Rwanda UNDAF 2008-2012 Evaluation

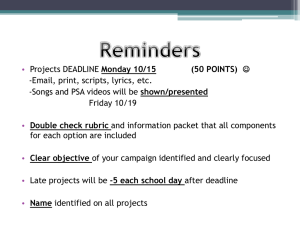

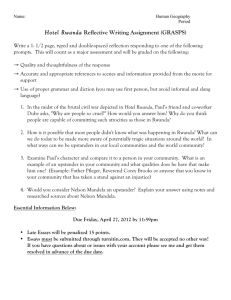

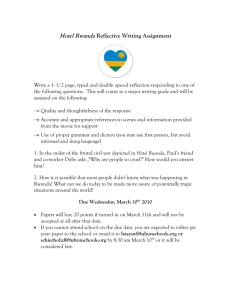

advertisement