ANALYSIS OF VOCABULARY PRACTICES IN A TITLE 1 SCHOOL

A Thesis

Presented to the faculty of the Graduate and Professional Studies in Education

California State University, Sacramento

Submitted in partial satisfaction of

the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF ARTS

in

Education

(Language and Literacy)

by

Tawna Turner

SPRING

2014

© 2014

Tawna Turner

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ii

ANALYSIS OF VOCABULARY PRACTICES IN A TITLE 1 SCHOOL

A Thesis

by

Tawna Turner

Approved by:

__________________________________, Committee Chair

Porfirio Loeza, Ph.D.

__________________________________, Second Reader

Cid Gunston-Parks, Ph.D.

____________________________

Date

iii

Student: Tawna Turner

I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the

University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library

and credit is to be awarded for the thesis.

__________________________, Graduate Coordinator

Albert Lozano, Ph.D.

Graduate and Professional Studies in Education

iv

___________________

Date

Abstract

of

ANALYSIS OF VOCABULARY PRACTICES IN A TITLE 1 SCHOOL

by

Tawna Turner

Statement of Problem

Vocabulary knowledge plays a critical role in reading comprehension and

students’ academic success, but many students start their school careers without

adequate vocabulary knowledge. Schools can play an important role in building

students’ vocabularies, but current primary school instruction is not making a

significant impact on students’ vocabulary growth. The purpose of this study is to

analyze the vocabulary practices in kindergarten through third grade classrooms in a

Title 1 public school to determine the level of systemization and the extent that current

practices align with research.

Sources of Data

Data was gathered through open-ended interviews with a sampling of

kindergarten through third grade teachers. Interviews also included the district coach

assigned to the school and the school principal. Additionally, classroom observations

were conducted following teacher interviews to gain a deeper understanding of

v

specific vocabulary practices. This information was analyzed in conjunction with data

gathered from an extensive review of literature in the field of vocabulary instruction.

Conclusions Reached

Following analysis of the research, the author has concluded that guidance and

direction at the administrative level is critical in establishing effective vocabulary

instruction in the classroom. Vocabulary instruction has not been identified as a high

priority at the school, although teachers and administrators believe vocabulary

knowledge is critical. Without direction from the administrative level, teachers are

doing the best they can. However, they lack training and resources and do not feel they

have enough time in the day. These challenges result in limited vocabulary instruction

that varies between classrooms and is only partially grounded in research.

_______________________, Committee Chair

Porfirio Loeza, Ph.D.

_______________________

Date

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Chapter

1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 1

Primary Research Questions............................................................................. 3

Rationale ........................................................................................................... 3

Methodology..................................................................................................... 6

Definition of Terms .......................................................................................... 7

Limitations and Delimitations of the Research ................................................ 8

Organization of the Thesis................................................................................ 9

2. REVIEW OF LITERATURE ............................................................................... 11

Increasing Vocabulary Knowledge Through Read Alouds ............................ 12

Considerations for Direct and Explicit Instruction ......................................... 17

Incidental Learning of Vocabulary Through Independent Reading ............... 21

Considerations for Word Selection ................................................................ 26

3. METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................... 31

Research Design ............................................................................................. 31

Sample and Size ............................................................................................. 32

Access and Consents ...................................................................................... 33

Data Collection ............................................................................................... 34

Data Analysis.................................................................................................. 35

vii

4. ANALYSIS OF THE DATA ............................................................................... 38

Perceived Importance of Vocabulary Incongruent with Educator

Knowledge ...................................................................................................... 38

Effectiveness of Current Vocabulary Instruction is Unknown by

School Educators ............................................................................................ 43

Challenges to Effective Vocabulary Instruction Stem From Lack of

Administrative Prioritization .......................................................................... 47

Vocabulary Practices Lack Cohesiveness and Systemization ........................ 54

Implications of the Findings Specific to the Research Question .................... 61

5. FINDINGS AND INTERPRETATIONS............................................................. 66

Discussion....................................................................................................... 66

Significance .................................................................................................... 68

Implications .................................................................................................... 70

Methodological Issues and Research Limitations .......................................... 72

Areas for Future Research .............................................................................. 74

Conclusion ...................................................................................................... 76

Appendix A. Interview Questions for Classroom Teachers ..................................... 78

Appendix B. Interview Questions for District Coach and Principal ........................ 80

References .................................................................................................................. 82

viii

1

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

Every year students enter preschool and kindergarten classrooms and begin

their formal education in reading. Teachers provide instruction in a variety of areas

including letter and sound recognition, phonemic awareness, directionality, decoding

and comprehension strategies. Instruction is presented in both whole group and small

group settings with different schools using a variety of curriculums and approaches to

reading instruction. Like many of today’s educators, the majority of this researcher’s

teaching career was spent in urban schools teaching socioeconomically disadvantaged

students—many of whom have limited family support and are learning English as a

second language. Through years of discussing books both in small group and whole

class settings, it has become evident to this researcher that students’ lack of

vocabulary knowledge affects their ability to access and understand text. This

researcher has also noted that low vocabulary knowledge reduces the effectiveness of

reading instruction for beginning readers; even basic letter books or rebus books are

inaccessible to students who do not know the names of the pictures.

Assigned readings and class discussions in graduate courses also highlighted

the importance of vocabulary knowledge and the challenges teachers face in

developing students’ vocabularies. Although children may be in the same class

receiving the same instruction from the same teacher, research has demonstrated a

significant disparity between individual student’s vocabulary knowledge. This might

be expected when English is a second language, but reading ability and socioeconomic

2

status play a large role; sadly, differences in vocabulary knowledge are unlikely to

change once they are established (Beck & McKeown, 2007). Knowing that many so

many students are impacted by these factors and that vocabulary knowledge plays

such a critical role in reading, speaking and writing, this researcher felt there was an

urgent need to learn more about effective instruction and how public schools are

utilizing that knowledge.

As educators work to provide the best reading instruction possible, an

increasing focus on the importance of vocabulary knowledge has caused many

teachers to question if they have the knowledge or resources to provide the necessary

instruction and exposure to vocabulary (Blachowicz, Fisher, Ogle, & Watts-Taffe,

2006). An additional layer of concern is added when teachers are instructing students

with challenges known to impact vocabulary knowledge (low socioeconomic

background, struggling readers, etc.). While there is inherent value in studying

vocabulary instruction, it is not enough. Implementing research-based findings in

actual classrooms is necessary to truly impact teacher instruction and student learning.

This researcher believes there is value in examining current vocabulary practices in K3 classrooms in an operational Title 1 elementary school to determine how vocabulary

instruction is being provided and how purposeful and systematic the implementation

of practices is. Interviews and observations at the school site will provide valuable

insight into the degree and extent that research-based vocabulary practices are

transferred to classrooms.

3

Primary Research Questions

The goal for of this thesis was to answer the following question: How do the

vocabulary practices in a school’s K-3 classrooms align with research on vocabulary

instruction? In order to effectively analyze the practices at the school, the researcher

had to address some secondary questions.

1. How is vocabulary instruction currently being addressed in K-3 classrooms at

the selected school? and

2. What are the research-based components of successful vocabulary instruction?

Rationale

Although the reading process involves many components (decoding, word

recognition, fluency, etc.), ultimately it is about understanding. A research review by

the National Reading Technical Assistance Center (NRTAC, 2010), expanding on the

2000 National Reading Report, stated that students’ ability to understand what they

read has a significant impact on their academic success and plays a critical role in

accessing necessary skills required for 21st century jobs.

Vocabulary knowledge is a significant factor impacting reading

comprehension. Beck and McKeown (2007) stated “A large and rich vocabulary is

strongly related to reading proficiency…. it has long been acknowledged through

correlational and factor‐analytic studies that there is an intimate relation between

vocabulary knowledge and reading competence” (p. 251). A longitudinal study of

students in high poverty schools found that students’ vocabulary skills in the

4

beginning of first grade were significant predictors of later performance in reading

comprehension (Hemphill & Tivnan, 2008).

Research continues, moving beyond correlational data to identify specific

causal links, but it is clear that in order to understand or comprehend text, readers must

understand the words they read. The cumulative number of unknown words a reader

encounters is significant determiner of whether a text is easy or difficult (Stahl, 2003).

This means it is important for readers to have a strong vocabulary base as well as

strategies to help figure out the meaning of new words that come up in reading (Lehr,

Osborn, & Hiebert, 2007). Although a substantial amount of vocabulary can be

learned incidentally from context (Nagy, Herman, & Anderson, 1985), the amount of

reading required is not sufficient for most students. Skilled readers are likely to read

more and their increased volume of words allows them to learn more word meanings.

Less-skilled readers often start with less extensive vocabularies, and because they read

slower, they do not read as many words and gain vocabulary knowledge at a slower

pace. These cycles contribute to increasing the discrepancies in vocabulary

knowledge between students (Stanovich, 1986).

Additional discrepancies in vocabulary knowledge can be linked to students’

socioeconomic backgrounds. This gap in word knowledge starts when children are

toddlers and remains through their school years and even adulthood (Beck, McKeown,

& Kucan, 2013). While there are many factors that contribute to vocabulary

disparities between economically advantaged and disadvantaged learners, Beck and

McKeown (2007) argued that it continues in part because vocabulary instruction has

5

not been a priority in schools. They believe the only way to address the vocabulary

gap evident in students from low- and high-SES backgrounds is to start early and

provide systematic vocabulary instruction.

Because vocabulary is a significant factor in understanding text, schools need a

plan to address vocabulary development and need to train teachers in effective

methods of vocabulary instruction. In their 2001 study, Biemiller & Slonim found

that making an effort to support vocabulary growth in preschool and early primary

years was the simplest means of reducing discrepancies in vocabulary knowledge in

second and third grade. It is not enough for individual teachers to be effective at

vocabulary instruction; schools need a comprehensive, school-wide approach where

an emphasis on vocabulary instruction is consistent throughout all grades (Blachowicz

et al., 2006). This plan is especially critical in the younger grades. According to

Biemiller and Boote (2006), the chances of successfully addressing vocabulary

differences are greatest in preschool and early primary years. Despite the critical need

during this period, the same researchers found current primary school instruction is not

making a significant impact on students’ vocabulary growth.

Given the growing number of students from low-SES backgrounds (up to

23,069,376 students eligible for free and reduced lunch in 2010-2011 school year) and

findings that vocabulary instruction in schools is not meeting student needs, a closer

look into current vocabulary practices is needed (NCES, 2009, 2012). The purpose of

this study is to take an in-depth look at a Title 1 elementary school to determine how

intentional and systematic the vocabulary instruction is for primary grades and the

6

extent that it aligns with research-based effective practices. By gaining a deeper

understanding of how research and practice actually come together in the classroom,

we will be better equipped to address students’ diverse vocabulary needs and can

better prepare them for academic and life success.

Methodology

This study was conducted at an urban Title 1 public elementary school in

Northern California; over 65% of the student population was eligible for free or

reduced lunch and approximately 25% of the student population qualified as English

learners. Data was collected via open-ended interviews and classroom observations.

Teachers interviewed for this study were selected to represent a sample of the school’s

K-3 teaching staff: one teacher from each grade level, representing a range of teaching

experience from 1 to 10 years (10 years was the most experience of any teacher on

staff). All of the K-3 teachers at the site were female, so variation by gender was not

an option. All teachers interviewed were asked a standardized set of questions.

The school principal was also interviewed to provide an administrative

perspective and insight into the school-wide vision for vocabulary practices.

Additionally, the district coach assigned to the school site was interviewed to provide

information on district-related philosophies, goals and requirements related to

vocabulary instruction. The district coach and principal received a modified series of

questions appropriate to their role at the school. All interviews were recorded and

partially transcribed.

7

Classroom observations were conducted to gain a deeper understanding of

vocabulary practices discussed in teacher interviews. The time and length of the

observations varied depending on what was needed to provide the best understanding

of a specific practice. Observation data was captured through anecdotal notes;

additional contact with teachers took place only if clarification was needed following

an observation. Interview transcripts and observation data was analyzed to provide an

overview of the vocabulary practices, perspectives, and challenges within K-3

classrooms.

Definition of Terms

For the purposes of this research, the following definitions will be used:

Familiar reading circumstances—text usually encountered in or outside the

classroom in a natural reading setting

Incidental word learning—learning new word meanings through the

conscious or unconscious use of context clues while independently reading or listening

under familiar circumstances

Instructional context—text that is intentionally written to support readers in

figuring out a word’s likely meaning.

Natural context—authentic text a reader encounters naturally that supports

learning new words

Read alouds—an activity where a teacher reads a text aloud to a group of

students usually, in the form of a book

8

Vocabulary instruction—teaching words with the intent to increase student

knowledge of word meanings

Vocabulary knowledge—the meaning of a word as well as how the word fits

in different contexts

Vocabulary practices—the strategies and methods used to provide vocabulary

instruction

Word lists—specific lists of words selected for vocabulary instruction.

Title I school—a school where a minimum of 40% of the students in the

school, or residing in the attendance area served by the school, are from low-income

families.

Limitations and Delimitations of the Research

This study may be limited by the accuracy of the interviews regarding

perspectives and the extent and type of vocabulary instruction currently provided.

Teachers and administrators may have responded based on how they thought they

should answer rather than how they really felt or what they really did in their

classrooms. To address this concern, the purpose of the research was clearly presented

to each individual when they were asked to participate. Also, participants were

guaranteed that no names would be affiliated with any of the information presented in

the findings. This study represents data from one school, so generalizations are

limited by the small sample size.

One delimitation of this study is that it only represents data from one public

elementary school within a school district. The curriculum flexibility within the

9

district as well as mandated instructional guidelines may prevent the results from

being generalized to a larger student population in other schools. Also, the study took

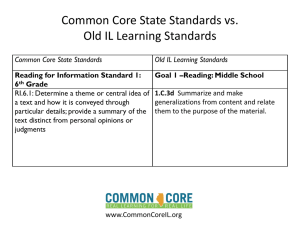

place just prior to the mandated change to California Common Core Standards

effective for the 2014-2015 school year. The implications and effects of implementing

these new standards is unknown and changing conditions within schools may affect

recommendations for future vocabulary practices. Lastly, despite the best efforts of

the researcher, qualitative research involves an element of interpretation and there is a

possibility of misinterpreting data.

Organization of the Thesis

Chapter 1 provided a rationale for the study, an overview of relevant research,

the research questions, and the methodology. The thesis was developed to examine

vocabulary practices in K-3 classrooms in an operating public school and to determine

how research on effective vocabulary instruction is being implemented within those

classrooms. Chapter 1 also identified and defined terms used specifically in the paper

and discussed potential limitations and delimitations of the research.

Chapter 2, the review of current and relevant literature, outlines specific areas

of focus by examining the research of leading experts in the field of reading and

vocabulary instruction. This research provides the basis for the analysis of the

school’s vocabulary practices. Chapter 3 contains a detailed methodology for the

selection of interview subjects, access and permission, how the research was

conducted, and how the data was analyzed. Chapter 4 discusses the research findings

in depth and Chapter 5 discusses the significance of the findings, the implications to

10

the field of education, and recommendations for further research. Chapter 5 also

reviews methodological issues and research limitations.

11

Chapter 2

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

In order to examine how vocabulary research is impacting classroom

instruction, it is first necessary to review the research. The purpose of this literature

review is to examine research that has been conducted in the area of vocabulary

instruction—specifically focusing on grades K-3. Vocabulary instruction is a

comprehensive field; this review focuses specifically on increasing vocabulary

knowledge through read alouds, considerations for direct and explicit instruction,

incidental learning of vocabulary through independent reading, and considerations for

word selection. Information on these topics came from a variety of sources including

peer-reviewed studies, articles, books, and research handbooks. Primary sources were

used whenever possible; however, secondary sources were used if the original was not

available.

A literature review of vocabulary research by the National Reading Technical

Assistance Center found that, “although there is strong evidence supporting explicit

instruction of vocabulary, a question remains regarding which aspect or model of

instruction is best” (NRTAC, 2010). Although different researchers and experts focus

on specific methods of vocabulary instruction, many agree that one way is not

sufficient and that students need the opportunity to interact with words on a variety of

levels (Silverman, 2007). This review examines several ways to do this and offers

guidance on how educators can provide meaningful vocabulary interactions.

12

Increasing Vocabulary Knowledge Through Read Alouds

Instructional practices and activities vary significantly across grade levels,

school districts, and states. However, the practice of teachers reading to students is

common in many elementary classrooms. This activity, often referred to as a read

aloud is especially popular in primary grades and serves many purposes such as

helping students develop an understanding of story features and text organization,

encouraging a love of reading, allowing teachers to model concepts of print, and

introducing students to a variety of sentence structures. Another benefit of read alouds

is that students are exposed to new or unfamiliar vocabulary words. In fact, according

to Stahl & Stahl (2004), books are the place to find words, and “storybook reading is

the most powerful source of new vocabulary, including those academic words that are

valued in school discourse” (p. 67).

One of the reasons children’s books are recognized as a valuable resource for

vocabulary instruction is the complexity of the language compared to other sources

children are exposed to. Hayes & Ahrens (as cited in Graves, 2009) studied

vocabulary exposure from a variety of sources and examined the number of rare words

found in printed texts, television texts and adult speech. They found that children’s

books ranked higher than children or adult television shows and even above typical

conversation between two adults with college educations. Their findings certainly do

not negate the importance of parents and teachers speaking to children, but they do

establish that reading children’s books aloud is a critical means of introducing children

to new vocabulary.

13

Read alouds provide students with access to text they may not be able to

decode independently and provide an opportunity for teachers to discuss new or

unfamiliar vocabulary in context. Biemiller and Boote (2006) refer to most children in

the primary grades as preliterate, a period when students understand oral language

better than they understand language in print. Most K-2 students are only able to

independently read books with simple text, so they are more likely to encounter new

words in books that are read to them— relying on others for exposure to rich

vocabulary. Although students may not be able to read the words themselves, learning

word meanings through read alouds provides a foundation for when they encounter the

words later in independent reading.

Although some words may be learned from context alone (without any verbal

explanation), providing a direct explanation for selected vocabulary words increases

the likelihood that students will learn word meanings. When teachers stop to give

direct explanations of word meanings, they not only provide specific knowledge of the

word meanings, they also draw attention to new words. When young children are

listening to an oral reading of a story they have a hard time sufficiently isolating a

specific unknown word to ask what it means or to actively attempt to figure out the

meaning on their own (Biemiller & Boote, 2006).

In some cases, children can figure out meanings of unknown words from just

listening to books, but often it takes more than merely reading a book to a group of

students to maximize vocabulary learning. Specific techniques during this time make a

significant impact on student learning and retention of vocabulary words. Factors to be

14

considered in using read alouds as tools for vocabulary learning are as follows:

providing word explanations, the value of repeated readings, post-reading review of

selected words, and additional interaction with words.

In a review of previous studies on the effectiveness of read alouds in teaching

new word meanings, Biemiller and Boote (2006) found that a single reading when the

teacher provided word meaning explanations was more effective than repeated

readings with no word meaning explanations (9% vs 15% average gain). Repeated

readings with word meaning explanations were the most effective with around a 26%

gain in vocabulary knowledge.

Sometimes teachers identify vocabulary words from a selected book and

introduce the words before reading the story so the students will be more aware of the

new vocabulary words when they hear them in context. However, Beck et al. (2013)

recommended that with young children (referring to kindergarten through early second

grade) vocabulary words should not be introduced ahead of time and any vocabulary

activities should take place after the book is read. Their reasoning was that students

have a better chance of initially learning new vocabulary words when they hear them

in the rich context of a story.

Whether word meanings should be taught during the reading or after the

reading is up for debate since studies have shown vocabulary growth with both

methods. Beck and McKeown’s 2007 study provided vocabulary instruction after the

book was read and found that students who received instruction on word meanings

showed significantly more word learning than students who received no instruction.

15

Their rationale for teaching words after the read aloud was twofold. First, they felt

students were able to build initial understanding from hearing the words in context.

Second, they felt that providing vocabulary instruction after reading allowed for

deeper discussions without interfering with the meaning of the story. According to

these authors, when read alouds are used specifically for vocabulary instruction,

student comprehension of the book is secondary to the goal of increasing general

vocabulary knowledge. With that mindset, a brief explanation of a word was only

provided during the reading if it was deemed necessary for general understanding

(Beck & McKeown, 2007).

Biemiller and Boote (2006) agreed that teachers should consider students’

listening experiences when deciding how to provide vocabulary instruction through

read alouds. Prior to conducting their official studies, these authors did a pretest and

found that many students did not like it when the teacher repeatedly interrupted the

story to define words. The researchers concluded that this approach might have a

negative effect on the learning experience. To address this concern, they had the

teachers in their studies read the book straight through on the initial reading.

Biemiller and Boote (2006) conducted two studies using narrative read alouds

in K-2 classrooms. Both studies used pre and post-tests to establish vocabulary

growth and the second study used a delayed post-test to measure word knowledge

retention. Their research supported previous findings that students make more

vocabulary gains when word meanings are taught during read alouds than by just

hearing repeated readings of the same books. Their findings indicated that repeated

16

readings (four vs two) are beneficial in increasing vocabulary knowledge for

kindergarten and first grade students, but not for second graders. They also found it

was more effective for teachers to provide all the definitions (rather than asking for

and confirming student definitions) (Biemiller & Boote, 2006).

Beck et al. (2013) also cautioned against asking students to provide the initial

definitions of target words. They argued that the teacher has chosen the word with the

assumption that most students do not know it, and listening to multiple incorrect

guesses wastes valuable time and has the potential to inadvertently reinforce the

wrong meaning. Beck et al. (2013) provided additional guidance on the type of

definition. They recommended student-friendly definitions (not from a dictionary),

giving the following criteria for a definition “(1) Capture the essence of the word and

how it is typically used and (2) explain the meaning in everyday language” (p. 45).

Biemiller and Boote’s (2006) study found that reviewing the selected

vocabulary words led to significant gains, indicating that after introducing new words

during the story, teachers should go back and read the sentences containing the words

and repeat their explanations. On the final day teachers should review all the targeted

words in the book using in different context sentences and provide students with the

opportunity to provide definitions and get clarification as needed. This approach was

effective for short-term vocabulary gains and students seem to retain this knowledge

or even increase their knowledge weeks later.

Biemiller and Boote (2006) suggested that if teachers used these practices, they

could increase student vocabulary knowledge by 400 words a year. One challenge

17

with these recommendations, however, is the time. While vocabulary knowledge is

important, classroom teachers have a wide range of standards to teach in addition to

district-mandated guidelines, assessments, etc. that may limit time dedicated to read

alouds. The read aloud activities recommended for maximum effectiveness would

require teaching approximately 25 word meanings a week over the course of five days.

Each read-aloud block would entail at least a half-hour, be dedicated to a single book

and focus specifically on vocabulary instruction. Many teachers may not feel they

have the time to commit to this each day.

Considerations for Direct and Explicit Instruction

To some extent, vocabulary instruction within the context of read alouds is a

form of direct instruction, as students are explicitly provided with a definition of each

target word. However, there is evidence that students can achieve increased

vocabulary growth and possibly a deeper understanding of word meanings when they

have additional opportunities (other than hearing word explanations during read-aloud

time) to interact with words (Coyne, McCoach, Loftus, Zipoli, & Kapp, 2009;

Silverman & Crandell, 2010). For this reason, additional methods of instruction are

included in this review. Each of the methods in the Silverman study (2007) was

implemented in conjunction with a read aloud where the teacher provided explanations

of the target words during the reading.

Acting Out and Illustrating Words

A study by Silverman and Crandell (2010) found that students with low

vocabulary knowledge could benefit from using different sensory activities to interact

18

with target words. These researchers found a positive correlation when teachers

provided a visual representation of the word and had the students participate in a

kinesthetic movement associated with the word. Silverman and Crandell’s hypothesis

was that having verbal and nonverbal interactions increased student engagement. This

approach was more powerful when new words were discussed in the context of the

story; kinesthetic interactions later in the day or week did not seem to have a positive

impact. The time and planning necessary to do this during a whole class read aloud,

however, may not be worth it, because the benefits of acting out and illustrating

words was not as significant for students with more developed vocabulary knowledge

(Silverman & Crandell, 2010). If the majority of a class does not have low vocabulary

knowledge, schools should consider this approach for targeted small group vocabulary

instruction.

Using Categorization and Word Association

Another approach to helping students develop a better understanding of

vocabulary is to provide opportunities for students to categorize conceptual

vocabulary. This approach is recommended even in the very young grades (Stahl &

Stahl, 2012). These researchers suggested four parts to a semantic mapping lesson but

cautioned that semantic mapping should be taught in conjunction with a book or

specific content standard so students have something to connect to. Because the goal

is for students to make connections between different words and understand how they

relate to each other, this strategy would be most beneficial for richer vocabulary words

19

with multiple associations (i.e. ‘community’ might work well for this strategy whereas

‘locate’ might not).

Stahl & Stahl’s (2012) four parts include the following: Brainstorming (With

teacher guidance, students brainstorm words they know related to the selected topic.);

Mapping (The teacher works with the class to identify three or four categories that

might encompass the generated word list. The categories and associated words are

mapped on the board.); Reading (Students read or listen to a book on the topic.);

Completing the map (The class revisits the map to make changes or additions based on

the reading).

Beck et al. (2013) also recommended providing students with the opportunity

to make connections or associations between target vocabulary words and words they

already know. In Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction they suggest

that after providing a class with student-friendly definitions of the target words,

teachers should ask a series of questions using this basic format: “Which word goes

with…..” and ask the students to select one of the new words. The guideline for

teachers selecting words for association is that there is a relationship between the two

terms—synonyms will not work because the words are too similar. It is also important

for teachers to ask students to provide the reasoning behind their choice—explaining

their thinking and why they made the association makes for richer learning (Beck et

al., 2013).

20

Applying Words in New Contexts

Although introducing new vocabulary within the context of a book is a

recommended method for vocabulary instruction, students may also benefit from

interacting with the words in new contexts as well. The new contexts could be

provided by the teacher as was the case in the study by Silverman and Crandell

(2010). Their research found that student vocabulary growth was greater when

teachers spent more time using the words in contexts outside of the story. Although

additional time seemed to have positive results, teachers should consider the

vocabulary knowledge of their students when considering this approach. The same

study found that students with higher initial vocabulary knowledge benefited more

from this strategy than students with lower vocabulary knowledge. It is possible that

providing many different contexts for a new word might be confusing for those

students (2010).

Another way for students to interact with target words in new contexts

involves students playing a more participatory role. Stahl (2005) suggested several

ways to do this in a classroom setting. One way was to have the students become the

teachers and create their own sentences using the words in different contexts.

According to Stahl this is only effective if the words are used in meaningful context,

not as filler words (2005). For example, the sentence ‘My mom was indignant,’ does

not give any indication of what indignant might mean. ‘When my mom found out dad

forgot her birthday, she was very indignant’ is much more informative. In order to

ensure students create meaningful sentences, Stahl suggested having the class vote on

21

how well the sentence conveyed the meaning of the word. A related activity would be

having students work in groups to create stories using several of the vocabulary words

(Stahl, 2005).

Phonological Representations

While most of the methods suggested for vocabulary instruction involve

students hearing and speaking new vocabulary words, emergent and beginning readers

may benefit from seeing new vocabulary words in writing and focusing on the

phonological elements. Biemiller and Boote’s 2006 study of K-2 students found that

first graders made the largest gains in the study and the only instructional difference

was that the first grade students read the new vocabulary daily from a chart. While

this is not conclusive evidence, the researchers did recommend that reading

vocabulary words might be helpful for some students. The results of Silverman’s

2007 research also supported introducing a phonological element to vocabulary

instruction. In this study, the researcher found that anchoring the instruction to

letter/sound relationships and spelling features was effective for kindergarten or

beginning readers.

Incidental Learning of Vocabulary Through Independent Reading

As previously discussed, targeted vocabulary instruction is increasingly

recognized (and recommended) as a viable method of building students’ language.

However, it is not the only way children learn new words. Due to the vast number of

words students will need to know in order to be successful in school, educators have

22

also directed their focus to another method of vocabulary acquisition: incidental

learning from independent reading.

Obtaining viable research on incidental word learning can be difficult due to

challenges with methodology. If the goal is to ascertain what students could learn in a

natural setting, the act of pretesting targeted vocabulary words may alter the

experience (alerting students to the words they will be assessed on). Additionally, if

studies use unnaturally informative text selected specifically for context, the results

will not accurately reflect the type of text students would typically encounter in their

natural reading environment.

A study of eighth grade students by Nagy et al. (1985) attempted to mitigate

these challenges and provided insight into how much vocabulary growth could

actually be attributed to incidental learning through independent reading. The results

of their study show students can use context in natural text to learn new words—

sometimes after only one exposure to a new or unfamiliar word. However, the

vocabulary growth is small, and significant benefits occur only when (a) students read

substantial amounts of text, and (b) the text they read contains an appropriate ratio of

known to unknown words.

The necessity of substantial reading is due to the low probability of learning

unknown words from context. On average, students will learn the meanings of

approximately 15 of every 100 unknown words they encounter in natural reading

(Swanborn & de Glopper, 1999). This estimated ratio came from a meta-analysis of

20 incidental word learning experiments performed by these researchers. It is difficult

23

to extrapolate how many new words meanings could result because word knowledge

differs drastically for every individual. However, it is clear that when students read

more they increase their odds of encountering unknown words and consequently, the

likelihood of learning the meanings of those words.

Swanborn and de Glopper (1999) found when students encounter too many

unknown words it lowers the chance they will be able to learn meaning from context.

Specifically the researchers found that, “if the density of unknown words in a text is

low, for example 1 word on every 150 words, the probability of learning a word will

be about .30, 1 unknown word on every 75 will yield .14, 1 unknown word on every

ten words gives .07” (p. 275). Again, because vocabulary knowledge varies

significantly from each student, it is difficult for teachers to provide students with

books containing optimal ratios of known to unknown words. These findings indicate

that students with lower vocabularies will not see substantial benefits in vocabulary

growth from reading books significantly above their reading level.

The power of incidental learning from context is that it provides an alternative

means of increasing student vocabulary growth outside of direct instruction, which

requires class time, resources and teacher preparation. Vocabulary growth from

independent reading has the potential to occur at any time and in any place where

students are reading. Given the vast number of words students must learn and the

limited amount of time available for vocabulary instruction in the average school day,

this benefit could be significant. In comparing incidental learning to direct instruction,

24

Nagy et al. (1985) acknowledged that direct instruction is more efficient, but that “the

strength of learning from context lies in its long-term, cumulative effects” (p. 252).

The two requirements (substantial reading and an appropriate ratio of known to

unknown words) might be met easily by average or above average readers who enjoy

reading and have wide access to appropriate text. For struggling readers, however, it

is more of a challenge. Struggling readers typically read less, are more likely to read

books with simple, familiar words and are focused primarily on decoding text. These

factors limit the effectiveness of wide reading approach for those students. Wide

reading is also difficult for students whose access to books is limited by

socioeconomic or situational challenges (limited books available in the home, no

access to a library, etc.).

In the second edition of Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary

Instruction, Beck et al. (2013) specifically cautioned against teachers relying on wide

reading for vocabulary instruction. They argued that because of the disadvantage to

struggling readers, this approach has the potential to broaden the gap between

individual student’s vocabulary knowledge. According to Beck et al., struggling

readers have a harder time knowing when they do not understand what a word means

and are also not as skilled at using context to accurately determine meanings for

unfamiliar words. For these reasons, teachers who rely heavily on wide reading for

student vocabulary gains may not be addressing the vocabulary deficits of students

with the greatest need (2013).

25

Knowing that students have the potential to increase their vocabulary

knowledge through independent reading, educators should encourage students to read

extensively (Pressley, 2001). Additionally, Swanborn and de Glopper’s meta-analysis

(1999) showed evidence that students can improve their incidental word learning

skills. Their analysis indicated that fourth grade students could begin to derive and

retain word meanings from context and that 11th graders were four times as likely as

4th graders to learn a word from context. If students can get better at learning from

context, they would likely benefit from instruction in this area. In fact, Nagy and

Anderson argued that any approach to vocabulary instruction should provide some

ways to lessons to improve children’s ability to learn new words on their own (1984).

Instruction in morphemic analysis (the study of affixes and roots) is one way teachers

can help students increase their independent word-learning skills. Although this is a

rich and comprehensive area of research, most of the studies surrounding this area of

instruction have been conducted in the middle grades (Mountain, 2005). Because the

focus for this paper is K-3, morphemic analysis is not included in this review of

literature, although Mountain suggested the methods used for older students could be

effectively adapted to primary grades. Additional support for teaching young students

word learning strategies comes from The California Department of Education

Common Core standards, which included word analysis as a language standard

starting in kindergarten: K.L.4: “Determine or clarify the meaning of unknown and

multiple-meaning words and phrases based on kindergarten reading and content”

(California Department of Education, 2013). The standard is explained in more detail

26

in K.L.4b: “Use the most frequently occurring inflections and affixes (e.g., -ed, -s, re-,

un-, pre-, -ful, -less) as a clue to the meaning of an unknown word.” Further

exploration and study of morphemic analysis in primary grades is recommended as

more research becomes available.

Considerations for Word Selection

If educators choose direct instruction as a means of increasing student

vocabulary, they must decide which approach will be most beneficial; a similar

decision must occur when selecting which words to teach. A study by Nagy and

Anderson (1984) estimated that printed English text in schools contained

approximately 88,533 word families. This large number of words students are likely

to encounter is daunting given that students only learn an average of 2,500 root word

meanings during the primary grades (Biemiller & Boote, 2006). Due to limited hours

in a school day (with numerous district and state mandated standards to cover within

that time) and wide variability in individual student’s vocabulary, it is crucial for

educators to be purposeful in their selection of words for instruction.

The basic tenets of word selection are fairly straightforward: identify and teach

words that students do not know and will need to know in order to understand reading

material encountered during the school year. Identifying what those words are,

however, is more challenging and researchers differ on the best approach—with two

general philosophies emerging. One philosophy favors individual teachers looking at

upcoming reading material and using their best judgment combined with a set of

general guidelines to select the most appropriate words for instruction (Beck et al.,

27

2013). The other approach is to choose from a list of words that have been compiled

by different methods sources such as frequency of word occurrence (Graves, 2009) or

the general developmental sequence of word learning (Biemiller, 2005).

Beck et al. (2013) advocated for teachers using their best judgment and

knowledge of student needs to select the vocabulary words they will use for

instruction. Specifically, the authors recommend selecting Tier Two words from text

the students will be reading as part of the class. This tiered word system is a general

approach for organizing words into three categories. According to Beck et al., Tier

One words are words that are commonly found in oral language and thus not a priority

for instruction. Tier Two includes words that are found primarily in written language

and likely to be found across many disciplines. Tier Three includes words that are

associated primarily with a specific field of study (i.e. Cretaceous) or that are

extremely rare.

Beck et al. (2013) set out additional criteria to help teachers correctly select

Tier Two words for instruction. Teachers should consider words in terms of how they

relate to students’ existing conceptual understandings—selecting words that relate to

concepts students already have a general understanding of, but that involve a more

specific or precise application. When students can relate new vocabulary to existing

knowledge they are better able to build connections between words. Instructional

potential was another criteria guiding Tier Two selection; teachers should select words

that have nuanced meanings which vary depending on the context they are used in.

By choosing words with several shades of meaning, teachers provide students with the

28

opportunity to interact with the words in a variety of contexts and to apply that

knowledge in reading. Two other considerations for teachers: (a) don’t chose a word

if you can’t explain what it means in words the students understand, and (b) use your

knowledge of your students to choose words that they will find interesting and be able

to relate to their lives (Beck et al., 2013).

Words lists are another possibility for teachers to use in selecting vocabulary

words for instruction. Graves (2009) suggested a list titled The First 4,000 Words,

which he compiled in conjunction with two colleagues. Essentially the list is the 4,000

most frequent word families listed in the order of frequency. Graves and his

colleagues have used that list as the basis of a web-based vocabulary program

available for purchase, but if educators are interested in using the list as resource for

vocabulary instruction, it is available to the public via the product website. The list is

available in two formats; the first is simply the list of the 4,000 most frequent word

families (referred to as the 4KW Source List). The second format is the same list, but

sequenced by frequency within the following categories: target words, function words,

proper nouns and the 100 most frequent words

(http://www.sewardreadingresources.com/fourkw.html).

Biemiller (2012) suggested another option for teachers who want to use a word

list to guide vocabulary instruction. He has compiled a list of “words worth teaching:”

1,600 high priority words for grades K-2 and 2,900 high priority words for grades 3-6.

His method of selecting words was based not on frequency like Graves, but on the

belief that children learn word meanings in a general sequence and would benefit from

29

being taught words based on that sequence. Three thousand root word meanings were

tested on a sample group of students at the end of second grade; words were

considered high priority if they were known by 40%-79% of students. Biemiller also

used a rating system for another 3,000 word meanings and the results of both methods

were combined to arrive at the 1,600 words. A similar approach was used for the

upper elementary list. The actual lists can be found in his book, the Words Worth

Teaching (2009).

There are benefits and challenges with either approach to words selection.

Teachers selecting Tier Two words from class reading selections utilizes the teacher’s

knowledge of their students interests, existing conceptual understandings and allows

words to be introduced in natural context. However, when words are chosen in this

fashion some key words might be missed either because they were not in the texts or

the teacher didn’t identify them as important. Also, it would be difficult to know

which words students in a particular grade level have been introduced to, since the

words were selected by individual teachers with different student needs and varying

levels of expertise in correctly identifying Tier Two Words.

Using words lists to guide instruction is more systematic and makes it easier to

track which words students have been taught. However, because vocabulary

knowledge varies significantly between individuals, a generic word list may not

provide the most relevant words for a specific group of students or for the words they

will encounter in class reading material. Another caution with this approach is in the

strength of the word list. Graves list of 4,000 words is based on frequency, but Nagy

30

and Anderson (1984) cautions against depending to heavily on frequency studies

because they are generated from large samples of text, but may not accurately reflect

targeted reading in specific content areas.

31

Chapter 3

METHODOLOGY

The purpose of this study is to identify and analyze educator perspectives and

practices related to vocabulary at a Title 1 elementary school to determine how

intentional and systematic the vocabulary instruction is. Specifically this study

focuses on grades K-3 and examines the extent that the school’s vocabulary practices

align with research findings on effective vocabulary practices. In an effort to address

the primary research question, a detailed review of literature related to effective

vocabulary instruction was conducted and presented in Chapter 2. The purpose of

Chapter 3 is to provide detailed information regarding the methodology used for this

study. By gaining a deeper understanding of how research and practice come together

in the classroom, schools, credential programs and other related stakeholders in

education will be better equipped to better prepare students for success in school as

well as life.

Research Design

This research study was qualitative in nature. Data was collected via openended interviews from selected staff members and from observations conducted in

selected classrooms. The data was collected in an effort to gain insight into the

current vocabulary practices in K-3 classrooms at the school site as well as the

educator’s perspectives, attitudes and perceived challenges regarding vocabulary

instruction.

32

Sample and Size

This study was conducted at an urban Title 1 public elementary school in

Northern California. The school serves approximately 416 students with 56% of the

student population eligible for free or reduced lunch and 25% of the student

population qualifying as English learners (School Principal, personal communication,

March 26, 2014). This study was specifically focused on vocabulary practices on

grades K-3 so teachers interviewed for this study were selected to represent a sample

of the school’s K-3 teaching staff. One teacher was chosen from each grade level (K3). At the time the data was collected, the site had three kindergarten classes, three

first grade classes, three second grade classes and four third grade classes. The

teachers selected for interviews and observations represented a range of teaching

experience from 1 to 10 years (10 years was the most experience of any teacher on

staff). The kindergarten teacher was in her 10th year, the first grade teacher was in her

4th year, the second grade teacher was in her 6th year and the third grade teacher was in

her 1st year. All of the K-3 teachers at the site were female, so variation by gender

was not an option. In addition to interviews, classroom observations were also

conducted in one class at each grade level K-3. Observations were conducted on

specific vocabulary practices mentioned in teacher interviews and were only

conducted in the classrooms those teachers.

The sample also included an interview with the school principal to provide an

administrative perspective and insight into the school-wide vision for vocabulary

practices. Additionally, the district coach assigned to the school site was interviewed

33

to provide information on district-related philosophies, goals and supports related to

vocabulary instruction. He also provided insight into K-3 vocabulary practices at the

site through his capacity an induction coach for several teachers on the 2-3 team and

his interaction with teachers as the site coach. His specific focus was math, but he was

the only district coach assigned to the school site and the primary means of district

support. The district coach and principal received a modified series of questions

appropriate to their role at the school. The sampling procedure for this study resulted

in an interview sample that included four classroom teachers and two educators with

an administrative role at the school; four observations were also conducted of each of

the four teachers interviewed.

Access and Consents

Permission to conduct the study was initially obtained from the school

principal. She gave her consent but requested a brief written description of the study,

which was submitted to the superintendent over the school. The superintendent

granted permission for both the interviews and classroom observations. After

obtaining permission from school administration, the researcher contacted the

educators selected for interviewing via email and asked if they would be willing to

participate in a study on K-3 vocabulary practices at the school site. The email gave a

brief overview of the purpose of the interview, the estimated length of time required

(30 minutes) and how the data would be used. Once the educators agreed to

participate, they were asked to provide some dates and times they were available. All

34

interviews were conducted at the school site in a space where only the researcher and

interviewee were present.

Research subjects received the interview questions via email and were given

the option of reviewing them prior to the interview. Each educator received and

signed an informed consent form before the interview began. The consent form

explained the purpose of the study, a brief description of what participation would

entail and the measures of confidentiality. Teacher consent forms detailed that they

would allow the researcher to perform 1-2 classroom observations of specific

vocabulary practices. Prior to the interview, participants were asked if they objected

to the interview being audio recorded; all participants agreed to be recorded.

Interviews and observations were conducted by this researcher. Interviews were

conducted after school and lasted between 25 and 35 minutes.

Data Collection

Data was collected via open-ended, one-on-one interviews and observations of

classroom vocabulary practices. Prior to each interview, participants were informed

that the researcher was only interested their existing knowledge and experience; there

were no ‘right answers.’ All teachers interviewed were asked a standardized set of

questions. The questions used during the interview were generated after reviewing

research and literature related to vocabulary instruction. The last question in each

interview was formulated to give participants the option of sharing anything not

covered in the previous questions. Follow up questions were asked to gain

clarification on participant responses or gain further information. All interviews were

35

digitally recorded with an audio recorder and partially transcribed. Additionally the

researcher printed out the interview questions and took notes during the interview.

Interview questions are provided in Appendix A and Appendix B.

Once all the interviews were completed, classroom observations of specific

vocabulary practices were scheduled with each teacher. These observations were

conducted to gain a deeper understanding of vocabulary practices discussed in teacher

interviews. In an attempt to gather accurate data, teachers were verbally informed the

purpose of observations was to gain additional insight into the vocabulary practices in

their classrooms—the researcher was interested in what a vocabulary practice

typically looked like. The time and length of the each observation varied from 10-30

minutes depending on what was needed to provide the best understanding of a specific

practice. Observation data was captured through anecdotal notes; additional contact

with teachers took place only if clarification was needed following an observation.

One observation was conducted in each classroom with a total of four observations.

Three different vocabulary practices were observed. Interviews and observations were

conducted within a 10-week period.

Data Analysis

Interview recordings and notes from interviews and observations were

examined to provide a comprehensive look at the vocabulary practices, educator

perspectives, and challenges within K-3 classrooms at the school site. Specifically

research findings were analyzed to answer the secondary research question: How is

vocabulary instruction currently being addressed in K-3 classrooms at the school site?

36

Interview and observation notes were reviewed to identify the type and frequency of

vocabulary practices in K-3 classes at the school as well as educator attitudes and level

of knowledge and familiarity with effective practices.

Because information regarding vocabulary practices was critical to answering

primary and secondary research questions, interview notes for specific vocabulary

practices were coded. Four vocabulary practices were selected based information

gathered through the review of literature and recurring references in multiple

interviews. Four specific practices were identified: vocabulary instruction through

read alouds, teaching strategies to help students figure out word meanings

independently, explicit vocabulary instruction, and vocabulary instruction through

guided reading. Each of these topics was assigned a different color and the researcher

went through interview notes and highlighted any reference to topic in the

corresponding color. Coded sections of teacher responses were then analyzed in

relation to the review of literature and results were discussed in Chapter 4 of this

paper. Although teachers were asked specifically about many of these practices in the

interview, relevant information also came up as the result of other questions and was

included in coding.

This researcher reviewed the notes and recordings to qualitatively identify

common themes among all participants as well as within teacher and administrator

subgroups. The main areas identified in the review of literature were specifically

focused on in analysis and were used to answer the primary research question: How do

the school’s current vocabulary practices align with research on vocabulary

37

instruction? Information was gathered from a variety of sources: teachers (from

multiple grade levels and with varying years of experience), the school administrator,

district coach and classroom observations. The variety of data sources allowed for

triangulation and provided an overview of K-3 vocabulary practices at the school.

38

Chapter 4

ANALYSIS OF THE DATA

Chapter 3 provided the methodology used to conduct the study. Chapter 4 will

report the results of the research comprising both educator interviews and teacher

observations. Interviews with school personnel provided valuable information

regarding educator attitudes and knowledge related to vocabulary and vocabulary

instruction. Interviews also supplied information on how the school and district were

structured with regard to goals, support, and classroom expectations. It became

increasingly apparent from these conversations and subsequent observations that

vocabulary instruction in schools is a complex topic. Spending time with educators

who are doing this work on a daily basis provided a valuable perspective regarding

many of the issues and challenges that affect vocabulary instruction in the classroom.

A comprehensive review and examination of the data resulted in the

identification of four key assertions that are set forth in this chapter. For each

assertion, this researcher used interview responses and data collected from observing

teachers to provide a detailed explanation and supporting evidence. An analysis of

each assertion is also provided by this researcher. The findings and analysis reported

in this chapter seek to address the primary research question: How do the vocabulary

practices in a school’s K-3 classrooms align with research on vocabulary instruction?

Perceived Importance of Vocabulary Incongruent with Educator Knowledge

Vocabulary instruction at this school is mitigated by teachers' lack of

knowledge and training, though educators feel vocabulary plays an important role in

39

students’ lives. When asked to share their thoughts on vocabulary and vocabulary

instruction, teachers and administrators clearly stated their belief in its importance.

They spoke of its significance as it relates to reading and other content areas within the

academic setting as well as its potential to influence other spheres of life. However,

despite a collective belief in the importance of vocabulary and vocabulary instruction,

educators characterized their own knowledge of effective vocabulary practices as little

to none.

Educators with an administrative role spoke about the role of vocabulary from

a theoretical perspective, while teachers spoke of vocabulary in terms of its day-to-day

impact on their students. The district coach saw vocabulary as a social justice issue,

with schooling being a critical means of opening doors for underserved populations

and allowing students access to the language of power. The school principal saw

vocabulary as an issue of equity. She said that multiple and varied life experiences

provide an opportunity to develop and expand vocabulary, and students living in

poverty do not have access to the same experiences as students from higher

socioeconomic levels. In her opinion, this inequity starts before students come to

school and lack of vocabulary development limits students’ access to education. She

also said that school should play a big part in building kids’ vocabulary and that

vocabulary needs to be a priority in schools.

Teachers spoke of vocabulary more specifically, in terms of how vocabulary

knowledge affected their students in the classroom and in their students’ daily lives.

The first grade teacher said she felt like many things go over her students’ heads

40

because students are unfamiliar with certain words or are confused by context-specific

word meanings. First, second and third grade teachers all discussed the importance of

vocabulary knowledge in terms of reading. When first grade students are reading read

on grade-level they have moved beyond simple, repetitive text and are becoming

independent readers. The first grade teacher said at that point vocabulary plays a huge

role in text comprehension, and she believes students lose a big part of the overall

meaning of text when they do not understand individual word meanings. The second

grade teacher shared a similar belief, positing that what students do or do not know in

terms of vocabulary impacts comprehension; in her opinion, limited vocabulary also

affects students’ ability to decode new words and their overall reading. The third

grade teacher said she believed lack of vocabulary knowledge also affects students’

desire to read for pleasure.

Vocabulary knowledge influences areas outside of reading as well according to

the third grade teacher; she noticed a challenge when teaching new material (teachers

at this school use the California State Content Standards as the basis for instruction).

She stated that students who have not been exposed to very many words often struggle

to understand new standards-based material because they do not understand the

vocabulary in the units. She said an additional challenge arises when it is time for

assessments. Many of the third grade assessments at the school mirror the format of

the state tests (California Standards Tests), requiring students to read passages and

then correctly answer multiple-choice questions. The third grade teacher believes

many of her students understand the standard (class activities, discussions and

41

formative assessments during a unit provide information on student understanding) but

are unable to demonstrate their knowledge on the assessment; students cannot access

the text due to vocabulary limitations. In these cases, she said the students, “almost

don’t stand a chance.”

The teacher who saw the least impact in the classroom was at the kindergarten

level. She said that although she felt the role of vocabulary was “very, very

important” and many of her students’ knowledge was extremely low, she felt it

impacted students less when they were young. Kindergarten is a foundation for

academic education and in her opinion, vocabulary will become more important as

students get older and the curriculum becomes more difficult.

Despite strong beliefs in the importance of vocabulary and vocabulary

instruction, educators at this school site (from administrators to classroom teachers)

felt they lacked knowledge and training on effective vocabulary practices. This lack

of knowledge was present at the administrative level with the principal characterizing

her own level of knowledge regarding effective vocabulary practices as a 1 (on scale

of 1-10 with 10 being phenomenal). In her words, “It’s just not something I thought

about, even as a classroom teacher.” The district coach who had also served recently

as an elementary principal said he felt like he was “pretty solid” when he taught 4th6th grade in a dual immersion program, but said he is “definitely not an expert in

coaching vocabulary strategies, especially in kindergarten and first grade.”

The teaching staff also expressed an overall lack of expertise in the area of

effective vocabulary practices. The kindergarten teacher characterized her knowledge

42

as “a work in progress” stating that she felt more confident early in her career teaching

fourth graders, but since she has been teaching kindergarten and first grade the past

five years at this school she is not as well-versed. When the first grade teacher was

asked to characterize her knowledge of effective practices she was very candid. “I

have none, probably I got that in school, but that was a long times ago.” She said, “I

really feel like I know nothing about vocabulary instruction to be honest.” The second

grade teacher also referenced instruction from previous schooling saying she learned a

little about vocabulary practices in her teacher credential program, but it was “just part

of the curriculum.” She said the main way she taught vocabulary as a student teacher

was using a language arts curriculum, which provided a list of vocabulary words for

each unit and a series of activities that involved students interacting with the words.

She said there was usually a curriculum-provided vocabulary assessment at the end of

a unit. “When I came to [this district] I thought, ‘How do I teach vocabulary?’ and

there was no real answer.” The third grade teacher said her level of knowledge was

“not that good--not horrible, but not that good.”

Finding from these interviews represent a situation that could be characterized

as high will with low skill. Educators at this school believe strongly that vocabulary

knowledge plays a critical role in academic and life success and see education as an

important factor in building students’ knowledge. However, educators do not know

how to effectively teach vocabulary themselves. These findings indicate that while

belief and interest in vocabulary are a good foundation for building knowledge, they

do not necessarily translate to training and instruction for school educators.

43

Hemphill and Tivnan’s 2008 study of students in high poverty schools found

that “children’s vocabulary skills at the beginning of first grade made a critical

contribution to later achievement in reading comprehension” (p. 444). The researchers

also concluded that strong general literacy instruction (not specific to vocabulary) did

not change the reality that beginning vocabulary knowledge plays a critical role in

students’ reading growth. Given the importance of vocabulary, especially in the early

years, it is critical that administrators and teachers in primary grades translate their

belief in vocabulary into improving actual instruction.

Several of the teachers mentioned training in their credential programs or some

exposure to vocabulary instruction through a language arts curriculum during student

teaching, but there was little reference to recent training or resources once they were

actually teaching. Educators’ lack of knowledge at this school supports some

researchers’ beliefs regarding theory and practice. Blachowicz et al. (2006) said that

many diligent, motivated teachers are lacking the knowledge of how to provide

effective vocabulary instruction. Based on findings from this study, training in that

area may have to come from an outside source as neither the principal nor the school’s

district coach expressed confidence in their own knowledge of vocabulary instruction.

Effectiveness of Current Vocabulary Instruction is Unknown by School

Educators

Responses indicated educators either did not know if vocabulary instruction

was meeting student needs or did not think it was. Many educators said they did not

know how to evaluate the effectiveness of vocabulary instruction without specific

44

data. The following interview questions were asked to elicit discussion and insight