzsche wrote and published parts I-III so that it could be read as a self-contained book” and that this does not mean that Part IV “is required in order to understand” parts I-III (109, fn. 52). xvii The issue does raise the question of whether time is strictly subjective – whether it be in a perspectival or in a more transcendental sense – or whether Nietzsche also leaves room for a kind of real, objective time, independent from subjective experience. As some authors, among whom Small and Stegmaier, have shown, there are some notes that clearly suggest the latter. Cf. e.g. KSA 9:11[184] xviii Although the image of a circle is already problematic here, as Robin Small points out, since it rules out any beginning or end, whereas the circle of a recurring life-time must be considered as broken through by the radical event of death and (re-)birth. Cf. Small, Time and Becoming in Nietzsche’s Thought, 163. 7