Aristotle on virtue

advertisement

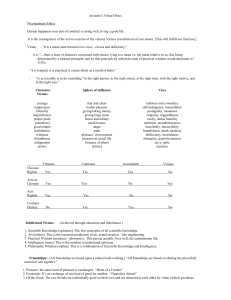

Aristotle on virtue Michael Lacewing enquiries@alevelphilosophy.co.uk Virtue • A virtue (arête) is a trait of mind or character that helps us achieve a good life (eudaimonia) – Intellectual virtues – Moral virtues (traits of character) What is a moral virtue? • Aristotle: a moral virtue is a state of character by which you ‘stand well’ in relation to your desires, emotions and choices: – A character trait is a disposition relating to how one feels, thinks, reacts etc. in different situations, e.g. short-tempered, generous – A virtue is a disposition to feel, desire and choose ‘well’ The doctrine of the mean • Virtues and virtuous actions lie between ‘intermediate’ between two vices of ‘too much’ and ‘too little’ – Compare eating too much/little • Not arithmetical – ‘to feel [desires and emotions] at the right times, with reference to the right objects, towards the right people, with the right motive, and in the right way’ • This is Aristotle’s ‘doctrine of the mean’ • But this is not the same as ‘moderation’ on all occasions Practical wisdom • Practical wisdom – an intellectual virtue – helps us know what the right time, object, person, motive and way is – To feel ‘wrongly’ is to feel ‘irrationally’ • A virtue, then, ‘a state of character concerned with choice, lying in the mean, i.e. the mean relative to us, this being determined by a rational principle, and by that principle by which the person of practical wisdom would determine it’ Virtues and vices Passion/concern Vice of deficiency Fear Cowardly Virtue Vice of excess Courageous Rash Pleasure/pain ‘Insensible’ Temperate Self-indulgent Money Mean Liberal (‘free’) Prodigal Important honour Unduly humble Properly proud Vain Small honours ‘Unambitious’ ‘Overambitious’ Anger ‘Unirascible’ ‘Properly ambitious’ Good-tempered Pleasant to others Shame Quarrelsome Friendly Obsequious Shy Modest Shameless Attitude to other’s fortune Spiteful Righteously indignant Envious Short-tempered Acquiring virtues • We acquire virtues of character through the habits we form during our upbringing. – Virtues can’t simply be ‘taught’ – there are no moral child prodigies • We are not virtuous ‘by nature’, but become virtuous by practising – Like learning to play a musical instrument – So we become just by doing just acts Virtuous action • How can we do just acts unless we are already just? – ‘in accordance with’ justice vs. fully just acts • A fully virtuous action – know what you are doing – choose the act for its own sake – choose from a firm and unchangeable character • As we become just, we understand what justice is and choose it because it is just Two contrasts • Is strength of will virtuous? – Aristotle: No. A virtuous person doesn’t have to overcome temptation. • Is eudaimonia the moral life? – Aristotle’s idea is wider, e.g. we should have ‘proper pride’ and seek honour (vs. Christian humility and self-sacrifice)