Current controversies in prostate cancer screening

advertisement

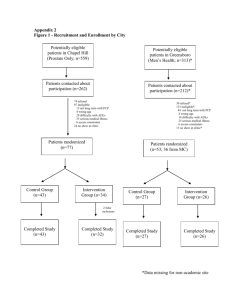

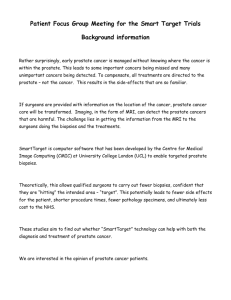

Current Controversies in Prostate Cancer Screening and Treatment Mr Stephen Lindsay Urological Surgeon Bendigo www.bendigourology.com Since the early 1990’s, Prostate Cancer has been the most commonly diagnosed cancer in Australian men (approx 20,000 new cases/year). Why the increase? • Community awareness that testing is available • Improved risk assessment tools - PSA and TRUS biopsy became widely available in the early 1990’s • Improved access to risk assessment – more GP’s and Urologists • More treatment options available, with less morbidity • Male life expectancy has increased – more men living longer It is the second most common cause of cancer death in men. Over 3000 men die of Prostate Cancer each year (4.1% of all male deaths). WHO Screening Criteria - 1968 The condition sought should be an important health problem. There should be accepted treatment for patients with recognized disease. Facilities for diagnosis and treatment should be available. There should be a recognizable latent or early symptomatic stage. There should be a suitable test or examination to be used for screening. The tests should be acceptable to the population. The natural history of the condition, including development from latent to declared disease, should be adequately understood. 8. There should be an agreed policy regarding whom to treat as patients. 9. The cost of case-finding (including diagnosis and treatment) should be economically balanced in relation to possible expenditure on medical care as a whole. 10.Case-finding should be a continuing process, and not a “once and for all” project. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. • Wilson and Jungner, “Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease” • World Health Organization 1968 WHO Screening Criteria – (Revised 2008) 1. The screening programme should respond to a recognized need. 2. The objectives of screening should be defined at the outset. 3. There should be a defined target population. 4. There should be scientific evidence of screening programme effectiveness. 5. The programme should integrate education, testing, clinical services and programme management. 6. There should be quality assurance, with mechanisms to minimize potential risks of screening. 7. The programme should ensure informed choice, confidentiality and respect for autonomy. 8. The programme should promote equity and access to screening for the entire target population. 9. Programme evaluation should be planned from the outset. 10.The overall benefits of screening should outweigh the harm. • World Health Organisation 2008 Population-based Screening • Large scale testing of an entire geographical population of apparently healthy volunteers for the presence or absence of disease eg Breastscreen (screening centres, mailed invitations) Selective Screening of at-risk populations • limited testing targeted at high risk populations eg family history, African-American Opportunistic testing (or Case Finding) • investigation of men (with or without symptoms) as part of a routine medical consultation Prostate cancer specific survival in Victoria has improved dramatically over the last 20 years. "Most men die with, rather than of, their Prostate cancer." This is misleading, particularly for men in their 50’s and 60’s. A man aged 70 has a 38% chance of dying of the cancer before 80 years of age But, a man aged 50 has a 60% chance of dying before 80 years of age. So younger men are “More likely to die of, rather than with, their Prostate cancer.” Increasing numbers of older men are surviving other diseases and living longer. There will be a dramatic increase the numbers of men diagnosed and living with Prostate cancer in the next 20 years. The Melbourne Consensus Statement on Prostate Cancer Testing (2013) Consensus statement: Older men in good health with over 10 year life expectancy should not be denied PSA testing on the basis of their age. • Men should be assessed on an individual basis, particularly as life expectancy increases. Urban vs. Rural Comparison • • Men from city and country areas in Australia have the same lifetime risk of developing Prostate Cancer Average age at diagnosis is the same at approximately 71 years but ... • Men from country areas are 2.6 x more likely to die from Prostate Cancer in the first 5 years after diagnosis than men in metropolitan areas. The Natural History of Prostate cancer can vary enormously: • slow indolent cancers with a long latent period of 10-15 years before they develop clinical disease (obstructive symptoms, metastases) and need treatment • very aggressive cancers with progression to metastatic disease within a few years despite maximal treatment The long interval of “latent disease” for less aggressive cancers gives us a large window of opportunity to diagnose while the cancer is still at a curable stage. But the life-threatening cancers we need to find and treat are the more aggressive cancers, with a shorter latent period. Active surveillance programs use this long interval of “latent disease” in patients who have less aggressive cancers with a low risk of progression. In Australia now, around 30% of newly diagnosed men with Prostate cancer are on active surveillance, with treatment with curative intent offered to those who show signs of cancer progression. The Melbourne Consensus Statement on Prostate Cancer Testing (2013) Consensus statement: For men aged 50-69, Level 1 evidence demonstrates that PSA testing reduces prostate cancer specific mortality and incidence of metastatic prostate cancer. ERSPC Trial • 1991-2003 182,160 men from 7 centres, age 50-74 years • screening reduced prostate cancer specific mortality by 21% and progression to metastatic disease by 30% (at 11 years follow-up) • To prevent one death (at 11 years follow-up) – 936 men would need to be invited to screen and 33 cancers would need to be diagnosed. Goteborg Subgroup of ERSPC • randomised population-based trial (20,000 men screened from age 50 years) showed reduction in prostate cancer mortality by 44% at 14 years follow-up • To prevent one death (at 14 years follow-up) – 293 men would need to be invited to screen and 12 cancers would need to be treated The Melbourne Consensus Statement on Prostate Cancer Testing (2013) Consensus statement: PSA testing should not be considered on its own, but rather as a part of a multivariable approach to early prostate cancer detection. • • • • Age specific PSA (reduces false negatives in young men, false positives in older men) PSA Velocity (or doubling time) Prostate Health Index (phi) – mathematical formula combines total PSA, free PSA and (-2) pro-PSA (a PSA isoform) Urinary PCA3, other new biomarkers Online tools • ERSPC risk calculator • Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial risk calculator The Melbourne Consensus Statement on Prostate Cancer Testing (2013) Consensus statement: Baseline PSA testing for men in their 40s is useful for predicting the future risk of prostate cancer. An assessment at 40 years allows risk stratification before BPH-related PSA elevation occurs. • Men with PSA levels below the median are less likely to develop Prostate cancer and need not be tested as often. • Men with PSA levels above the median are at increased risk and should be tested more often. Age Specific Reference Ranges, Median PSA Digital Rectal Examination (DRE) Increased firmness, hardness, nodularity, irregularity, asymmetry, cragginess Sensitivity of DRE in detecting Prostate cancer • GP 26.5% • Specialist Urologist 61.8% One in four men with a normal PSA have an abnormal DRE due to Prostate cancer Health professionals need to be trained to do DRE properly if they are to competently assess Prostate cancer risk Who Should be referred to a Urologist? • • • • Age-specific PSA Elevated DRE Abnormal or Both PSA Velocity • PSA rising at greater than 0.5ng/ml/year is suspicious for cancer • PSA doubling time • <2 years – high risk • <5 years – intermediate risk • > 5 years low risk • Free/Total PSA Ratio – can help to distinguish non-cancer from cancer for PSA in the range 2-10ng/ml. A FT ratio <10% is suspicious for cancer (a higher level does not exclude cancer) 50 year old man – Prostate Cancer Risk Assessment PSA - 5.4 ng/ml (normal <3.5 ng/ml) DRE - firm prostatic nodule on the right side, with no extension into the lateral sulcus or seminal vesicle (T2a) FHx - No PCPT Risk Calculator Risk of high grade CaP Risk of low grade CaP 5% 18% Likelihood that the biopsy is negative 77% 50 year old man – Prostate Cancer Risk Assessment TRUS Biopsy • Hypoechoic area right side corresponding to nodule • 5/14 cores involved (2-5mm right side) • Gleason score 3+3=6 Radiological Staging • CT Abdomen/Pelvis • Bone Scan – N0 – M0 What type of Prostate Biopsy? Trans-Rectal vs Trans-Perineal Ultrasound-guided Biopsy of the Prostate Trans-Rectal Trans-Perineal • 14-16 cores • Inadequate sampling of anterior prostate • 20+ areas sampled, multiple cores • mp-MRI fusion • Sepsis 2-3% (ESBL) • Retention <1% • Bleeding mild • Sepsis almost 0% • Retention 2-5% • Bleeding increased, pelvic haematoma • Erectile dysfunction • Peri-prostatic scarring • Anaesthetic Risk • Dramatically increased cost Low Risk Intermediate Risk High Risk T1 – T2b Gleason < 7 PSA < 10 T2c – T3a Gleason 7 PSA 10 - 20 T3b – T4 Gleason > 7 PSA > 20 D’Amico 1998 Multi-parametric MRI for Prostate Cancer diagnosis Multiparametric-MRI (mp-MRI) for Risk Stratification mp-MRI combines diffusion-weighted, dynamic contrastenhanced sequences (or MR Spectroscopy) with conventional T2 weighted sequences. This shows anatomy, tissue density and blood supply. Potential Advantages • Only detects cancers 7mm or larger with Gleason grade 4 or 5 • It has the potential to offer improved detection and risk stratification of intermediate/high risk cancers. • mp-MRI targeted biopsies may lead to • fewer biopsies, with fewer cores at each biopsy • reduced detection of clinically insignificant disease • better representation of disease burden "cancer core length, Gleason score" Multi-parametric MRI for Prostate Cancer diagnosis Multiparametric MRI (mp-MRI) for Risk Stratification BUT…. • Mp-MRI is highly technique and operator dependent, requiring two dedicated Uro-Radiologists for each report. The technique and exact use is evolving and still in its infancy. • Mp-MRI should not be considered as a definitive study on its own but rather one part of a comprehensive assessment. Biopsy must still be performed to confirm the presence of tumour and to assess Gleason score We need prospective randomised trials to assess the role of mp-MRI in Prostate cancer screening. Mp-MRI is not currently reimbursed by Medicare or private health funds for prostate imaging. Patient Factors • • • • What is his life expectancy? Will he benefit from treatment? Is he prepared to accept active surveillance? What Quality of Life is he prepared to sacrifice to be cured of his cancer? Cancer Factors • Is this Prostate cancer life threatening or likely to cause significant morbidity? • Is it curable with the treatment? Available Treatments • What are the available treatments options for that patient and that cancer? • What are the risks and benefits of each option for this man? Treatment options for Localised Prostate cancer Active Surveillance Radical Prostatectomy • Open Retropubic, Perineal , Laparoscopic, Robotically-Assisted RP Radiotherapy • Intensity Modulated External Beam (IMRT) • +/- Neo-adjuvant LHRH to downsize • +/- Adjuvant LHRH for 2-3 years (survival advantage) • Brachytherapy • Low Dose Rate Seeds (I125) • High Dose Rate + EBRT Hormone Therapy • LHRH (eg Goserelin, Leuprorelin) • Antiandrogen (steroidal or non-steroidal) The Melbourne Consensus Statement on Prostate Cancer Testing (2013) Consensus statement: Prostate cancer diagnosis must be uncoupled from prostate cancer intervention. • Active surveillance protocols have been developed and shown to be a safe option for many men with low volume, low risk prostate cancer. This does not address the issue of over-diagnosis, but does reduce excessive intervention. Active Surveillance/Watchful waiting Active surveillance is a management strategy for a man who would benefit from treatment but where the cancer is too small to recommend active treatment. • The cancer is closely monitored for change in PSA, size or aggressiveness (which requires repeat biopsy at defined intervals). • If the cancer is found to progress, then definitive treatment with surgery or radiotherapy is offered. • Currently around 40% of men newly diagnosed with Prostate cancer in Australia are commenced on Active Surveillance. Watchful waiting is the no treatment option for elderly men who are not likely to benefit from definitive treatment. • Observation of PSA and symptoms, no repeat biopsy. Intensity Modulated Radiotherapy (IMRT) • 78Gy in 39 fractions • 5 treatments/wk = 8 weeks • Small gold markers or fiducial seeds are inserted into the prostate (by TRUS) to improve targeting. • External Beam Radiotherapy can be accurately focused onto the Prostate, minimising radiation toxicity to the adjacent bladder and bowel • Neoadjuvant Hormone therapy is often given to patients with intermediate to high risk cancers prior to commencing Radiotherapy Brachytherapy Seed Implantation (Low Dose Rate) Radioactive I125 seeds are implanted into the prostate by a Urologist and Radiation Oncologist. The I125 seeds deliver a precise, high dose of photons to a small localised are around the seed. The I125 seed’s radioactivity decays with a T½ of 60 days. Patients are radioactive and radiation safety precautions must be taken. Brachytherapy Seed Implantation (Low Dose Rate) - Technique A TRUS volume study is performed to measure prostate size, 3D shape and the position of bladder, urethra and rectum. A dose plan is determined. Implantation Procedure • TRUS is used to guide seed placement following the dose plan. • From 60 to 120 I125 seeds are inserted • The procedure takes approx 45 minutes and the patient stays in hospital overnight. Radical Prostatectomy - History 1906 – first Radical Prostatectomy at Johns Hopkins University Early 1980’s - Dr Patrick Walsh et al published anatomical studies on pelvic venous and nerve anatomy. The Walsh Radical Prostatectomy (or open Radical Prostatectomy) revolutionised the surgical technique and dramatically reduced blood loss and surgical morbidity. 1990’s – now - Subsequent refinements in technique, including "nerve sparing" Radical Prostatectomy followed. Open Radical Prostatectomy - Technique • • • • • • • Retropubic or Perineal approach Pelvic LND Dorsal Venous complex ligated and divided Nerve sparing prostate dissection Urethra transected, prostate mobilised Bladder neck divided Vesico-urethral Anastamosis Post-operative complications - urinary incontinence sexual dysfunction 5-10% 40-85% The da Vinci™ Robot-assisted Radical Prostatectomy (RARP) - Technique • The console surgeon uses 3D HD images to drive computer simulation to manipulate the robotic arms • The table-side assistant inserts the laparoscope and 4-5 laparoscopic ports for the robotic arms • “Endowrist” instruments provide precise control with increased range of motion and improved dexterity • The prostate is removed through a large port • RARP takes 3-6 hours • Hospital stay 1-3 days, patient home with urethral catheter for 2-3 weeks Controversy - Robotic-Assisted Prostatectomy a “pseudo-innovation—a technology that increases costs without improving patients’ health” a “fake innovation” Dr Ezekiel Emanuel Medical Oncologist and former White House Advisor New York Times May 2012 Urologists worldwide have embraced RARP with enthusiasm, and it is now well established as a leading treatment for localised Prostate cancer. BUT how does it really compare with open Radical Prostatectomy? • operative bleeding (transfusion rates), longer operation time, earlier discharge and possibly earlier return to work. • higher cost (consumables, theatre time, doctors fees) • achieves equivalent cancer control (surgeon learning curve) • claimed to improve recovery of urinary continence and erectile function but this is not yet proven The da Vinci Robotic-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy has highlighted the concerns surrounding the costs of Healthcare and particularly cancer treatment in the United States. In the USA, RARP adds • • $2,200 US to the cost of a Radical Prostatectomy (increased consumable costs and operating room time) additional $400 to $4,800 US per case in capital costs and maintenance of the da Vinci Robot Health Administrators are increasingly analysing the cost/benefit of new therapies to ensure that they are cost effective and improve QALY’s. Why has RARP polarised the debate in health care delivery? There is an impending crisis affecting the diagnosis and management of prostate cancer in most Western countries. • • • • • aging and expanding population new genetic-based screening tests more sophisticated and expensive imaging tools (eg MRI) improved treatment technologies new pharmaceutical developments Many factors have conspired to drive health expenditures for cancer, especially Prostate cancer, to unsustainable levels. We have reached a point where the current paradigm of health care delivery is changing. Medical Education and Research has traditionally focused on technical skills and clinical decision making. Doctors have not had to justify the costs of treatments that we recommend. Governments and organisations responsible for paying for health care are now demanding evidence that therapies we promote truly provide value to large numbers of patients. Unfortunately, we don’t have wellconstructed randomized trials that demonstrate the cost/benefit of many of the things we do. Lifetime Risk • “Microscopic” Prostate cancer • - 30% many of these cancers will be low risk. • “Clinical” Prostate cancer - 10% • Dying of Prostate cancer - 4.1% The Challenge “For a patient with Prostate cancer, if treatment for cure is necessary, is it possible? If possible, is it necessary?” Whitmore 1970’s or to put it another way, “How do we best find men with significant disease who are going to benefit from diagnosis and treatment”. "Treatment or no treatment decisions can be made once a cancer is found, but not knowing about it in the first place surely burns bridges" Dr Joseph Smith, J Urology Editorial 2009