Women and Non-Violent Protests

advertisement

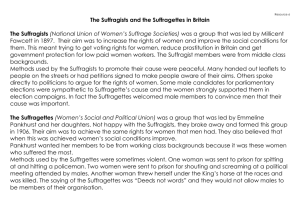

Women and Non-Violent Protests Presenter: Charli Roach Overview • The participation of women in non-violent resistance and protest is not geographically or chronologically distinct, and as such examples can be found in a variety of localities and eras. • The motivations for women to become involved differ, from the political and ideological convictions of the suffragettes and the Greenham Common protestors to the emotional compulsions of the Rosenstrasse wives and Argentinian mothers. • Women have also played a part in many of the movements that are now synonymous with non-violence, such as the Civil Rights Movement in America, so it must be noted that they are not solely concerned with ‘female’ issues or familial concerns. • It has been contended that most the stories of women in the development and use of non-violence have been hidden or underrepresented in histories (McAllister). Key question – Does gender make a difference to how people embrace and practice non-violence? • Carol Flinders: Aung San Suu Kyi ‘…the heroes and heroines of nonviolence have a fine way of transcending conventional gender scripts altogether.’ The Science Behind It! • Scientists from the UCLA claim to have discovered that men and women react differently in the face of a perceived threat: Men – ‘fight or flight’ Women – ‘tend and befriend’ (meaning that they feed the children, calm everyone down and try to defuse the tension) • • As such, they have concluded that a woman will fight to defend her loved ones but only when all the other options have failed. This research does however seem to have been undertaken from a very traditional viewpoint and does not consider female involvement in ideologically or politically motivated resistance or protests. The British Suffrage Movement The Origins of the Suffragist Movements • Female suffrage - emerged as a political issue in Britain in the 1860s following Parliament’s refusal to replace ‘man’ with person in what would become the 1867 Reform Act bill. • 19th century: loose groupings of suffragists drawing on ideas and members from other campaigns, such as the Chartists and the Abolitionists – no dominant individuals or groups until the turn of the century. • Trans-national movement, sought to redress the social injustice of male repression. • British society – support for the idea that suffragism was a mental disorder ‘akin to epidemic hysteria, with its attendant symptoms of a loss of the normal sense of decency and of the normal use of reasoning powers’. • Edward VII’s surgeon: ‘sexually embittered women’ who were clearly ‘life-long strangers to joy’. Levels of Violence • In Britain and America, the movement involved a number of non-violent techniques; rallies, petitions, mass movements, lobbying and fasting. • The suffragists were also characterised, especially by the eve of the First World War, as highly organised and very articulate. • But - inaccurate to claim that the suffrage movement was a non-violent one because it was far from homogenous, especially in Britain where two separate strands of suffragists emerged; the constitutionalists and the militants, who existed along a continuum from those who believed they must resist passively to those who felt that terrorism was both justifiable and functional. The NUWSS • 1897, National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies by Millicent Fawcett - grew to have over 50, 000 members. • Adherents of peaceful protest - pragmatic rather than ideological as she thought that violent behaviour would only fuel traditional notions that women were too irrational to be worthy of suffrage. • Strategy - the patient use of logical arguments to gain the vote. Argued that if women were bound by laws, surely they should have a say in their making. And women even employed men who could vote when they could not! • Very slow progress – converted some but the predominant feeling was still that women would not be able to understand the workings of Parliament. The WSPU • 1903, Women’s Social and Political Union founded by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters, Christabel and Sylvia. The Union’s members became known as the Suffragettes - not prepared to be patient, willing to use violence. • Peaceful until 1905, Christabel and Annie Kenney arrested for interrupting a political meeting. They refused to pay a fine, preferring a prison sentence to highlight the injustice that was being done to them. Emmeline Pankhurst’s autobiography: ‘..this was the beginning of a campaign the like of which was never known in England, or for that matter in any other country…we interrupted a great many meetings…and we were violently thrown out and insulted. Often we were painfully bruised and hurt.’ • • Violence committed by the WSPU members – burned down churches (CofE opposed to their appeals), planted a bomb in Westminster Abbey, vandalised Oxford Street shops and golf courses, firebombed the homes of politicians and sailed down the Thames hurling abuse at Parliament. Also used some non-violent measures however, such as refusing to pay taxes, chaining themselves to Buckingham Palace and welcoming arrests. The ‘Cat-and-Mouse’ Act • Hunger strikes in prisons responded to by force-feeding - huge public outcry as this was traditionally meted out to lunatics rather than educated women. • 1913 the ‘Cat-and-Mouse’ Act was introduced, which ordered that hunger-strikers should be released when they fell ill and re-arrested once they had recovered sufficient strength. • If these women did not recover and instead died whilst on release then the government was able to exonerate itself from any blame or embarrassment. Their weakened state also meant that they could not engage in any violent activities whilst on release, so it provided the government with a very powerful weapon against the suffragettes. • Edgar Holt: ‘it was an effective measure… and there were no more deaths from hunger strikes until 1920’. State Response • Evidence of their movements – Scotland Yard ordered a camera lens to carry out the first secret surveillance photography in Britain against the Suffragists. Also, attended meetings and kept detailed notes on them. • 1871 – became policy for all inmates to be photographed in prison, but civil disobedience continued by refusing to have their photographs taken, so they were either captured surreptitiously whilst exercising or forcibly held in front of the lens. Public Response • 1913 – movement gained it’s first real martyr when Emily Davison threw herself under the king’s horse during the Epsom Derby. This was however quite counter-productive – if this is what an educated woman does, surely no women should be allowed to vote? • Most photographs issued in the press however showed police and mob brutality which increased public sympathy. • Central to non-violence is an awareness that brutal repression can produce opposition to their opponents. Suffragists realised that they were gaining more than they were losing due to these incidents generating sympathy. Then deliberately tried to incite violent reprisals in order to unease and embarrass their opponents and encourage them to grant them their demands. World War One and the Extension of the Franchise • It is arguable that, had it not been for the First World War, the violent actions of the militant suffragists might have escalated even further (February 1913, blew up part of David Lloyd George’s house – a man who was widely considered to be a supporter of women’s rights). • But when war broke out break out, Pankhurst and Fawcett told their members to cease their campaigns and lend their full support to the war effort and the government. • Certain groups did continue campaigning but far less publicly and often carried out war-work simultaneously. • 1918, ‘Representation of the People Act’ extended the franchise to certain women – result of campaigns or the work done by women during the war years? The Mothers of the Disappeared in Argentina The Origins of the Movement • Human rights groups claim that between the coup of 1976 and 1983, 30,000 people were killed under military rule in Argentina in what became known as the Dirty War. • In the years following the coup, sons and daughters began to disappear ‘if they raised their fists, raised their voices, raised their eyebrows’ (McAllister). • The families were then left with no news, good or bad, about the whereabouts of their children, so went daily to the Ministry of the Interior in Buenos Aires to try to get information. • Eventually, these women were each informed that their case was being ‘processed’. The Founding of the Movement • Azucena de Vicenti decided that they should instead convene outside, on the Plazo de Mayo, where the world could see them. • April 13 1977 - fourteen women gathered together in an illegal public demonstrations, which went largely unnoticed due to the day chosen (Saturday). • Thursday afternoons were selected for their protests and, on these days, increasing numbers of women walked slowly in a circle carrying pictures of their missing children. Publicity and Repression • 5 October 1977, the women raised the funds to buy an advertisement that appeared in La Prensa. This advert featured the pictures of 237 ‘disappeared’ next to their mother’s names and carried the headline ‘We Do Not Ask for Anything More than the Truth’. • Ten days later several-hundred women brought a petition to congress bearing 24, 000 signatures. • Harsh and repressive state response – harassment and arrests of women and foreign journalists. • However, the mothers continued to visibly protest every Thursday in large numbers and held open meetings, to which grieving relatives could come for information and support. The Silencing of the Movement • Meetings infiltrated by‘Gustavo’, (Alfredo Astiz), who led the women into a trap after befriending them. • December 1977, nine women leaving a meeting ‘disappeared’ just before another advertisement was released. Two days later another three women were to vanish, including one of the founders Azucena De Vicenti. • Real impact on the movement – the following Thursday only forty women came to the Plaza and when the movement called a press conference only four foreign journalists dared to attend. • 1978/ early 1979 - the protests with much smaller numbers and weekly arrests. • Women still met in the sanctuary of churches, where notes were passed and decisions made in silence. Re-emergence • May 1979, the women re-emerged with with much greater organisation – decided to formalise their structure, hold elections, become legally registered as an organisation and to open a bank account to store the funds that had been coming to them from international supporters. • Offices rented and the ‘House of the Mothers’ established, published their own bulletin from these facilities. • Resumed their weekly marches at the Plaza - wore flat shoes and white scarves to symbolise the blankets of the lost children. Photos carried and mega-phones used to broadcast individual stories to the people in the streets. • Cruel police repression continued but the women were now more organised and determined so remained both courageous and visible, attracting yet more support and sympathy to their cause. Legacy • 26 January 2006, final March of Resistance - no longer considered the government to be hostile to their crusade. Weekly silent vigils continued however. • Other South American women have followed their lead and they have also been credited with causing political change in Argentina. • The military has admitted that over 9,000 of those kidnapped are still unaccounted for, but the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo say that the number is closer to 30,000. Of these, it is believed that around 500 were adopted by military-related families and that the others were killed (numbers hard to determine due to secrecy). • The Mothers’ have now established an independent university, a bookstore, a library and a cultural centre; facilities that provide subsidised and free education, healthcare and other services to the public and students. Additional Case Studies The following examples provide additional case studies for female participation in non-violent resistance: •The Women in Black in Israel and Serbia •The Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp •The Rosenstrasse in Germany, who successfully protested against the detention of their Jewish husbands in Nazi Berlin Rosenstrasse Final Topic for Debate - Are women inherently more suited to non-violent resistance than men? M.K. Gandhi, Young India, 10 April 1930: ‘ To call women the weaker sex is a libel; it is man's injustice to woman. If by strength is meant brute strength, then, indeed, is woman less brute than man. If by strength is meant moral power, then woman is immeasurably man's superior. Has she not greater intuition, is she not more self-sacrificing, has she not greater powers of endurance, has she not greater moral courage? Without her man could not be. If non-violence is the law of our being, the future is with women. Who can make a more effective appeal to the heart than woman?’ Gandhi’s Attitude Towards Women • Gandhi believed that women had a great moral purity and tolerance for enduring pain, apparently making them ideal candidates for his satyagraha • However, he was also a traditionalist and wanted women to keep spinning and leave the lawbreaking to the men. • He did later relent on this stance after the women inspired by him to participate in civil disobedience complained about this exclusion. Non-violence and the ‘Bubble’ • Gandhi stated that he had learnt non-violence from his wife Kasturb, who behaved like a traditional Hindu wife; gentle, patient, loving yet able to resist his ‘petty tyrannies’. • As such, is non-violence inherently more suited to women or does it acquire an additional potency when men act against centuries of societal conditioning and denounce violence? • One theory: men have to renounce violence whilst women often are actually stepping out from a safe environment to participate in non-violence (Flinders - ‘From ‘Bubble’ to Action’). Questions for Discussion • Are women particularly suited to non-violent resistance and, if so, why? • With female non-violence, to what extent has emotional appeal outweighed rational argument? • How has the stress on women’s familial roles contributed to or informed certain protests? • Does non-violence enable both sexes to transcend conventional gender roles (as argued by Carol Flinders) or does it play on them to enhance its emotional potency? • Is female non-violence predominantly personally motivated rather than ideologically? • Is it generally shaped by any theoretical understanding of non-violence or does it tend to be spontaneously generated from below? Key References: Eglin, Josephine, Women and peace: from the Suffragists to the Greenham women’ in Taylor and Young (eds.), Campaigns for Peace: British Peace Movements in the Twentieth Century. Flinders, Caroline, Nonviolence: Does Gender Matter?. www.turningthetide.org McAllister, Pam, ‘You Can’t Kill the Spirit: Women and Nonviolent Action’ in Zunes, Kurtz and Asher (eds.), ‘Nonviolent Social Movements: A Geographical Perspective’.