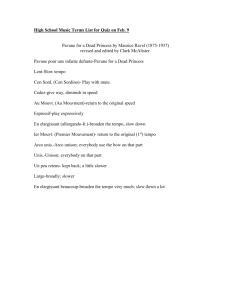

Interpreting Music, or what written music won't tell you This is an

advertisement

Interpreting Music, or what written music won’t tell you This is an extra "Musical Note" on a topic I've been asked about more than once, namely the way to interpret orchestral (and other) music in terms of its phrasing and expression. This covers note lengths, particularly at the end of phrases and also dynamics: how long is long, how quiet is quiet? Although tempo is an important element in this mix, it's a variable under the conductor's control, so I won't include it in this brief article. Note Lengths If you read a text book about musical notation, it will tell you that a quaver is half the length of a crotchet and a crotchet with a dot after it is equal to one-and-a-half crotchets. It may also tell you that a quaver - half a crotchet -followed by a quaver rest is the same as a crotchet with a dot over it. This provides the basis for the points I want to make. The first is that music, as written, with its crotchets, quavers, dots and rests, etc., is a guide to how it should be played, "guide" being the important word. If you ask a computer to play a piece of music and it slavishly follows the theoretical rules of the notation, the result sounds lifeless and mechanical. It contains no expression. The expression finds its way into the music with how those notes, dots and rests are interpreted. "Phrasing" means the process of dividing the music up into meaningful chunks; phrasing is a good word because it means the same when applied to language and the written word. In music, its phrases can vary in length. A phrase is usually characterised by having a short breathing space at its end to separate it from the next - the equivalent of a comma or semicolon. That breathing space will often not be clear from looking at the musical notation. It needs to be made clear by the musician's interpretation of that notation. There is a term in music, "phrasing off", which means creating that breathing space found at the end of a phrase. In addition, though, phrasing off can be applied to individual notes, even to whole series of notes. Imagine a series of crotchets played at a fairly slow tempo. Phrasing them off means creating a breathing space between each one and this is achieved with a diminuendo applied to each note. At the beginning of the note it is played at the indicated dynamic, which might be, for example, forte or mezzoforte. However, the process of phrasing off means that the end of the note should be pianissimo or even pianissississimo (pppp!). Tempo Considerations The degree to which small musical units might be phrased off depends on the tempo. In general, at a slow tempo the effect can be increased, whereas at a quick tempo it might be inappropriate. (As an aside, the marking vivace is not an indication of tempo. It is usually taken as meaning pretty fast, but it is really an indication of style not speed, meaning "lively".) Don't think that phrasing off applies all the time. There may even be notation to indicate that it should not be done, such as sostenuto. Consider your crotchet with a dot over it: at a slow tempo, this would suggest phrasing it off and applying a diminuendo to each note, but at a quick tempo, it would be appropriate to play it as a shortened note, more like a quaver plus quaver rest. A quaver plus quaver rest at a slow tempo would suggest a definite gap between notes, but each quaver should have its full value as a genuine quaver. At a quick tempo, the way to play this note would be as a clipped spiccato. Dynamic Considerations When you play in a group of musicians, it is often difficult to hear yourself above the others and the temptation is consequently to play louder. The effect is that an orchestra's default dynamic range will be somewhere between mezzoforte and forte. Fortunately, especially for string players, it is a lot easier to play quietly as much less physical effort and movement is involved - lighter bows and shorter bow strokes are required. So, if the instinct to play louder to hear oneself can be overcome, the effect is to create the availability of a much wider dynamic range and this is vital for putting expression into the music and into its phrasing. A surprising side effect is that when you play quietly, as long as everyone else is doing so, too, you will hear the sound you are creating much more clearly. One final point, putting expression into playing music requires not only movement of fingers, hands and arms, it requires movement and flexibility in the whole body. Watch a pro. orchestra swaying around as they play and you'll see what I mean. Good luck! Bill Anderton