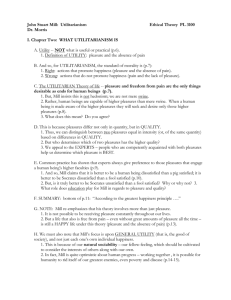

Archetypes of Wisdom

advertisement

Archetypes of Wisdom Douglas J. Soccio Chapter 12 The Utilitarian: John Stuart Mill Learning Objectives On completion of this chapter, you should be able to answer the following questions: What is psychological hedonism? What is ethical hedonism? What is the principle of utility? What is simple utilitarianism? What is the “Hedonic Calculus”? What is the Greatest Happiness Principle? What is the “Egoistic Hook”? What is refined utilitarianism? What is altruism? Social Hedonism Modern utilitarianism developed as a response to social conditions created by the Industrial Revolution, which created a class of workers whose jobs were repetitious, dangerous and poorly paid (i.e., degrading and dehumanizing). Hordes of workers sought work in the mill towns and cities, creating large slums. High rents resulted in overcrowding, as poorly paid workers lived two and three families to an apartment. Thomas Malthus In 1798, Thomas Malthus (1766-1834), an Anglican minister, wrote An Essay on the Principle of Population as It Affects the Future Improvement of Society. He relayed grave doubts about the feasibility of social reform. He said that food production increases arithmetically, but unchecked population growth progresses geometrically. Troubled by growing slums, he said the only way to avoid harsh “natural cures” like wars and epidemics was to stop helping the poor and remove all restraints on the free enterprise system. The law of supply and demand would make it difficult for the poor to marry early or support many children, thereby checking the rapid rise in population growth. Philosophy and Social Reform It was in this context that Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) directly challenged the owners, bosses, and ruling classes when he insisted that “each counts as one and only one.” Bentham criticized those in power for pursuing their own narrow, socially destructive goals, instead of pursuing happiness for everyone. His solution was to establish democratic rule by the whole society, rather than by a select class. For Bentham, the legitimate functions of government are social reform and the establishment of the conditions most conducive to promoting the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. The Principle of Utility Bentham attempted to base his philosophy on careful observation of social conditions and actual human behavior. Like Aristippus before him, Bentham saw that pain and pleasure shape all human activity. In An Introduction to Principles of Morals and Legislation, he introduces the principle of utility, to “act always to promote the greatest happiness for the greatest number.” Sometimes referred to as the pleasure principle, the principle of utility uses psychological hedonism (that pain and pleasure determine what we do) to develop an ethical hedonism (that these alone point to what we ought to do). The Hedonic Calculus Bentham wanted to make ethics a science. He formulated the hedonic calculus, introducing mathematical precision to the difficult task of weighing alternative courses of action. For this, Bentham proposed “units” of pleasure or pain, called “hedons” (today often referred to as “utiles”). When contemplating an action, one calculates the pleasure and pain for those affected in terms of seven elements. Bentham believed each of us already uses hedonic calculation on an intuitive level, and that he was simply adding scientific rigor to our informal methods of choosing pleasure and avoiding pain. The Hedonic Calculus In Bentham’s hedonic calculus, he identified four elements that affect pleasure or pain themselves. Two affect the action related to pleasure or pain, and one is based on the number of people affected. The seven elements are: 1. Duration: How long will the pleasure last? 2. Propinquity: How soon will the pleasure occur? 3. Certainty: How likely or unlikely is it that the pleasure will occur? 4. Fecundity: How likely is it that the proposed action will produce more pleasure? 5. Intensity: How strong is the pleasure? 6. Purity: Will there be pain accompanying the action? 7. Extent: How many other people will be affected? The Question is, Can They Suffer? Bentham extended the ethical reach of the pleasure principle beyond the human community to include any creature with the capacity to suffer. Bentham rejected any notion that animals lack moral worth simply because they cannot reason. In this, Bentham disagreed with Descartes, whose dualism led him to conclude that animals are soulless, and so, not members of the moral community. But for Bentham, “The question is not, Can they reason? nor Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?” John Stuart Mill John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) is one of the most interesting figures in philosophy. His parents were estranged; his father was unfeeling. His destiny was sealed when Bentham befriended his father, and the two developed a rigorous education for John Stuart, carefully planned to produce a champion of utilitarianism. John Stuart Mill When he was twenty, Mill began to pay the high price of his hothouse education in earnest with a depression or breakdown he described as a “dry heavy dejection.” Mill later blamed the strict environment in which he was raised of robbing him of his feelings. But aided by his superior intellect, Mill was eventually able to pull himself out of his depression and develop a fuller and deeper insight into the the human condition than his two teachers ever knew. Mill on Women’s Rights Mill’s rigid training was also softened by his remarkable relationship with Harriet Taylor. After her first husband’s death, the two were married (fifteen years after they met). She lived only another seven years, but Mill credited her with improving his work for the better, saying, “the properly human element came from her.” One great effect she had was in the area of women’s rights, leading Mill to write “On The Subjection of Women,” and to become an advocate of rights for that half of the population that had been hitherto denied a natural environment in which to flourish. Refined Utilitarianism Mill could not accept Bentham’s simple version of hedonism, leveling all pleasures as Aristippus had done. Bentham failed to assign higher importance to moral, intellectual, or emotional pleasures. By introducing the notion of quality into utilitarianism, Mill refuted the orthodoxy he had been raised to defend. Most significant was Mill’s declaration that all pleasures are not, in fact, equal. Mill argued that there are empirical grounds for asserting that what we might call “refined pleasures” are preferable to the “cruder pleasures.” Altruism and Happiness Mill asserts that utilitarianism ultimately rests on “the social feelings of mankind, the desire to be in unity with our fellow creatures.” Altruism – from the Latin alter, or “other” – is the capacity to promote the welfare of others. Altruism stands in clear contrast to egoism – no individual’s self-interest is more or less important than any other’s self-interest. The function of education is twofold: 1) to instill the skills and knowledge necessary for an individual to live well and productively, and 2) to create healthy, altruistic citizens. But the second part requires that education become a lifelong activity, with people having the opportunities and an environment conducive to that development. Happiness and Mere Contentment Mill was not content with merely modifying behavior. He wanted to reform character, too. In this regard, he distinguished between happiness and “mere contentment.” Mere contentment is a condition of animals and those unfortunate people limited to enjoying lower pleasures. A major goal of Mill’s utilitarianism is to make as many people as possible happy, rather than just content. Mill believed that happiness requires a balance of tranquility and excitement. Selfishness – the principle cause of unhappiness – robs us of both. Mill’s Persistent Optimism According to Mill, the chief task of all right-thinking, wellintentioned people is to address the causes of social misfortune. From Mill’s (and Bentham’s) concern for society, we have acquired the concept of public utilities, welfare regulations, and mandatory minimum education laws. Mill also argued that liberty of thought and speech are absolutely necessary for the general happiness, since we can determine the truth only through an ongoing clash of opinions. He worried about what has been called “the tyranny of the majority,” and warned against assigning too much weight to majority beliefs. Mill’s Persistent Optimism In the end, Mill remained an optimist. He maintained that by applying reason and good will, the vast majority of human beings could live with dignity, political and moral freedom, and a harmonious happiness. He believed that “the wisdom of society” could extinguish poverty, and that well-intentioned science could alleviate many other problems. Discussion Questions How does Mill distinguish between happiness and contentment? Why is this distinction vital to his utilitarian philosophy? What role does education play here? Has your education lived up to Mill’s hopes? If yes, in what ways? If no, why not? Chapter Review: Key Concepts and Thinkers Psychological Hedonism Ethical Hedonism Principle of Utility Altruism John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832)