Document

advertisement

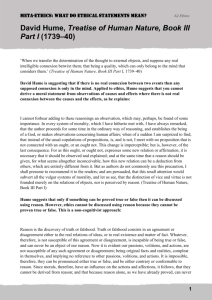

Justice in Hume’s Enquiry and Treatise NICOLE FICE Treatise 3.2.1 “…but that there are some virtues, that produce pleasure and approbation by means of an artifice or contrivance, which arises from the circumstances and necessities of mankind. Of this kind I assert justice to be…” 3.2.1.1. In consideration to the claim that justice is an artificial virtue, the structure of this section of the Treatise is organized as follows; First, he discusses motives and virtue. Here he also discusses duty and moral obligation. Second, he discusses motivation and justice He considers three natural motives, self-interest, public benevolence, and private benevolence as being potential motivators for justice. Third, he concludes from the above arguments that it cannot be the case that justice is a natural virtue, and defines the way in which it is instead an artificial virtue. Treatise: Motives and Virtue He begins by arguing that motivations are morally praiseworthy, and actions are not. “The external performance has no merit. We must look within to find the moral quality. This we cannot do directly; and therefore fix our attention on actions, as on external signs.” 3.2.1.2. “It appears, therefore, that all virtuous actions derive their merit only from virtuous motives, and are consider’d merely as signs of those motives. From this I conclude, that the first virtuous motive, which bestows a merit on any action, can never be regarded to the virtue of that action, but must be some other natural motive or principle. To suppose, that the mere regard to the virtue of the action, may be the first motive, which produc’d the action, and render’d it virtuous, is to reason in a circle. Before we can have such a regard, the action must be really virtuous, and this virtue must be deriv’d from some virtuous motive: And consequently the virtuous motive must be different from the regard to the virtue of the action. A virtuous motive is requisite to render an action virtuous. ” 3.2.1.4. Treatise: Motives and Virtue Con’t In the previous quote, I take Hume to be arguing two things: first, that deriving virtue from action itself is circular, and second, that to break this circle, we must conclude that virtuous motives are the source of virtuous action. “In short, it may be establish’d as an undoubted maxim, that no action can be virtuous, or morally good, unless there be in human nature some motive to produce it, distinct from the sense of duty.” 3.2.1.7. He appeals to a natural motive which produces virtuous action: in T 3.2.1.6 and EPM 2.2.1 Hume shows that this motive of human nature is benevolence. Treatise: Motives, Virtue, and Duty In his discussion on motives as being the source of virtuous action, Hume also argues that action from duty is distinct from motives 3.2.1.5, that is, duty is not a motive itself. “But may not the sense of morality or duty produce an action, without any other motive? I answer, it may: But this is no objection to the present doctrine. When any virtuous motive or principle is common in human nature, a person, who feels his heart devoid of that principle, may hate himself upon that account, and may perform the action without the motive, from a certain sense of duty, in order to acquire by practice, that virtuous principle…” 3.2.1.8. There are some people that have no sense of natural virtuous motive (benevolence), they perform ‘virtuous’ acts with no virtuous motivation, but instead from a sense of duty and moral obligation. But, from his previous arguments, said actions are not truly virtuous because they lack proper moral motivation; thus duty cannot be considered to a true motive for virtuous action. Treatise: Motivation and Justice He imagines someone lends him money, and when it comes time to pay it back, he questions the reasons he might have for doing so: “What reason or motive have I to restore the money? …that my regard to justice, and abhorrence of villainy and knavery, are sufficient reasons for me, if I have the least grain of honesty, or sense of duty and obligation. And this answer, no doubt, is just and satisfactory to man in his civiliz’d state, and when train’d up according to a certain discipline and education. But in his rude and more natural condition, if you are pleas’d to call such a condition natural, this answer wou’d be rejected as perfectly unintelligible and sophistical.” 3.2.1.9. Reference to Hobbes. In the state of nature, we would have no justice and no laws because they would have been unintelligible to the ‘savage’ (uneducated) man (also answered in 3.2.2.8). “Wherein consists this honesty and justice, which you find in restoring a loan, and abstaining from the property of others? It does not surely lie in the external action. It must, therefore, be plac’d in the motive, from which the external action is deriv’d. This motive can never be a regard to the honesty of the action. For ‘tis a plain fallacy to say, that a virtuous motive is requisite to render an action honest, and at the same time that a regard to the honesty is the motive of the action. We can never have a regard to the virtue of an action, unless the action be antecedently virtuous. No action can be virtuous, but so far as it proceeds from a virtuous motive. A virtuous motive, therefore, must precede the regard to virtue; and ‘tis impossible, that the virtuous motive and the regard to the virtue can be the same.” 3.2.1.9. Honesty, as an action, seems to lead to the circular reasoning we have previously explains. “’Tis requisite, then, to find some motive to acts of justice and honesty, distinct from our regard to the honesty; and in this lies the great difficulty.” 3.2.1.10. Treatise: Motivation and Justice Here Hume attempts to explore potential reasons or motivations for acts of honesty and justice. 3.2.1.11. (1) Motivation from regard to public interest. “First, public interest is not naturally attach’d to the observation of the rules of justice; but is only connected with it, after an artificial convention for the establishment of these rules, as shall be shown…” (2) Motivation from private benevolence & self-interest. “Secondly, if we suppose, that the loan was secret, and that it is necessary for the interest of the person, that the money be restor’d in the same manner…in that case the example ceases, and the public is no longer interested in the actions of the borrower; tho’ I suppose there is no moralist, who will affirm, that the duty and obligation ceases.” (3) Motivation from public benevolence. “Thirdly, experience sufficiently proves, that men, in the ordinary conduct of life, look not so far as the public interest, when they pay their creditors, perform their promises, and abstain from theft, and robbery, and injustice of every kind. That is a motive too remote and too sublime to affect the generality of mankind, and operate with any force in actions so contrary to private interest as are frequently those of justice and common honesty. Treatise: Motivation and Justice Motivation from public interest, private benevolence & self-interest (1) Regard to public interest is connected to justice, not the motivation of it. (2) On the motivation of self interest, Hume writes, “But ‘tis certain, that self-love, when it acts at its liberty, instead of engaging us to honest action, is the source of all injustice and violence.” 3.2.1.10. Self-interestedness can clearly not be the motivator of justice. Related to Hobbes. Private benevolence can also not motivate justice, because private matters differ from the concept of justice. 3.2.1.11. Private benevolence also fails to motivate justice because it does not really motivate one to be benevolent toward all of society; “Were private benevolence the original motive to justice, a man wou’d not be oblig’d to leave others in the possession of more than he is oblig’d to give them….” 3.2.1.14. Again, this focuses on property. If this is taken to be the motivator of justice, Hume says “it wou’d be a greater cruelty to dispossess a man of any thing, than not to give it to him.” 3.2.1.14. It fails to protect property, which is itself the primary goal of justice (see Annotation on p. 541). “…the chief reason, why men attach themselves so much to their possessions is, that they consider them as their property, and as secur’d to them inviolable by the laws of society.” 3.2.1.15. Treatise: Motivation and Justice Motivation from public benevolence (3) The notion that men should regard the greater interest of society in their moral motivations is not seen in the common motives and actions of individuals; Hume says it is too remote and distant a concern in every day life 3.2.1.11. “In general, it may be affirm’d, that there is no such passion in human minds, as the love of mankind, merely as such, independent of personal qualities, of services, or of relation to ourself. ‘Tis true, there is no human, and indeed no sensible, creature, whose happiness or misery does not, in some measure, affect us… But this proceeds merely from sympathy, and is no proof of such an universal affection to mankind.” 3.2.1.12. In addition, the love of mankind is motivated itself by sympathy. Treatise: Motivation and Justice Motivation from public benevolence He argues that a universal love among all human creatures would be similar to that of love between the sexes, which seems natural. This passion has its own symptoms, but also general ones; in love of between the sexes and of human kind, a good quality would both cause a stronger affection than the same degree of a bad quality would cause hatred, contrary to experience. We saw this is our previous discussions. Hume reminds us that “But in the main, we may affirm, that man in general, or human nature, is nothing but the object both of love and hatred, and requires some other cause, why which a double relation of impressions and ideas, may exist these passions. In vain wou’d we endeavour to elude this hypothesis. There are no phaenomena that point out any such kind affect to men, independent of merit… An Englishman in Italy is a friend: A European in China… But this proceeds only from the relation to ourselves, which in these cases gathers force by being confin’d to a few persons.” 3.2.1.12. From this, he reasons that public benevolence arises from a double relation of impressions and ideas, and is caused by a separate object; not necessarily one so general as the entirely of mankind. This cannot be the motivation of justice on the ground that it is a separate passion, and one that originates from the idea of self and individual objects. To argue that it should be the motivator of justice would be circular, I think. Treatise: Hume’s conclusions about Justice “From all this it follows, that we have naturally no real or universal motive for observing the laws of equity, but the very equity and merit of that observance; and as no action can be equitable or meritorious, where it cannot arise from some separate motive, there is an evident sophistry and reasoning in a circle. Unless, therefore, we will allow, that nature has establish’d a sophistry, and render’d it necessary and unavoidable, we must allow, that the sense of justice and injustice is not deriv’d from nature, but arises artificially, tho necessarily, from education, and human conventions.” 3.2.1.17. “Mankind is an inventive species; and where an invention is obvious and absolutely necessary, it may as properly be said to be natural as any thing that proceeds immediately from original principles, without the intervention of thought or reflection. Tho’ the rules of justice be artificial, they are not arbitrary. Nor is the expression improper to call them laws of nature; if by natural we understand what is common to any species, or even if we confine it to mean what is inseparable from the species.” 3.2.1.19. Justice, in the Treatise, is still a virtue, but an artificial one that arises from artificial necessity. Justice is not natural in the sense that it is motivated by our benevolence, but rather it is an artificial construction necessary to human life. Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals 3.1.1-21 The Enquiry gives a very different account of justice. He begins by stating that he will consider if the utility of justice is its sole foundation 3.1.1. He abandons the discussion of artificial virtue and merit that is seen in the Treatise. In order to how this, the Part 1 of Section 3 of the Enquiry is structured as follows; First, he experiments with the conditions of human society, and what effects these conditions would have on conceptions of justice, ultimately to examine the utility of justice. Second, he illustrates how the procedure of justice is justified. Third, Hume shows how the merit of justice is derived solely from its utility. Fourth, he makes mention of Hobbes, and responds to the problem of human nature. Fifth, Hume discusses The Role of “Inconveniences”, which Lorne has posted. Enquiry: Experiments on human society He begins with a thought experiment: “Let us suppose, that nature has bestowed on human race such profuse abundance of all external conveniences, that, without any uncertainty in the event, without care or industry on our part, every individual finds himself fully provided of whatever his most voracious appetites can want…” 3.1.2. What conception of justice would we have in this state? “It seems evident, that, in such a happy state, every other social virtue would flourish, and receive a tenfold increase; but the cautious, jealous virtue of justice would never once have been dreamt of.” He argues that justice would not have been invented in this state because it would have no utility. In addition, he adds, “For what purpose make a partition of goods, where everyone has already more than enough? Why give rise to property, where there cannot possibly be any injury? …Justice, in that case, being totally USELESS, would be an idea ceremonial, and could never possibly have place among the catalogue of virtues.” Par 3. It should be noted that Hume’s conception of justice seems to be fundamentally tied to conceptions of property. In a state where we have everything we could ever want we would not have a need for justice in this sense. “We see even in the present necessitous condition of mankind, that, wherever any benefit is bestowed by nature in an unlimited abundance, we leave it always in common among the whole human race, and make no subdivisions of right and property.” Par 3. He gives the examples of air and water as things being in given to humanity in infinite abundance, and things being shared among humanity. He argues it would make no sense to divide these things, at least, into objects of property. Enquiry “Again; suppose, that, tho’ the necessities of human race continue the same as at present, yet the mind is so enlarged, and so replete with friendship and generosity, that every man has the utmost tenderness for every man, and feels no more concern for his own interest than for that of his fellows: it seems evident, that the USE of justice would, in this case, be suspended by an extensive benevolence, nor would the divisions and barriers of property and obligation have ever been thought of.” 3.1.6. Given what was said in the Treatise, such an extensive benevolence is not conceivable. “Every man, upon this supposition, being a second-self to another, would trust all his interests to the discretion of every man; without jealousy, without partition, without distinction. And the whole race of mankind would form only one family; where all would lie in common, and be used, freely, without regard to property…” 3.1.6. Even if the extensive benevolence to all human kind were possible, Hume argues that it would not form a conception of justice, like in the pervious experiment. Again he argues that this great public benevolence is not really possible; he notes that only families come close to maintaining this sort of benevolence (3.1.7). He also argues that, even if the greater society of men could become like a family (he also gives examples of similar attempts), they would quickly resort back to selfishness and desire their own property, and thus they would adopt anew the conception of justice (3.1.7). He uses these examples to conclude that justice is derived from its utility; “So true is it, that that virtue derives its existence entire from its necessary use to the intercourse and social state of mankind” 3.1.7. We see here that utility is the sole motivator of justice. The arguments here are similar to the ones in the Treatise in regards to public benevolence, but Hume abandons the discussion of the motive of justice, and instead focuses on the utility of justice. Enquiry Now he considers the reverse of the experiment, where everyone is in a state of misery, poverty, and war 3.1.8. He argues again that “It will readily, I believe, be admitted, that the strict laws of justice are suspended, in such a pressing emergence, and give place to the stronger motives of necessity and self-preservation.” 3.1.8. Here he gives the example of looting a shipwreck. Another example of a besieged city. “…can we imagine, that men will see any means of preservation before them, and lose their lives, from a scrupulous regard to what, in other situations, would be the rules of equity and justice? The USE and TENDENCY of that virtue is to procure happiness and security, by preserving order in society: But where the society is ready to perish from extreme necessity, no greater evil can be dreaded from violence and injustice; and every man may now provide for himself, by all the means, which prudence can dictate, or humanity permit.” 3.1.8. In this warring and chaotic condition of society, Hume argues that we would also abandon justice and resort to survival. Similar to Hobbes’ conception of humans in the state of nature… He gives another example of a virtuous man in a ‘society of ruffians’, where he would be forced to abandon his conceptions of virtue and justice in order to simply survive. “And his particular regard to the justice being no longer of USE to his own safety or that of others, he must consult alone the dictates of self-preservation, without concern for those who no longer merit his care and attention.” 3.1.9. In 3.1.11 Hume gives the example of war… Enquiry: Procedure of Justice He kind of pauses his experiments to say, “When any man, even in political society, renders himself, by his crimes, obnoxious to the public, he is punished by the laws in his goods and person; that is, the ordinary rules of justice are, with regard to him, suspended for a moment, and it becomes equitable to inflict on him, for the benefit of society, what, otherwise, he could not suffer without wrong or injury.” 3.1.10. He considers the procedure of justice in a regular state. Here he explains the procedure of justice. That, when someone commits a crime, it is justified to withhold their own rights to equity and justice in order to punish him; this is for the greater benefit of society. Thus, justice in justified because it provides a utility to the society. Enquiry: Justice as utility “Thus the rules of equity or justice depend entirely on the particular state and condition, in which men are placed, and owe their origin and existence to that UTILITY, which results to the public from their strict and regular observance. Reserve, in any considerable circumstance, the condition of men: Produce extreme abundance or extreme necessity: Implant in the human breast perfect moderation and humanity, or perfect rapaciousness and malice: By rendering justice totally useless, you thereby totally destroy its essence, and suspend its obligation upon mankind.” 3.1.12. Justice is inconceivable without its utility. “The common situation of society is a medium amidst all these extremes… We are naturally partial to ourselves, and to our friends; but we are capable of learning the advantage resulting from a more equitable conduct. Few enjoyments are given us from the open and liberal hand of nature; but by art, labor, and industry, we can extract them in great abundance. Hence the ideas of property become necessary in all civil society: Hence justice derives its usefulness to the public: And hence alone arises its merit and moral obligation.” 3.1.13. The argument is such that, insofar as society is a median between extreme abundance and extreme poverty, and there is no great public benevolence, justice exists because of and derives its merit from the utility it has. Its goal is to protect individual property, and in doing so, it becomes useful. This utility is also derived from the ability of justice to punish those who commit crimes, and thus it keeps individual property protected (which is the primary aim of justice). Keep in mind that this is different from the Treatise because it makes no mention of the motives of justice nor what it means for justice to be an artificial virtue. Enquiry: Hobbes He makes mention of Hobbes; “This poetical fiction of the golden age is, in some respects, of a piece with the philosophical fiction of the state of nature; only that the former is represented as the most charming and most peace-able condition, which can possibly be imagines; whereas the latter is painted out as a state of mutual war and violence…” 3.1.15. Hume also responds to Hobbes. “Whether such a condition of human nature could ever exist, or if it did, could continue so long as to merit the appellation of a state, may justly be doubted. Men are necessarily born in a family-society, at least; and are trained up by their parents to some rule of conduct and behaviour. But this must be admitted, that if such a state of mutual war and violence was ever real, the suspension of all laws of justice from their absolute in-utility, is a necessary and infallible consequence.” 3.1.16. Justice would not exist in the Hobbesean state of nature. Note the importance of education here and in the Treatise. Here, Hume notes that (unlike Hobbes) there has always existed some sort of state-like entity; that being the family. And in this family, you learn behavioural norms. Thus, the state of nature, as Hobbes conceives of it, could never exist because people always have had some underlining education of moral behaviours and rules of justice. Enquiry: Paragraphs 17-21 See Lorne’s post on the website…