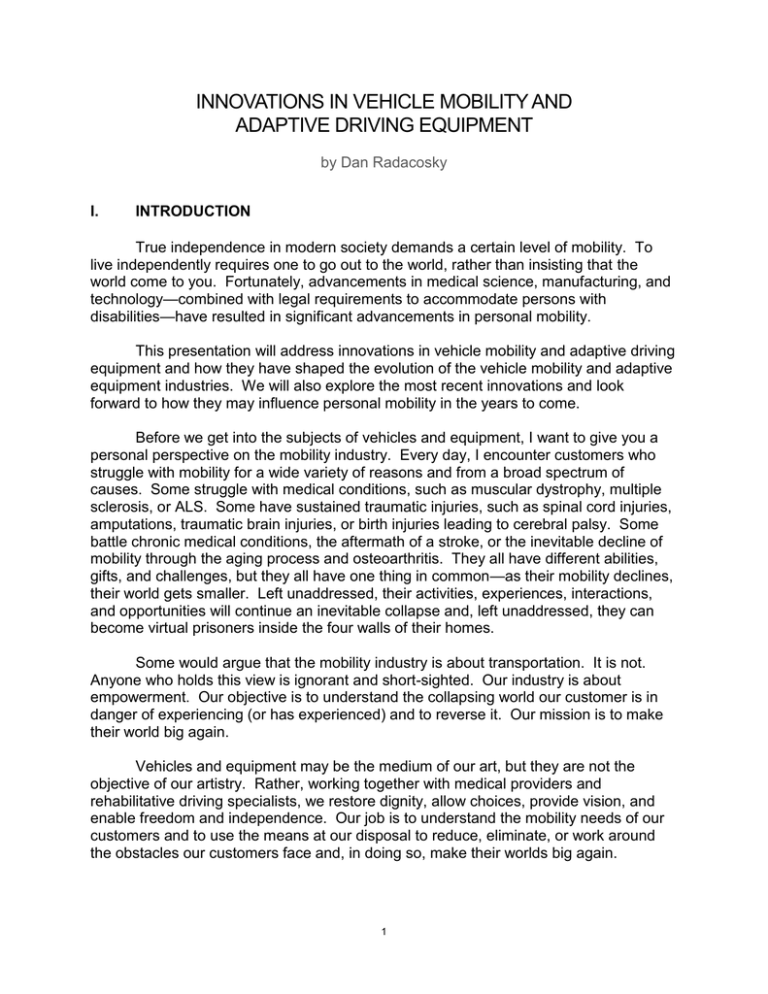

INNOVATIONS IN VEHICLE MOBILITY AND

ADAPTIVE DRIVING EQUIPMENT

by Dan Radacosky

I.

INTRODUCTION

True independence in modern society demands a certain level of mobility. To

live independently requires one to go out to the world, rather than insisting that the

world come to you. Fortunately, advancements in medical science, manufacturing, and

technology—combined with legal requirements to accommodate persons with

disabilities—have resulted in significant advancements in personal mobility.

This presentation will address innovations in vehicle mobility and adaptive driving

equipment and how they have shaped the evolution of the vehicle mobility and adaptive

equipment industries. We will also explore the most recent innovations and look

forward to how they may influence personal mobility in the years to come.

Before we get into the subjects of vehicles and equipment, I want to give you a

personal perspective on the mobility industry. Every day, I encounter customers who

struggle with mobility for a wide variety of reasons and from a broad spectrum of

causes. Some struggle with medical conditions, such as muscular dystrophy, multiple

sclerosis, or ALS. Some have sustained traumatic injuries, such as spinal cord injuries,

amputations, traumatic brain injuries, or birth injuries leading to cerebral palsy. Some

battle chronic medical conditions, the aftermath of a stroke, or the inevitable decline of

mobility through the aging process and osteoarthritis. They all have different abilities,

gifts, and challenges, but they all have one thing in common—as their mobility declines,

their world gets smaller. Left unaddressed, their activities, experiences, interactions,

and opportunities will continue an inevitable collapse and, left unaddressed, they can

become virtual prisoners inside the four walls of their homes.

Some would argue that the mobility industry is about transportation. It is not.

Anyone who holds this view is ignorant and short-sighted. Our industry is about

empowerment. Our objective is to understand the collapsing world our customer is in

danger of experiencing (or has experienced) and to reverse it. Our mission is to make

their world big again.

Vehicles and equipment may be the medium of our art, but they are not the

objective of our artistry. Rather, working together with medical providers and

rehabilitative driving specialists, we restore dignity, allow choices, provide vision, and

enable freedom and independence. Our job is to understand the mobility needs of our

customers and to use the means at our disposal to reduce, eliminate, or work around

the obstacles our customers face and, in doing so, make their worlds big again.

1

II.

VEHICLE MOBILITY

If you doubt the significance of vehicle mobility in modern society, try giving up

your car for a week. You will become acutely aware of the challenges, inconveniences,

limitations, and time-drains that persons with disabilities face every day. If you dare

allow yourself the notion that public transportation is the substantial equivalent of being

able to come and go in your own vehicle, try it. Even in urban areas with the best public

transportation systems, you will discover that public transportation is barely adequate

when the seasons and weather conditions are favorable. When the season and/or the

weather turns inclement, you will realize that relying on public transportation is

burdensome.

In modern American society, we rely on our vehicles to accomplish even the bare

necessities of life. But to experience the true range of choices and freedom for career,

entertainment, dining, and travel, our own vehicles are essential. This underscores the

critical nature of bringing vehicle mobility to persons with disabilities.

A.

The Birth of an Industry

Ralph Braun is widely acknowledged to be the founder of the vehicle mobility

industry. Ralph took his own personal disability, combined it with his ingenuity and

vision, and created a better world for himself and others. From Ralph’s humble

beginnings, the modern mobility and adaptive equipment industries were born—

reaching levels of sophisticated engineering, manufacturing, and technology that he

likely never imagined at the outset. His objectives—to make a motorized wheelchair

and to make a vehicle accessible for a wheelchair user—became the inspiration to look

at vehicle mobility for the disabled in an entirely different light.

B.

Full Size Vans

Full size vans morphed from hippie conversions lined with shag carpeting to

mobility vehicles for one simple reason—interior space. The full size van was small

enough to be a practical form of everyday transportation, but large enough to allow for

adaptation for wheelchair users to enter and maneuver inside the vehicle. Therefore,

equipping full size vans with wheelchair lifts became the standard method of vehicle

mobility for wheelchair users.

Further innovations in this genre of mobility vehicle included lowered floors,

raised roofs, and raised doors. These variations provided the flexibility to fit taller

wheelchair users in motorized wheelchairs (power chairs) into vans, thereby expanding

the user base and, for vehicle converters, the size of the market.

C.

The Lowered-Floor Minivan

Without question, the most significant historical innovation in vehicle mobility has

been the side-entry, lowered-floor minivan. The standard side-entry minivan conversion

2

includes a lowered floor, a ramp system, a "kneeling" (lowering) system, and removable

front seats. Lowered floor minivans provide maximum flexibility in configuration,

allowing wheelchair users to set up the vehicle as a driver, a front passenger, or a

center passenger. The rear bench seat maintains adequate seating capacity for

families, as well.

Advancements in this type of conversion now allow sufficient door and interior

height to accommodate tall power chair users who, just a few years ago, would have

been limited to a full size van. These smaller vans are easier to drive and park for

disabled drivers, and provide the option for a wide variety of creature comforts through

the various trim levels offered by the original van manufacturers. Moreover, technology

incorporated by automobile manufacturers has advanced significantly in recent years,

often alleviating the need for certain adaptive equipment due the presence of features

such as standard backup cameras, blind spot monitors, and radar collision avoidance

systems.

Because they can accommodate the broadest range of wheelchair users as

drivers, and because they provide the most configuration options, the lowered floor

minivans continue to be the industry mainstay.

Rear-entry conversions provide a lower-cost alternative to fully automatic, sideentry conversions. The tradeoffs, however, are limited configuration options and the

unsuitability for wheelchair users who need or want to drive from their wheelchairs. The

rear-entry style lowered-floor minivan has gained widespread acceptance in the

commercial transportation (taxicab) industry.

D.

Other Vehicle Types

In recent years, there has been a growing demand for conversions of other types

of vehicles--SUVs, pick-up trucks, and other types of crossover vehicles. Each of these

types of conversions provides choices to the wheelchair user that were not previously

available. Each, likewise, has its unique, inherent limitations that must be taken into

account in determining whether a specific vehicle conversion is suitable for a particular

wheelchair user. The main challenges are limited configuration and interior

maneuverability due to smaller floor footprints. However, advancements in engineering,

technology, and manufacturing continue to broaden the landscape of consumer choices

in mobility vehicles, and this trend figures to continue in the coming years.

One word of warning—ask before you buy. The recent automotive trend toward

“greener” vehicles (hybrids, electrics, subcompacts, and the like) creates a very real

opportunity to make a $40,000, $50,000, or $60,000 mistake. As the industry trends

toward smaller and lighter, the resulting vehicle designs are not necessarily compatible

with the realistic needs of the disabled driver. Many of the “green” vehicles will not

support a hitch, a lift, or even the size or weight of a power chair. The role of the

mobility adviser and the driver evaluator (Certified Driver Rehabilitation Specialist or

CRDS) is to make a professional assessment of whether a particular vehicle is

3

compatible with a disabled driver's needs, taking into account their unique abilities and

equipment requirements.

III.

ADAPTIVE DRIVING EQUIPMENT

A.

Assistive Seating

One of the first issues that arises for many people as their mobility declines is the

inability to get in and out of a standard car seat. This has led to a variety of innovations

that we can generically include in the topic of assistive seating. There are seats that

literally come out of the vehicle to assist a driver or passenger to get in and out of the

vehicle. These are designed as a first measure of mobility assistance, as they are

intended largely to be used in unconverted vehicles. They are often referred to as

"turny" or "valet" seats--a testament to the fact that the Autoadapt Turny® seat line and

the Bruno Valet® seat line have become the gold standards of the industry. These are

considered historically innovative because they allow persons with declining mobility to

remain in a stock vehicle for a longer period of time.

As loss of mobility tends to be progressive in nature, there comes a time when a

vehicle converted for wheelchair accessibility becomes necessary. For many of these

people, a six-way transfer seat is necessary to enable them to transfer from their

wheelchair or scooter onto the driver's or front passenger's seat. They are referred to

as "six-way" transfer seats because they have controls that allow the seat base to be

adjusted up and down (higher and lower), inward and outward (swiveling), and forward

and backward. The original driver's or passenger's seat from the vehicle manufacturer

is mounted on the seat base, providing the comfort and styling of the original seat.

Generally, the transfer seat is positioned parallel to where the wheelchair or

scooter will be secured. The transfer is then made onto the car seat and the controls

are used to rotate the seat and return it to the standard driver's or front passenger's

position. These six-way transfer seats give wheelchair users the advantage of

transferring into a more comfortable car seat for driving or riding, which is particularly

beneficial on long trips or commutes. The most commonly prescribed six-way transfer

seat is manufactured by B&D Independence, Inc.

B.

Securement Systems

Wheelchair securement systems--the means by which wheelchairs are fastened

or "secured" inside the vehicle--have been one of the most significant historical

innovations in the vehicle mobility industry. The original manual tie-downs were little

more than high-strength cargo straps with hooks to attach to the frames of wheelchairs.

This certainly enabled wheelchair users to remain in their wheelchairs while riding in a

vehicle, but did not enable them to drive a vehicle from their chairs because of the

inability to independently secure and release themselves in the driver's position. The

invention of self-retracting securements (e.g. Q-Straint and Sure-Lok) made the process

4

much faster and simpler but, again, did little to enable the operation of a vehicle while

remaining in the wheelchair.

The biggest historical advancement came in the form of an automatic, electronic

securement system by EZ Lock, which became the gold standard for automatic

securements, sometimes referred to as a "docking system." This floor-mounted docking

base, combined with a bracket mounted to bottom of the wheelchair, enabled a

wheelchair user to independently dock and undock in the driver's position. This brought

true independence to wheelchair users who could not or did not want to transfer from

their wheelchair to the driver's seat.

In recent years, Q'Straint's development of its QLK series of bases and its DiOR

(Drive-In Occupant Restraint) system has made it possible to both secure a power chair

and drive into preset lap and shoulder harnesses for those who have difficulty engaging

the standard passenger restraints in the vehicle. Again, these adaptive systems

continue to enable wheelchair users with a wider range of disabilities to independent

operate a vehicle.

C.

Hand Controls and Spinner Knobs

Clearly, on a conceptual level, there is nothing more important to adaptive driving

than hand controls. Basic mechanical hand controls have been around for many years,

but certainly there have been innovations in the style or "action" of hand controls. The

different types of actions are designed to enable those with limitations in different planes

of motion to find a style that best fits their physical needs and abilities. Likewise,

spinner knobs are designed to account for any type of grip need to enable a specific

driver to turn the wheel with one hand while operating the accelerator and brake with

the other hand (using hand controls).

The true recent innovations in these adaptive devices has been the invention of

programmable knobs (available both on hand controls and spinner knob) that control

secondary functions in the vehicle (e.g. lights, turn signals, wipers, etc.). These have

reduced the need to let go of either the spinner knob or the hand controls in order to

turn these functions on or off with the original buttons or controls. These wireless

technologies are designed to increase safety by enabling the operation of secondary

functions without taking a hand off of the primary vehicle controls.

As wireless and Bluetooth technology continues to develop, expect to see more

innovations in this area. However, many of these innovations may come from the

original vehicle manufacturers, rather than secondary manufacturers (converters), or

adaptive equipment manufacturers. As voice recognition software continues to increase

in accuracy and reliability, it is foreseeable--if not inevitable--that many of these

functions ultimately will be incorporated by vehicle manufacturers as part of voice

command options.

5

D.

Reduced Effort Steering and Braking Systems

Reduced effort steering and braking systems seek to accommodate persons with

strength deficits resulting from a broad range of causes. The systems have been

around for a long time, but they are no less important as historical innovations in

mobility. Divided into "low effort" and "zero effort" systems, they dramatically reduce the

amount of effort required to steer or to brake and, as such, empower a large group of

disabled drivers who simply lack the strength to operate them without modification.

Standard factory power steering requires approximately 35-45 ounces of effort to

operate. Depending on the specific brand, a "low effort" steering system requires only

18-26 ounces of effort. "Zero effort" systems lower the force requirements to only 5-12

ounces.

These reduced effort systems lower the strength threshold necessary to operate

a vehicle safely and significantly reduce the fatigue factor for disabled drivers. These

systems, combined with other assistive technology, broaden the universe of potential

adaptive drivers and foster independent living by persons with disabilities.

E.

High-Tech Driving Systems

High-tech driving systems are electronic adaptive vehicle control systems.

These systems utilize electronic components that interface with the original vehicle

systems to control steering, acceleration, and braking. They integrate controllers for

"secondary" vehicle functions, such as horn, wipers, turn signals, windows, and mirrors.

High-tech driving systems are customized for the unique abilities and limitations

of quadriplegic, and other disabled drivers, to enable them to safely operate a vehicle.

There are even systems that have been developed to enable a person without upper

extremity function to drive exclusively with head motion.

The industry standard is EMC's AEVIT 2.0® system, which is available for (1)

Gas/Brake & Steering, (2) Gas/Brake Only, or (3) Steering Only. There are available

AEVIT 2.0® Secondary Control Functions and DigiTone® audible switches.

Other commonly prescribed high-tech systems include the Joysteer Driving

System, and the Scott Driving System.

F.

Back-Up/Side View Cameras

We don't often think of the back-up camera as adaptive equipment or assistive

technology outside the mobility industry, but the back-up camera is unquestionably

adaptive equipment in vehicle mobility. Drivers with limited cervical and/or trunk rotation

have a far more difficult time backing up their vehicles safely. The inability to lean or

rotate (or both) creates more blind spots and makes lines of sight from the driver's

6

position problematic. The backup camera solves this problem by eliminating the need

to shift or rotate when backing the vehicle.

In 2015, Honda began offering its Odyssey minivan with both a back-up and a

right side view camera as standard equipment. Again, while these were not specifically

engineered with disabled drivers in mind, the reality is that these innovations make the

vehicle easier to operate for both able-bodied and disabled drivers alike. Moreover, the

inclusion of these assistive devices as standard equipment eliminates the need to install

(sometimes expensive) after-market equipment to perform the same functions, and

thereby lowers the overall vehicle cost for disabled drivers.

G.

GPS Navigation Systems

Similarly, turn-by-turn GPS navigation systems constitute a convenience for

some, but can be indispensable adaptive driving equipment for disabled drivers.

Diminished ability to shift and rotate reduces the functional field of vision for drivers,

rendering it more difficult to look for and see road signs and landmarks for navigational

purposes. Available turn-by-turn GPS navigations systems allow disabled drivers to

overcome the restricted functional field of vision and simply following the navigation

system's verbal instructions. As voice recognition and GPS technologies continue to

improve, these assistive technologies will continue to simplify the lives of disabled

drivers.

IV.

WHAT’S AHEAD

Predicting what lies ahead is never an easy task. Someone may rethink the

problem and come up with something entirely new and different. Who’s to say?

In the short term, secondary manufacturers are starting to offer reliable

conversions for more types of vehicles--pickup trucks, SUVs, and smaller passenger

cars. This will expand the consumer choices available to disabled drivers

However, in my opinion, the most significant future development in vehicle

mobility and adaptive driving equipment might not be a type of adaptive driving

equipment at all. It may turn out, in fact, to be autonomous vehicles, i.e. vehicles that

drive themselves without human input. So much research and development is being

done in the area of autonomous vehicles by so many major manufacturers that we can

no longer consider the concept futuristic. It is, instead, the inevitable march of

technology. An autonomous vehicle is capable of sensing its environment--roadways,

traffic controls, other vehicles, pedestrians, and fixed objects--and navigating without

any human input whatsoever.

Obviously, even autonomous vehicles will still require modification to enable

wheelchair user ingress, egress, and securement. However, the problems associated

with adaptive driving may be rendered largely irrelevant if wheelchair users do not have

to drive the vehicle at all. Already, technologies such as parking assist, blind spot

7

monitoring, and radar collision avoidance systems are commercially available through a

wide range of manufacturers. As these and more advanced autonomous vehicle

technologies evolve and are perfected, they will eliminate the need for a broad range of

currently available adaptive driving equipment. Obviously, those who can drive and still

want to drive will continue to use the other adaptive driving equipment we've

summarized.

V.

CONCLUSION

The vehicle mobility and adaptive driving equipment industries have made

numerous innovations over time. Society has advanced from a point where wheelchair

users were not independently mobile in a vehicle, to the present state of the art where a

wide range of disabilities can be accommodated through assistive technologies to

enable persons with disabilities to enjoy true independence and self-determination.

Secondary manufacturers continue to develop conversions for more and more

types of vehicles so as to more precisely fit the needs of a specific individual. Adaptive

equipment manufacturers continue to keep pace with these advancements and have

introduced innovations of their own. Perhaps ironically, traditional vehicle

manufacturers have incorporated more advanced technologies, such as back-up

cameras, voice command, and GPS navigation, as either standard equipment or readily

available optional equipment. While these have been adopted for traditional vehicle

buyers, they have had a profound effect for disabled drivers.

No one knows for sure what the future holds for vehicle mobility and adaptive

driving equipment, but one thing is certain. As advanced technologies continue to be

developed at an ever-faster pace, the spillover into the world of disabled driving will

bring amazing results for drivers who rely on assistive technologies in vehicle mobility.

The future for disabled drivers is coming faster than we think.

Dan Radacosky is one of Arizona's premier lecturers and clinical instructors in the field of vehicle mobility. He has presented to

occupational therapists, physical therapists, nurse case managers, vocational rehabilitation counselors, and other industry

professionals at seminars, clinical in-services, conferences, and trade organizations, teaching how vehicle mobility dovetails with

acute and rehabilitative clinical care and how innovations in vehicle mobility can improve the quality of life of wheelchair users. He

has also instructed at numerous wheelchair skills clinics and at support groups to build awareness and to introduce a clinical

approach to vehicle mobility. Dan is a Certified Mobility Consultant and is the General Manager at Performance Mobility in Mesa,

Arizona.

© 2015 Dan Radacosky

All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission.

8