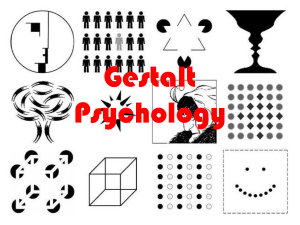

Three Pillars of Gestalt

advertisement

Thomas Fairclough Phenomenology, Field Theory and Dialogue and their application in Gestalt Psychotherapy. 1 Thomas Fairclough Yontef purported that any complete psychotherapy requires at least three elements: a theory of the therapeutic relationship, a theory of consciousness and a scientific theory.1 Gestalt brings together three different components, which are, in themselves robust, theoretical disciplines influencing other areas such as pedagogy, physics, research and other therapeutic theories. This new gestalt has evolved in a way that it is impossible now to see them in isolation; which in effect also reflects the holistic nature of Gestalt. Fractal in that together, their patterns and processes are so repeatingly intertwined, like a rich, fluid tapestry and related at every level, that this format is simply my attempt at a ‘categorised framework’ for the purpose of a theoretical overview. Phenomenology Phenomenology is a 19th century, Husserlian concept, borne from the philosophical movement of existentialism at a time of crisis within the natural sciences. Husserl said that we don’t inhabit a world of science. We inhabit a world of meaning and significance to us, to a more lived experience. A ‘life world’2. From this he developed descriptive phenomenology (eidetic) and subsequently Heidegger developed interpretive phenomenology (hermeneutic). For Husserl, it was essential that: …the researcher to shed all prior personal knowledge grasp the essential lived experiences of those being studied. This means that the researcher must actively strip his or her consciousness of all prior expert knowledge as well as personal biases3 In practice, this is ‘bracketing’ which is the concept of holding back opinions, biases, judgements in honour of the other persons’ subjective experience. This was what Husserl considered to be transcendental subjectivity4. Three Husserlian components of being an effective phenomenologist were: ‘Bracketing’ or The Rule of Epoche. Another rule was The Rule of Description, which is to focus only on description as opposed to interpretation. The Rule of Horizontalization ensures that one doesn’t prioritise certain things above others and that all information has potential. Interestingly Joyce and Sills add to these components by adding Active Curiosity, which I also feel is essential in any Gestalt enquiry. Heidegger believed that ‘bracketing’ wasn’t possible. He believed that we were separate yet part of the world. However he posited that it was this separateness that was the motivating driver in needing contact with ‘other’ in order to assuage the 1 Schulz, F. Roots & Shoots of Gestalt Therapy Field Theory – Historical & Theoretical Developments Mulhall, Phenomenology (Radio 4) 3 Natanson, (1973) Edmund Husserl: Philosophy of Infinite Tasks pg.727 2 4 Ibid 2 Thomas Fairclough emptiness and isolation of conscious existence. Admitting isolation whilst also living with a yearning to belong causes us ‘existential angst’, which we can bypass by living in Sartrean ‘bad faith’5; essentially meaning to live ‘in-authentically’ or ‘choosing not to choose’, by not accepting the ultimate emptiness, freedom and isolation of human existence. Jacobs felt that many of us do this to survive the harsh reality of consciousness. Most people operate in an unstated context of conventional thought that obscures or avoids acknowledging how the world is. This is especially true of one's relations in the world and one's choices. Self-deception is the basis of inauthenticity: living that is not based on the truth of oneself in the world leads to feelings of dread, guilt and anxiety. Gestalt therapy provides a way of being authentic and meaningfully responsible for oneself. By becoming aware, one becomes able to choose and/or organize one's own existence in a meaningful manner.6 Heidegger’s philosophy, although more interpretive in nature was more compatible with Gestalt because it acknowledged that ‘field’ cannot be stripped from one in service of the other and although Husserl set down a process of trying to achieve ‘transcendental subjectivity’, it was ultimately doomed from the outset. Joyce and Sills talk with a Heideggarian slant when they say: In practice, of course, it is impossible to bracket in this way for more than moments at a time and indeed it would be impossible to function without our assumptions and attitudes.7 Husserlian emphasis on the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of a situation is ‘intentionality’; the idea that states of consciousness have a feature of aboutness to them, they are directed towards something8. For instance I am angry about something. I am thinking about something. The relation between the thing I’m thinking of (a chair as something to sit on) and the way in which I’m thinking about it (my experience of the chair being a place where I, as a child was sent when I was naughty and the meaning I make from this). How the world appeared in phenomenology became of more importance than how it may objectively be. Phenomenology according to Merleau- Ponty is: …the study of the appearance of being to consciousness, rather than taking for granted its possibility in advance.9 This existential, holistic stance was a radical conceptual shift from the existing dualistic standpoint. Descartes maintained that we were ‘souls’ carried in a vessel (body) and that they existed as separate entities. Reason was considered ‘higher’, more evolved and more reliable in meaning-making; and our physicality was considered ‘lower’, 5 Sarte, J. Being & Nothingness pg. 162 Jacobs, 1978 in Yontef, Awareness, Dialogue and Process: Essays on Gestalt Therapy 7 Joyce & Sill, Skills in Gestalt Counselling & Psychotherapy pg. 17 8 Mulhall, Phenomenology – (Radio 4) 9 Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception pg. 62 6 3 Thomas Fairclough primitive and less reliable. This compared radically with an emerging existentialism claiming that we can only know the world from our own particular ‘lens’ and any attempt at trying to understand it from an objective point of view was not only futile, but impossible. Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception10 is an attempt at solving the problem of Cartesian dualism and moving towards ‘existential holism’. Our bodies were no longer separate to our minds and rather than being limited to being rational animals, we were considered to be ‘sensing’, embodied organisms with a wealth of information to be had. Sensing, however, invests the quality with a living value, grasps it first in its signification for us, for this weighty mass that is our body, and as a result sensing always includes a reference to the body.”11 In my personal and professional experience, this ‘dualism’ is densely steeped within Western culture and it is commonplace to hear comments like: “My mind knows what’s best for me, but tell my body that”, reflecting the disconnectedness many people feel between mind and body. Related to this is the law of pragnanz12 which essentially means that humans perceive in the simplest way possible; so in Gestalt, by raising awareness a client will gather more comprehensive information and ‘fill in the gaps’ in a way that makes something more meaningful and understandable. The above is clearly only a ‘thumbnail’ sketch of a whole philosophical movement, but regarding its clinical application, it is understandable why this is essential to psychotherapists in understanding our clients’ experience and ‘meaning-making’, if we are to help them. Working phenomenologically can come as a surprise to clients, as is often a complete paradigm shift. Learning a ‘new way’13, to understand the world: “I am my body, my body is me” can be difficult, certainly at first. For instance, working phenomenologically in my own therapy I learned that I often sit on one leg and am unaware of this until it becomes uncomfortable. Instead of deflecting by saying ‘I sit on my leg’, I experiment with other phrases such as ‘I sit on myself’, ‘I restrict myself’, ‘I do things to myself sometimes until I am in pain’. I then glean more information and can make more meaning from how I am in the world in this moment and also understand further how I may modify myself. Our own subjective experience is essential in understanding more wholly how we make meaning in the world. Meaning-making is a complex, holistic process by an 10 idem. ibid. pg.52 12 Pragnanz in Changing Minds 13 I use the term ‘new way’ loosely as it is often seen as something ‘new’ to clients not used to working phenomenologically. 11 4 Thomas Fairclough embodied organism that is part of a greater organism; separate yet paradoxically a part of it; summarised by Merleau-Ponty: To be a body is to be tied to a certain world, and our body is not primarily in space, but is rather of space.14 So if ‘self’ emerges from our phenomenological experience and there can be no ‘self’ without someone or something to relate to, then the world is therefore ‘co-created’. This is a vital element in Gestalt, as it shares responsibility for the relationship between both client and therapist and can avoid over-responsibility, shame and fears of ‘getting it wrong’; it can also redress the inherent power imbalance somewhat whilst also providing a ‘reparative model’ for other relationships. Field Theory Field theory is integral in understanding the ‘figure-ground’ of Gestalt. Perls Hefferline and Goodman didn’t articulate field theory although they alluded to it. It was later Gestalt theoreticians such as Lewin, Latner, Parlett and Yontef that developed its importance within Gestalt. Field theory originated in physics before it was integrated into Gestalt and it is considered its own discipline: Gestalt Theory Field Theory in some quarters. Its scientific determinism was difficult to integrate into Gestalt in a disciplined sense, not in so much that it was ‘I-It’ based, but that it lacked the ‘I-Thou’. This also from a philosophical standpoint raised (not for the first time) the whole issue of ‘free will versus determinism’. Our philosophical view on this is clinically significant for instance working with issues such as addiction or where clients feel that they have no control over their choices. There is clearly not enough space here to give credence to this vast subject but it does raise questions regarding autonomy, agency and responsibility in the truest and fullest of senses and whether we can be truly free in a predetermined world. The term ‘field’ used in this context does not just mean the environment, but also physiological and psychological processes which although do not necessarily ‘exist’ in themselves in matter form, are still living dynamic forces or influences. The physicist Faraday originally coined the term ‘field theory’. Using an experiment with iron filings on a piece of paper with a magnet underneath, he observed the ‘field’ in how the iron filings dispersed on the paper and calibrated according to each other. This ‘field’ wasn’t a material thing in itself but a ‘force-field’, influenced by all the elements within it and vice versa. Not only was this field not an entity in itself it was also not a fixed thing. It is (like ‘self’) a dynamic process. Einstein then went onto confirm that fields were now established as real, even though they were immaterial!15. Field theory could 14 15 Merleau-Ponty, Perception of Phenomenology pg. 184 Schulz, Roots and Shoots of Gestalt Therapy Field Theory: Historical and Theoretical Developments 5 Thomas Fairclough not only make sense of something as massive as the solar system but also of something as small as what was then the atom (now of course DNA). Indeed this facilitated a move away from Newton’s atomistic and reductionistic view of the world. It was also completely in keeping with the theory of relativity and quantum physics so it came with a robust pedigree to be assimilated into the roots of Gestalt. Indeed the word ‘gestalt’ refers to the shape, configuration or whole, the structural entity, that which makes the whole a meaningful unity different from a mere sum of parts16. In true (and once again ‘fractal’) reflection of field theory, it itself changes according to the field conditions, so although field theory in its fullest sense incorporates the whole universe, in its clinical application with clients we attempt to be realistic in our awareness of the whole field and limit it to the clients’ internal/external world, our own internal/external worlds and to the ‘in-between’. Emerging from this is a new gestalt and what happens within this process is where the real therapeutic work begins. What becomes a focus in the ‘therapeutic relationship’ is ‘figural’ and the context in which it occurs, is the ‘ground’, whilst also being part of a larger field: A field is a systematic web of relationships and exists in a context of even larger webs of relationship.17 It was Lewin who applied ‘field theory’ to Gestalt theory as an attempt to understand what the primary motivating driver in human behaviour was? Was it the subconscious? The Id? External influences? Archaeological experiences? Lewin introduced the concept that the need organises the perception of the field and the acting in the field 18; that we behaved in accordance with our perception of the world and that this was an interactive process. Our phenomenological experience affected how we saw and behaved in the world. That in any given situation we do not perceive isolated fragments, but we take in the whole of the situation and we calibrate our meaning accordingly (related to the law of pragnanz). This was radical in the sense that Lewin was proposing that we were not solely responsible and that society had a part to play in how human beings, feel, think and behave. It is from here that we see the holistic approach in Gestalt developing further. Smuts considered that the holistic organism contains its past and much of its future in its present and that as organisms, we are a self-regulating entity19, which became one of the bedrocks of Gestalt theory. Parlett developed five principles in Gestalt Theory Field Theory: 16 Yontef, 1993, Awareness, Dialogue and Process: Essays on Gestalt Therapy p. 181 Yontef, 1993, ibid. pg. 298 18 Schulz, F. Roots and Shoots of Gestalt Therapy Field Theory: Historical and Theoretical Developments 19 Smuts, in Wulf, R. The Historical Roots of Gestalt Therapy Theory 17 6 Thomas Fairclough 1) The principle of changing process – that everything is forever changing. Even though processes will sometimes follow familiar patterns, they are still in a constant state of flux as hypothesised by Heroclitus centuries beforehand when he said that you can not step into the same river twice20. It is important to be mindful of this when clients (and therapists) report ‘stuckness’; although impossible, still accepting that it may feel like this. 2) The principle of singularity – in that each situation is an emergence of something completely new, never seen before and although perhaps similar, it is not exactly the same as the other and therefore has new potentialities within it. This has clinical significance in that most clients come to therapy to change something about themselves 3) The principle of possible relevance – this reminds the psychotherapist that every single element of a given situation is important and latching onto one facet, particularly too quickly can eliminate other possibilities from emerging. 4) The principle of contemporaneity – this is integral within Gestalt in that all events can only be experienced in the here and now. History is experienced now in how we remember an event and the future is experienced now in how we anticipate (which is also influenced by how we view our past and present experiences). Essentially, the past is dead, no longer relevant in any other way than how we perceive it to be now. 5) Perspectival view on reality – within the field we can never experience any event in the same way as another. This brings to mind for me how I was taught in my early training that empathy is the ability to ‘walk in someone’s shoes’. This is an unattainable and therefore unrealistic goal in clinical practice, because one can not wholly understand any event or experience, there will always be other factors, based on the client AND the therapist’s ‘life space’21. It is also vital to remember in practice that it is certain that the client will definitely have a very different experience of therapy than the therapist. DIALOGUE Dialogic method has its roots in existentialism in that the focus is on human existence and their relationships with each other and the world according to their own direct experience. Gestalt owes this method primarily to Buber; an heir to the likes of Kant, Nietzsche and Schopenhauer. His best known work is I and Thou22 where he postulated that we are beings that can enter into dialogue with any aspect of the world, not just other human beings. He didn’t however go as far as Nietzsche in denying the existence of God; indeed for Buber the ultimate I–Thou was with God. However he did agree that humans objectified the world as a means to an end (I–It), rather than as an end in 20 Heroclitus in, Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy Brownell, 2010, in Schulz, F. Roots and Shoots of Gestalt Therapy Field Theory: Historical and Theoretical Developments p. 137 22 Buber, M. I and Thou, trans. by Ronald Gregor Smith 21 7 Thomas Fairclough itself (I-Thou) and that this was a cause for human anguish. His focus was on the ‘in between’ or the ‘encounter’ and this is where the true nature of dialogue exists. In those rare moments when a deep realness in one meets the other it is a memorable ‘I-Thou relationship’ as Martin Buber, the existential Jewish philosopher would call it. Such a deep and personal encounter does not happen often but I am convinced that unless it happens occasionally we are not human.23 Buber wasn’t suggesting that the only aim in life was in the I-Thou or that I-It was inherently ‘bad’; but that they were two ends of a continuum and both part of healthy functioning. For instance, I hope in my work that there are many I-Thou experiences between my clients and I, however our experience moves to I-It functioning when we exchange money. Dialogic method – 1) Presence – In contrast to psychoanalysis where the therapist was a ‘tabula rasa’ to be projected upon, the presence of an authentic self in the meeting not only models, but is in service of the client. Healthy expression from a therapist comes in the form of sharing the impact within the session the meeting may be having on the therapist and disclosure of this kind is at the heart of Buberian dialogue. Disclosure of inappropriate material from the therapist’s life is clearly not. A good caveat is to ask one’s self: “how is this in the service of the client?”. 2) Inclusion – A willingness to be affected by the encounter and to try and look at the world from the client’s perspective whilst acknowledging that this can never be achieved 100%. Meeting someone ‘as they are’ is an accepting process and is what Buber also called ‘confirmation’24. To meet a client with a view to what they are doing right now as ‘wrong’, ‘deficient’ or pathological in some way is not practising inclusion. However if one completely becomes confluent and (tries to) see the world in exactly the same way as the client, inevitably one could be drawn into also assuming that there can be no potential for change (for instance, in the case of a client feeling completely hopeless). The therapist has to keep a sense of self in order to be potent. Also if a therapist can be facilitative in a client becoming accepting of where they are right now, (leaving aside the paradoxical effect this can have in ‘change’) this can also reduce feelings of shame. Buber influenced other ‘dialogical pioneers’ such as Hans Trub who coined the term ‘”healing through meeting” and Maurice Freedman with “healing dialogue”, along with other eminent names such as Rogers, Maslow, May, Binswanger, Yalom and Laing.25 23 Hycner, Between Person and Person pg. 95 Buber, M. I and Thou, trans. by Ronald Gregor Smith 25 Hycner, R. Between Person and Person pg. 90 24 8 Thomas Fairclough Buber, in true existential style acknowledged and felt the existential anguish of human ‘separateness’ and sought comfort in the contact he could achieve with the world in the ‘in-between’. Echoed later by Laing: Each and every man is at the same time separate from his fellows and related to them. Such separateness and relatedness are mutually necessary postulates. Personal relatedness can exist only between beings who are separate but who are not isolates.26 To conclude here is an example of a situation which hopefully encompasses all three pillars of Gestalt: A colleague told me of an experience she had on some training when a piece of painted stone/brick covered in jagged plaster was passed around the room. They were asked about their awareness as they saw, felt, thought and generally experienced the object as they casually passed it around the room. They were all rather ‘non-plussed’ and shared their awareness of it looking craggy, feeling rough, weighing rather heavy, the colours being plain, it looking dirty. The group were then told that the object was a piece of the Berlin wall. Suddenly everything changed, the group mood, their emotions, their perceptions, their thoughts, their behaviour. They started to pass it more carefully and respectfully, their gasps reflected their awe in holding a piece of history. This added piece of information changed their perceptions/descriptions of its weight, its colour, its texture as they shared more vibrant and rich descriptions of the very same object. Their background (historical field) had a particular effect on their here-and-now experience (phenomenology) which had an effect on their relation to others/objects (dialogue), which had an effect on the field and so on ad infinitum. From a phenomenological and field perspective, my very existence depends upon my being in contact with the world and my world being in contact with me. I touch the world and the world touches me in a dialogue that changes both my world and me.27 Gestalt theory’s clinical significance is its revolutionary spirit in that at its very foundations, it acknowledges personal responsibility whilst accepting the inevitability of not existing in a vacuum. 26 27 Laing, R.D. The Divided Self pg. 26 Mann, D. Gestalt Therapy – 100 Key Points & Techniques pg. 145 9 Thomas Fairclough BIBLIOGRAPHY Buber, M. I and Thou, transl. by Ronald Gregor Smith (Edinburgh: T. and T. Clark. 2nd Edition New York: Scribners, 1958. 1st Scribner Classics ed. New York, NY: Scribner, 2000, c1986) Hycner, R. Between Person and Person (Gestalt Journal Press, 1993) Joyce & Sills, Skills in Gestalt Counselling & Psychotherapy (Sage Publications, 2006) Laing, R.D. The Divided Self (Penguin, 1968) Mann, D. Gestalt Therapy – 100 Key Points & Techniques (Routledge, 2010) Merleau-Ponty, M. Phenomenology of Perception (Routledge, 2014) Natanson, M. (1973). Edmund Husserl: Philosophy of Infinite Tasks (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press) Parlett, M. (2005). Contemporary Gestalt Therapy: Field Theory. in A. Woldt and S. Toman (Ed.), Gestalt Therapy, History, Theory and Practice (pp. 41-65). (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. Philipson, P. (2001). Self in Relation (Highland, NY: The Gestalt Journal Press, Inc.) Sartre, Jean-Paul; translated by Hazel E. Barnes [1958] (2003). Being and Nothingness (London: Routledge) p. 649 Yontef, G. (1993) Awareness, Dialogue and Process: Essays on Gestalt Therapy (Highland, NY: The Gestalt Journal Press) JOURNALS Parlett, M. Reflections on Field Theory British Gestalt Journal 1991 1, pgs. 68-91 ONLINE RESOURCES Pragnanz Accessed online: 03/02/15 http://changingminds.org/explanations/perception/gestalt/pragnanz.htm Schulz, F. Relational Gestalt Therapy: Theoretical Foundations and Dialogical Elements Accessed online: 18/12/14 http://www.gestalttherapy.org/_publications/RelationalGestaltTherapy.pdf Schulz, F. Roots and Shoots of Gestalt Therapy Field Theory: Historical and Theoretical Developments, in Gestalt Journal of Australia and New Zealand, 2013, Vol 10 10 Thomas Fairclough (Accessed online: 14/11/14) http://www.gestalttherapy.org/_publications/RootsShootsofFieldTheory.pdf Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/heraclitus/ Wulf, R. The Historical Roots of Gestalt Therapy Theory (Accessed online: 19/01/15) www.gestalt.org/wulf.htm OTHER REFERENCES Mulhall, Phenomenology – Radio 4. 22/02/15 11