File - Human Development

advertisement

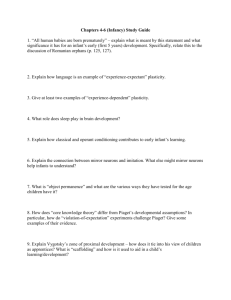

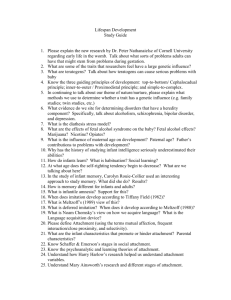

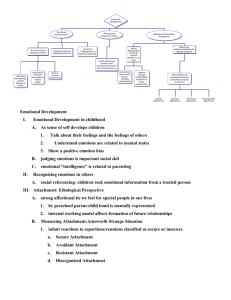

Child Development: Chapter 10 Emotional Development and Attachment Chapter Outline Emotions: Universality and Difference Attachment Development of Emotions Normal Emotions and Emotional Problems Emotions: Universality and Difference Although our basic emotions appear to be biologically determined, we quickly develop ways of thinking about emotions, called emotion schemas, that affect how we experience and show emotions. Emotion schemas differ by culture, gender, personality and other factors. Cultural differences affect both the display and the interpretation of emotions. Temperament The general emotional style an individual displays in responding to events. Chess and Thomas’s types of temperament. Easy: positive mood, easy adaptation to change, and regularity and predictability in patterns of eating, sleeping, and elimination. Difficult: more negative mood, frustration and intense responses, slow adaptation to change, and irregular patterns of eating, sleeping, and elimination. Slow-to-warm: slow adaptation to new experiences and moderate irregularity in eating, sleeping, and elimination. Attachment Secure attachment can be defined as a strong, positive emotional bond with a particular person. You turn to that person for comfort. You are usually happy to see that person and may be unhappy about separations. This is a person with whom you can feel free to “be yourself” in the fullest sense. Attachment and Adaptation Attachment is adaptive because it allows the infant to feel secure Infant behaviors are designed to keep the parent nearby to satisfy needs When infants and toddlers feel secure they can explore, which leads to learning Safe base for exploration: Child feels safe to explore while parent is there. Goes back for hugs: “emotional refueling” The History of the Study of Attachment Freud and behaviorism are both drive reduction theories. Hunger is a drive that is satisfied by food from the mother. Behaviorism – classical conditioning of the mother (neutral stimulus) with the food (unconditioned stimulus) to produce satisfaction. Freud – baby develops a cathexis of the mother because of the food she provides. Therefore, feeding causes attachment. Development of the Ethological Point of View HOWEVER, Harry Harlow’s research on monkeys showed otherwise: http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=898770 8960769531225&q=harlow%27s+monkey&total= 13&start=0&num=10&so=0&type=search&plinde x=1 John Bowlby’s Stages of the Development of Attachment Preattachment (birth to 6 weeks): sensory preferences, social smile Attachment in the making (6 weeks to 6-8 months): stranger anxiety Clear-cut attachment (6-8 months to 18 months-2 years): separation anxiety Goal corrected partnership or Formation of reciprocal relationships (18 months on) Development of internal working models Mary Ainsworth’s Strange Situation Mother and baby enter a comfortable room (equipped with a oneway mirror so they can be observed) with the stranger, who immediately leaves. Baby plays while mother responds naturally. Stranger enters, and at the end of 3 minutes the mother leaves. Baby is in the room with the stranger, who may interact with the baby. Mother returns, stranger leaves, and at the end of 3 minutes the mother again leaves. Baby is alone for 3 minutes. Stranger enters and may interact with the baby. Mother returns. (Ainsworth & Bell, 1970) Ainsworth’s Categories of Attachment Secure attachment anxious avoidant attachment anxious ambivalent attachment disorganized/disoriented attachment Behavior during strange situation Attachment is a relationship Mother – responsiveness to the baby’s needs What helps mothers to be responsive? A positive relationship with their partner Adequate economic resources Good psychological health (for example, maternal depression has been linked to insecure attachment) A history of good care in their own childhood An infant who is easy to care for Father Supports mother emotionally, maybe financially Forms secure attachment with infants as well Baby Temperament affects type of attachment Medical factors may play a role Colicky babies are difficult It’s a Complicated Picture Infant negative emotionality (intense and frequent crying) Less sensitive mothering when the babies were 6 mos. old More insecure attachment at 1 year (Crockenberg, 1981; Sroufe, 2005). BUT, this relationship only held when mothers were at risk from poverty, inadequate social support, or a history of parental rejection. Mothers who were not at risk were often more involved with their fussy babies. (Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2003). Attachment: Biology Children raised by their parents from birth experience a rise in oxytocin after interacting with their parents, while neglected, orphaned children who are adopted do not show this rise. Oxytocin is linked with a positive feeling that arises in connection with warm social interactions (Carter, 2005). Many neglected children produce low levels of vasopressin, a hormone that is linked with the ability to recognize individuals as being familiar. Children reared in deprived situations are more likely to run to any available adult when distressed or withdraw from all adults. It is not yet clear whether these chemical responses are set for life or can change with life experiences. Attachment and Culture In most countries, 2/3 of infants have secure attachment. What do different cultures define as sensitive parenting? For example, what is good parenting when your infant cries every hour through the night while all their needs have already been cared for? American mothers tend to see this behavior as testing the limits and asserting one’s self. Japanese mothers are more likely to see this as a need for closeness or interdependence. How is maternal behavior likely to differ based on these two different interpretations? The impact of early attachment and later experiences The myth of bonding Long-term outcomes of infant attachment Impact of Later Experiences An indirect link between early attachment and the ability to have intimate, romantic relationships in early adulthood. Secure attachment in infancy prepares the child for later positive peer relationships The child’s history with peer relationships independently predicts some aspects of adult relationships The combination of early attachment and later experiences with peers was even more predictive of some aspects of later romantic relationships. Each stage provides the foundation for the next stage, but experiences at each successive stage also change the nature and direction of a child’s development. Romantic Attachment Styles Reactive Attachment Disorders Inhibited type: inability to form any attachments Disinhibited type: indiscriminant attachments to anyone Prevention and Treatment The most effective therapies focused on developing the mother’s sensitivity to her baby. Therapy that involved both mothers and fathers had even greater effect For adopted children with attachment disorders, it is important for a family to know that much hard work will be needed to try to reverse the child’s earlier experiences. Development of Emotions Understanding and recognition of basic emotions develops before awareness of selfconscious emotions. Basic emotions: happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise/interest, and disgust Self-conscious emotions: those that depend on awareness of oneself, such as pride, guilt, and shame. Empathy and Sympathy Empathy: sharing the feelings of other people. Sympathy: concern for others’ welfare that often leads to helping or comforting them Social Referencing Social referencing: using the reaction of others to determine how to react in ambiguous situations Representation of emotions Labeling and discussion of emotions with young children helps them to cope with stressful situations. Regulation of emotions Infants – soothed by caregivers; also develop ways to soothe themselves: thumb sucking, holding a favorite “blankie,” or avoidance of something by looking away Preschoolers – those with more able to regulate their emotions had higher academic ability in third grade and higher social competence in adolescence and adulthood (Mischel & Ayduk, 2004; Izard, 2007). Emotional intelligence: Understanding and controlling one’s own emotions, understanding those of others, and being able to use all of this understanding to navigate human interactions successfully Daniel Goleman (1995) believes that the ability to deal with emotions is of equal importance to our academic success as our cognitive abilities. Normal emotions and emotional problems Emotions are normal reactions to events in our lives. Sometimes emotions go beyond adaptive response and interfere with ongoing development for children and adolescents. Fear and Anxiety Fear: response to something specific Anxiety: a vague sense of fear or a feeling of dread. Development of Fear Fear of things like loud noises or novel items along with stranger and separation anxiety appear during the end of the first year of life. Toddlers and preschoolers experience fear of the dark or of monsters in the closet, linked with fantasy. Fears increase through age 8 and then recede. Anxiety disorders A level of anxiety that interferes with normal functioning; includes separation anxiety disorder in older children or adolescents, generalized anxiety disorder, and social phobias. Sadness and depression Sadness is a normal response to loss and disappointment. Depression goes beyond sadness to feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness, a lack of pleasure, sleep and appetite disturbances, and possibly suicidal ideas or plans. Depression is more common in teens than younger children and in adolescent girls than in adolescent boys. Anger and Aggression Most children learn to control their anger by channeling it in appropriate ways. However, some children are not able to control feelings that lead them into conflict with others. Most often higher levels of aggression in younger children decline as the children get older. For a small subgroup levels of aggression remain high. Conclusion From earliest infancy onward, we learn to understand, express, and control our emotions. Emotional experiences develop within the context of our close relationships with other people. At each stage of development we add new levels of understanding and experience that build upon each other to shape the nature of our feelings about others and about ourselves.