Archetypes of Wisdom

advertisement

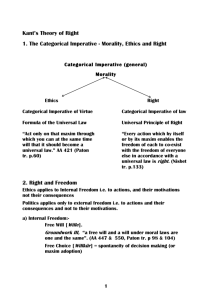

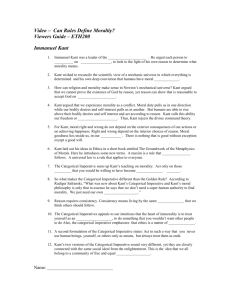

Archetypes of Wisdom Douglas J. Soccio Chapter 11 The Universalist: Immanuel Kant Learning Objectives On completion of this chapter, you should be able to answer the following questions: What is the difference between “nonmoral” and “immoral”? What is Kantian formalism? What is Critical Philosophy? What are phenomenal and noumenal reality? What are practical reason and theoretical reason? What is a maxim? What makes a maxim moral? What is a hypothetical imperative? What is the “practical imperative”? What is a thought experiment? What is the original position, and how is it related to the “veil of ignorance”? The Professor Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) was born in Königsberg in what was then known as East Prussia (now Kaliningrad in the former Soviet Union). His parents were poor but devout members of a fundamentalist Protestant sect known as Pietism, living severe, puritanical lives. At the age of sixteen, Kant entered the University of Königsberg. In 1755, he received the equivalent of today’s doctoral degree. He became a popular lecturer, and in 1770, the university hired him as a professor of logic and mathematics. The Solitary Writer Kant’s life is noteworthy for not being noteworthy, never traveling more than sixty miles from his birthplace, and living with a regularity that people in his town could “set their watches by.” But Kant was a prolific writer. His works include: The Critique of Pure Reason (1781) Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785) Critique of Practical Reason (1788) Critique of Judgment (1790) Religion Within the Limits of Reason Alone (1793) A Scandal in Philosophy Kant was one of the first thinkers to fully realize the consequences of Hume’s relentless attack on the scope of reason. However, the seeds of what Kant referred to as a “scandal” in philosophy were planted when Descartes doubted his own existence and divided everything into two completely distinct substances – minds and bodies. Kant felt something was drastically wrong if the two major schools (rationalism and empiricism) denied knowledge of cause and effect, denied existence of the external world, and rendered reason impotent in human affairs – while the science of the day clearly showed otherwise. Transcendental Idealism In response to this “scandal,” Kant turned to an analysis (or critique) of how knowledge is possible. In the process, he posited an underlying structure imposed by the mind on the sensations and perceptions it encounters. The theory he developed, transcendental idealism, claims that knowledge is the result of the interaction between the mind and sensation. Experience is shaped, or structured, by special regulative ideas called categories. Kant’s Copernican Revolution What Kant was proposing challenged assumptions about thought, in the same way Copernicus challenged assumptions about the universe. Kant suggested that instead of mind having to conform to what can be known, what can be known must conform to the mind. Phenomena and Noumena For Kant, our knowledge is formed by two things: our actual experiences and the mind’s faculties of judgment. This means that we cannot know reality as it is, but only as it is organized by human reason. Kant’s term for the world as we perceive it is phenomenal reality. His term for reality as it is independent of our perceptions – what we commonly call “objective reality” – is noumenal reality. Although we never experience pure reality, we can know that our minds do not just invent the world. Our minds impose order on the world, and that order is what Kant is trying to make explicit. Transcendental Ideas Though we cannot directly experience noumena, a class of transcendental ideas bridges the gap between things as we experience them and things as they are in themselves. Kant identified three transcendental ideas: Self Cosmos (totality) God These ideas create the unity and objectivity of your experience of yourself as “you” (in a world of sensation created by some higher intelligence). These transcendental ideas regulate and synthesize experience on a grand scale. Theoretical and Practical Reason Although there is only one faculty of understanding, Kant distinguishes two functions of reason: theoretical and practical. Theoretical reasoning is confined to the world of experience, and concludes that human beings, like all phenomena, are governed by cause and effect in the form of the inescapable laws of nature. Practical reasoning enables us to move beyond the phenomenal world to the moral dimension, helps us to deal with the moral freedom provided by free will, and produces religious feelings and intuitions. The Moral Law Within Kant notes that very few people consistently think of their own moral judgments as mere matters of custom or taste. Whether we actually live up to our moral judgments or not, we think of them as concerned with how people ought to behave. Just as we cannot think or experience without assuming the principle of cause and effect, Kant thought we cannot function without a sense of duty. The Moral Law Within Our practical reason imposes this notion of ought on us. For Kant, morality is a function of reason, based on our consciousness of necessary and universal laws. Since necessary and universal laws must be a priori, they cannot be discovered in actual behavior. The moral law is a function of reason, a component of how we think. The Good Will It is important to note that Kant conceives of the good will as a component of rationality, the only thing which is “good in itself.” Kant argues that “ought implies can” – by which he means it must be possible for human beings to live up to their moral obligations (since circumstances can prevent us from doing the good we want to do). Thus, Kant reasons, I must not be judged on the consequences of what I actually do, but on my reasons. Put another way, morality is a matter of motives. As Kant himself said, “Morality is not properly the doctrine of how we should make ourselves happy, but how we should become worthy of happiness.” Inclinations In Kantian terminology, decisions and actions are based on impulse or desire – or inclinations. Inclinations are unreliable and inconstant, and so not what morality should be based on. Inclinations are not produced by reason. Animals act from inclination, not from will. In contrast to inclinations, acts of will reflect autonomy, the capacity to choose clearly and freely for ourselves, without “outside” coercion or interference. Moral Duty Kant says, “Duty is the necessity of acting from respect for the moral law.” Duty does not serve our desires and preferences, but, rather, overpowers them. Such moral duty cannot be based on what an individual wants to do, what he or she likes or doesn’t like, or whether or not the individual cares about the people involved. Kant’s Imperatives Imperatives are forms of speech that command someone, or tell them what to do. Kant distinguishes two types of imperatives: hypothetical and categorical. Hypothetical imperatives tell us what to do under specific, variable conditions. They take the form, “If this, then do that.” The Categorical Imperative Categorical imperatives tells us what to do in order for our act to have moral worth. They take the form, “Do this.” The categorical imperative is universally binding on all rational creatures, and this alone can guide the good will (which summons our powers to obey such an imperative). The categorical imperative says, “Act as if the maxim of thy action were to become a universal law of nature.” In other words, we must act only according to principles we think should apply to everyone. The Kingdom of Ends Kant believed that as conscious, rational creatures, we each possess intrinsic worth, a special moral dignity that always deserves respect. In other words, we are more than mere objects to be used to further this or that end. Kant formulates the categorical imperative around the concept of dignity – sometimes referred to as the practical imperative. The Kingdom of Ends As Kant explains, “Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of another, never merely as a means but always at the same time as an end.” To describe the universe of all moral beings, Kant uses the expression,“kingdom of ends.” By this, Kant means a kingdom whose creatures possess intrinsic worth, in which everyone is an end in himself or herself. The Metaphysics of Morals Kant describes the metaphysics of morals as the transcendental realm that is universal and necessary for all creatures that are rational. The metaphysics of morals include: the transcendental ideas (of self, cosmos, and God) the division of reality into phenomena and noumena the moral law and duty our good wills have to abide by the categorical imperatives that ought to override our inclinations the kingdom of ends to which we all respectfully belong A Kantian Theory of Justice John Rawls relies upon some fundamental insights of Kant’s to generate a very powerful theory of justice. Rawls begins with a thought experiment known as the original position to justify two basic principles of justice. Rawls asks his readers to imagine that they are to found a society. What principles of justice would be chosen to regulate it? Principles chosen behind a “veil of ignorance” would be objective and impartial, and therefore, justified. A Kantian Theory of Justice Rawls argues that ultimately two principles would be chosen: 1) Everyone has an equal right to “the most extensive basic liberty compatible with a similar liberty for others.” 2) Any social and economic inequalities must be such that “they are both (a) reasonably expected to be to everyone’s advantage, and (b) attached to positions and offices open to all.” What about Family Justice? Susan Moller Okin argues that Rawls’s theory of justice contains gender biases in both the language and choice of examples. For example, Rawls does not provide an analysis of justice within the family. According to Okin, “Family justice must be of central importance for social justice.” What about Family Justice? Okin analyzes Rawls’s theory of justice with special attention to issues of gender and the family. According to Okin, Rawls’s analysis of justice is problematic because he rarely indicates “how deeply and pervasively gender-structured” society is. As Okin notes, “A feminist reader finds it difficult not to keep asking, ‘Does this theory apply to women?’” Discussion Questions How can we get a clearer sense of the power of the categorical imperative in order to clarify the nature of various forms of behavior? Formulate and then analyze the maxims that are required to justify contemporary issues in society, such as the following: Having unprotected sex without knowing if you are HIV positive. Forcing schools to teach the values of your religion. Chapter Review: Key Concepts and Thinkers Moral Nonmoral (amoral) Immoral Kantian formalism Critical philosophy Phenomenal reality Noumenal reality Theoretical reason Practical reason Hypothetical imperative Categorical imperative Practical imperative Principle of dignity Thought experiment Original position Veil of ignorance John Rawls (1921-2002) Susan Moller Okin (1946-2004)