Presentation 4

advertisement

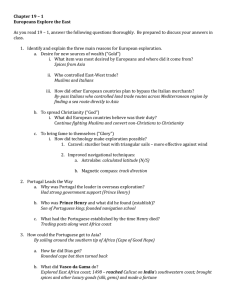

The Impact of Gentrification in Toronto’s “Little Portugal” - Canada Carlos Teixeira University of British Columbia – Okanagan Campus and Metropolis Canada carlos.Teixeira@ubc.ca This paper explores issues related to neighbourhood change in Toronto’s “Little Portugal”, and addresses the following questions: • What are the main positive and negative impacts of gentrification on “Little Portugal”? • Does gentrification mean the displacement of lower income households, including the ageing first generation Portuguese, or are there viable strategies of resistance? Introduction • Toronto, the largest and most multicultural city of Canada, has been for the last five decades the major “port of entry” for Portuguese immigrants arriving in Canada • Portuguese immigration to Toronto began in the early 1950s, and attained its peak in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In 2001, according to the Canadian Census, 357,690 Portuguese were living in Canada – largest concentration of Portuguese (171,545) in the country (Statistics Canada, 2001) Introduction • Toronto’s “Little Portugal” is located in the St. Christopher House catchment area of west central Toronto • This neighbourhood today contains most of the community’s social, cultural, commercial and religious institutions • as this concentration might suggest, the Portuguese have also been among the most segregated groups in Toronto (Murdie and Teixeira, 2006). Introduction • Evidence from census data reveals that the Portuguese community in Toronto has expanded in two areas of new settlement in recent years 1. Northwest of “Little Portugal” along the traditional “immigrant corridor” where the Portuguese are replacing the Italians 2. The western suburbs and, in particular, in the cities of Mississauga and Brampton. Introduction • “Little Portugal” is today a neighbourhood in transition. This transition has resulted from three major changes: 1. The movement of a large number of Portuguese to the suburbs 2. An in-movement of immigrants and refugees from the Portuguese diaspora (Brazil and Portugal’s former African colonies) 3. And in-movement of an increasing number of the urban professional class who see an opportunity to obtain relatively low cost housing with potential for renovation in close proximity to the city’s downtown core. Introduction • These characteristics serve to explain why “Little Portugal” has today become an area of emerging gentrification – Residential and commercial gentrification – “invasion/succession” of different populations (Portuguese and non-Portuguese speaking immigrants, African refugees and white middle-class Canadians) • Has implications for the “life-cycle” of “Little Portugal” Gentrification Gentrification has been defined as “the loss of affordable older inner-city housing through their renovation and upgrade by middle- and upper-income households” (Meligrana and Skaburskis, 2005, p. 1571) • In the Canadian context, most of the opportunities for gentrification – and its greatest potential to displace low-income households – are found within low-income inner city neighbourhoods (often ethnic/immigrant neighbourhoods) with a high proportion of older dwellings (Meligrana and Skaburskis, 2005, p. 1571) Gentrification • In the Canadian context very little is known about the costs of gentrification upon ethnic neighbourhoods, and much less regarding its impact upon one segment of these neighbourhoods’ populations – immigrant seniors Research Questions 1. What are the main positive and negative impacts of gentrification on “Little Portugal”? 2. Does gentrification mean the displacement of lower income households, including the ageing first generation Portuguese, or are there viable strategies of resistance? Table 1 Data Collection (July and August 2006) Informal interviews: Portuguese (N=20) Non-Portuguese (“Canadians”) (N=20) Total participants/Informal interviews – (N=40) Focus groups: Portuguese speaking immigrants (N=3) Mixed group (Portuguese speaking immigrants and Non-Portuguese) (N=2) Non-Portuguese (“Canadians”) (N=1) Total participants in the focus groups – N=42 (N=27 Portuguese speaking* and N=15 Non-Portuguese/”Canadians”). *N=27 Portuguese speaking includes N=13 Portuguese and N=14 Portuguese speaking immigrants from Brazil (9), Angola (2), Mozambique (2) and Cape Verde Islands (1)) ** Four out of the six focus groups took place at the St. Christopher House, one at ABRIGO and one at BIA-Dundas St. West. – Toronto. ________________________________________________________________________ Source: Informal Interviews and Focus Groups (Summer 2006) Table 2 Negative Impacts of Gentrification ________________________________________________________________________ Portuguese (N=31*) ________________________________________________________________________ Loss of affordable housing 77.4% Displacement through rent/ price increases 58.6 Unsustainable speculative property price increases 48.4 Commercial/industrial displacement 38.7 Community resentment and conflict 38.7 Increased cost and changes to local services 32.3 Homelessness 29.0 Greater draw on local spending through lobbying by middle-class groups 29.0 Loss of social diversity (from socially disparate to affluent ghettos) 25.8 Secondary psychological costs of displacement 22.5 Under-occupancy and population loss to gentrified areas 22.5 Increased crime 19.4 ________________________________________________________________________ Adapted from Atkinson (2004) *Missing Cases - 2 Source: Informal Interviews and Focus Groups (Summer 2006) Table 3 Positive Impacts of Gentrification ________________________________________________________________________ Portuguese (N=31*) ________________________________________________________________________ Increased property values 64.5% Increased social mi x 58.1 Stabili zation of decli ning areas 48.4 Encourage ment and increased viabili ty of further development 45.2 Reduced vacancy rates 32.3 Increased local fiscal revenues 32.3 Decreased crim e 25.8 Reduction of suburban sprawl 19.4 ________________________________________________________________________ Adapted from Atkinson (2004) *Missing Cases - 2 Source: Informal Interviews and Focus Groups (Summ er 2006) Table 10.1: Total population and Portuguese population (single ethnic origin): Portugal Village, West Central Toronto, Mississauga and Toronto CMA, 1971, 1981, 1991 and 2001 Area 1971 1981 1991 2001 Total Population 44,590 35,140 33,050 30,940 Portuguese 12,285 19,655 15,945 11,220 % Portuguese 27.6 55.9 48.2 36.7 Total Population 124,355 103,110 106,276 108,190 Portuguese 18,235 31,645 27,125 19,660 % Portuguese 14.7 30.7 25.5 18.2 Total Population 162,920 299,115 471,013 629,875 Portuguese 1,415 8,655 21,175 25,280 % Portuguese .009 2.9 4.5 4.0 Total Population 2,628,125 2,998,947 3,893,046 4,647,955 Portuguese 39,550 127,635 124,330 129,280 % Portuguese 1.5 4.3 3.2 2.8 Portuguese Portugal Village/ Portuguese Toronto CMA 31.1% 16.4% 12.8% 8.7% Portuguese West Central Toronto/ Portuguese Toronto CMA 46.1% 24.8% 21.8% 15.2% Portuguese Mississauga/Portuguese Toronto CMA 3.6% 6.8% 17.0% 19.6% Portugal Village West Central Toronto Mississauga Toronto CMA Variable Portuguese (West Central Toronto) Portuguese (Mississauga) Total Population (Toronto CMA) 69.5 59.0 45.2 1961-1970 (%) 25.8 33.0 12.4 1971-1980 (%) 37.8 38.4 16.9 1981-1990 (%) 22.1 15.2 20.8 Age and Household Structure Less than 15 Years (%) 12.0 16.4 19.8 15-24 Years (%) 15.6 15.9 13.1 25-44 Years (%) 29.2 34.4 33.3 45-64 Years (%) 26.7 23.9 23.0 65 Years and Over (%) 16.5 9.4 10.8 One Family Household (%) 72.8 84.1 69.8 Less Than Grade 9 (%) 47.1 26.7 9.2 Grades 9 to 13 (%) 27.8 37.0 27.0 Some College/University (%) 20.5 30.2 38.9 4.6 6.0 24.9 Management (%) 5.6 9.1 12.6 Professionals (Skill Level A) (%) 5.8 6.5 18.5 Supervisors etc. (Skill Level B) (%) 31.1 30.8 26.1 Clerical Workers etc. (Skill Level C) (%) 28.6 34.9 31.6 Sales & Service, Other Manual (Skill Level D) 28.7 18.1 11.3 $59,995 $80,210 $76,454 Immigrant Population Table 10.2: Selected characteristics of a) The Portuguese population: West Central Toronto and Mississauga, 2001 and b) Total population, Toronto CMA Born Outside Canada (%) Educational Achievement University Degree (%) Occupation Income Average Household Income Seniors on the Move: Why are First Generation Portuguese Moving Out? • Who moves out of “Little Portugal”? – Respondents identified three main groups leaving the area for reasons both voluntary and forced 1) Portuguese in their 40s or 50s, who are currently homeowners in “Little Portugal” 2) Well-off Portuguese seniors, with their house mortgages paid, who move in order to join their children already established in the suburbs 3) Portuguese seniors who are retired and on fixed incomes Seniors on the Move: Why are First Generation Portuguese Moving Out? • Opinions in the Portuguese community are quite divided vis-à-vis the pros and cons of Portuguese seniors moving from “Little Portugal” to the suburbs “This old generation spent a lot of years in Little Portugal and they were used to do almost everything in Portuguese [businesses, services…]. In the suburbs is different….they will be more isolated. Some return back after a few years in the suburbs.” Seniors on the Move: Why are First Generation Portuguese Moving Out? • In other cases, they maintain a close contact with the Portuguese neighbourhood of “Little Portugal” via frequent visits to shop in the Portuguese businesses and/or participating in the social, cultural and/or religious life of the Portuguese community “I have seen a lot of my clients living far away from “Little Portugal”…in the suburbs. However, they return to do their shopping in “Little Portugal”. My Bank [Portuguese owned] decided to open on Saturdays because we have clients that come from Mississauga, Brampton Kitchener, Cambridge….to do their banking with us.…coming/visiting on weekends our “Little Portugal” is like going home….” The Seniors Who Stay: Why they Remain? • Most of the Portuguese who decided to stay in “Little Portugal” are first generation, born in Portugal, “blue collar” workers with low levels of education and little knowledge of the English language • This group is the least assimilated of all Portuguese, and is also a population that is ageing fast with an important number of them already retired. The Seniors Who Stay: Why they Remain? • This group seems to be resisting gentrification. Regarding those Portuguese who resist gentrification to stay in “Little Portugal” respondents noted: “The majority of those that stay here are first generation Portuguese…the ones who arrived in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s…the ones that were able to renovate their houses to accommodate their housing needs…and some due to lack of mobility – both social and physical decided to stay…” “A lot of senior Portuguese are managing a house at the expense of their health…what a price! But this shows to me how important that is for them.” The Seniors Who Stay: Why they Remain? • Key to this resistance to gentrification is the importance of proximity to “Little Portugal” – mainly to Portuguese services, businesses, cultural and religious institutions – as a source of security for this particular group of Portuguese. The Seniors’ Perspective: Benefits of Gentrification • For almost two thirds (64.5%) of the Portuguese respondents, the “increased property values” as well as the “increased social mix” of peoples (58.1%) into “Little Portugal” represent by far the two most positive impacts of gentrification in the neighbourhood The Seniors’ Perspective: Benefits of Gentrification • However, the increased property values in the neighbourhood represent a “mixed blessing” for with increased property prices in “Little Portugal” also come increases in property taxes. This aspect of the gentrification phenomenon particularly affects Portuguese seniors, who are often retired and living on fixed incomes. The Seniors’ Perspective: The Downside of Gentrification • For Portuguese respondents the “loss of affordable housing” (77.4%) in “Little Portugal” is the most important negative impact of gentrification in the area, followed by “displacement through rent/price increases” (58.6%) and “unsustainable speculative property price increases” (48.4%) The Seniors’ Perspective: The Downside of Gentrification • According to the Portuguese key informants, Portuguese seniors are perhaps the segment of the Portuguese population most impacted by gentrification, followed by low income renters • As some respondents noted, the Portuguese have been known for being a resourceful community where through the help of internal “informal” ethnic networks of contacts (friends and relatives) they have been able to considerably improve their housing conditions/quality through renovations. However, some noted that things have changed for Portuguese seniors: Portuguese Seniors - Renting Part of the House as a “Survival Strategy” • Some Portuguese senior homeowners are already facing serious challenges to keep their houses. In the face of drastic increases in property taxes and maintenance/utilities costs as a consequence of gentrification, they are coping by renting parts of their houses • This strategy seems to work for most of the Portuguese seniors, particularly the ones more in need of cash, who will rent part of their dwellings in a very “informal” (verbal) way where receipts are not necessary (avoiding taxes). Accommodating the Housing Needs and Preferences of Portuguese Seniors: Housing Policy Implications • A major source of preoccupation in “Little Portugal” today is the ageing of the community. There is agreement among our respondents that more needs to be done in order to accommodate the housing needs/preferences of our Portuguese seniors: Accommodating the Housing Needs and Preferences of Portuguese Seniors: Housing Policy Implications “The solution for an aging population is more incentives for them to take care of their own homes…aging in place is a good way to go. Also there is an urgent need in our community for more housing for seniors…Some of them do not need any type of assistance so far, neither physically or financially...the only problem they have is that they can not take care of their homes anymore and the expenses to keep up a house today are very high. What they need is a place where they can spent the rest of their lives in peace….feeling at home [‘ambiente Portugues’]…It’s a group of citizens that is growing in a scary kind of way.” Accommodating the Housing Needs and Preferences of Portuguese Seniors: Housing Policy Implications “There is a great need for seniors housing like Terra Nova in here. Lots of people want to go there. People come from Orangeville to come and live here … now that they are seniors they want to have what they are used to around them…I find the Portuguese speaking community wants more buildings like that where there’s high concentration – not necessarily all of them, but where it’s close to “Little Portugal” …because to most of the Portuguese going to the nursing home is the last resort…” [FG]. Accommodating the Housing Needs and Preferences of Portuguese Seniors: Housing Policy Implications “I am a social worker…I see the problems they face. Aging in place is the first choice for the majority of Portuguese seniors and they will do their best to stay in their homes. We should also follow the lead of other immigrant groups like the Italians, the Chinese…in Toronto that built specific seniors housing that caters to their cultural needs and preferences – linguistic, food…I mean ethnic oriented senior homes. After 50 years in this country we could have done better…the Portuguese community need to put their mouth where the money is…building and catering specifically to the needs of the Portuguese community seniors…from a business point of view they would make a lot of money. At my knowledge the demand is there but the need has not been filled.” Conclusion • In general, all of the Portuguese respondents in this study agreed that “Little Portugal” is a neighbourhood in transition. • There was also a general consensus that the population most impacted by the forces of gentrification that are now re-shaping the residential areas of downtown Toronto – including “Little Portugal” – are the aging first generation Portuguese immigrants, now seniors, who originally bought and renovated their homes decades earlier in a more inexpensive housing market. Conclusion • As the responses indicate, there is widespread recognition in Toronto’s Portuguese community today that many Portuguese seniors are confronted by the dilemma of being “land rich and cash poor” • Gentrifiers, mostly urban professionals, are seeking to move into downtown areas such as “Little Portugal” and this demand is having a significant impact upon housing prices in the area. While respondents generally regard this as a good thing, they also note that for Portuguese seniors this increase in property values is a mixed blessing, for it is accompanied by increasing property taxes and maintenance costs which they – often retired and living on fixed incomes – are not able to support. Conclusion • First generation immigrants concentrated together in “Little Portugal” where they built an institutionally complete community with businesses and services providing them with everything that they need to live in the Portuguese language and in a Portuguese cultural “way”… are understandably resistant to the idea of dispersing to the suburbs where housing costs are cheaper, but where they would be missing the language, culture and friendships that they enjoyed in “Little Portugal”. Conclusion • There are no easy solutions – at either the policymaking level or the community level – for the housing challenges facing Portuguese seniors who wish to keep their community alive, but who are confronted by the economic realities of gentrification, including higher property taxes Conclusion • Some respondents have suggested government providing more information and supports to members of this group on the possibility of entering the formal housing rental market. Many members of this group subdivided parts of their homes decades earlier, after they initially purchased the houses, in order to take in renters so as to quickly pay off their mortgages. Were Portuguese seniors to resort to this strategy again, with their properties now in a highly desirable location in the city of Toronto, they would go a long way towards not only easing the cost dilemmas of this group but also to providing much needed affordable housing for Toronto’s constrained rental market Conclusion • However, while this might resolve the dilemma’s facing Portuguese seniors from gentrification in the short term, in the long term this group – and “Little Portugal” – are confronted by the realities of an aging population. Some of the respondents cited this as an issue of grave concern, and one requiring state and community intervention: Conclusion • “We are ageing as a community….we will have more and more Portuguese seniors here. We will see a bipolarization …and we have not worked hard enough with the other Portuguese speaking communities living in and around “Little Portugal”. We have a lot to do to break down the isolation that separates us …It’s urgent .we need more seniors’ housing in our community….I am pessimistic…I get the feeling that we missed the “boat” already. We are one of the few communities among the largest communities in Toronto that didn’t invest enough or at all in seniors’ housing…a disaster. The major challenge now is how to accommodate our seniors in terms of housing in a cultural space where they feel at home.” Conclusion • From this perspective, while Portuguese seniors and “Little Portugal” may survive the forces of gentrification, in time this group and the community will be confronted by serious housing challenges of an aging population that may, in conjunction with gentrification, ultimately mean the end of “Little Portugal” as we know it today. Thus, while the question of the impact of gentrification upon immigrant groups, and particularly seniors, has received little attention from scholars and policymakers to date, it is clear from this case study that this issue will demand more detailed attention in future as Canada’s “baby boom” and first generation immigrant populations age and, in the process, transform Canada’s residential urban and suburban housing markets. References Atkinson, R. (2004). The Evidence on the Impact of Gentrification: New Lessons for the Urban Renaissance. European Journal of Housing Policy, 4: 107-131. Caulfield, J. (1994). City Form and Everyday Life: Toronto’s Gentrification and Critical Social Practice. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Ley, D. (1996). The New Middle Class and the Remaking of the Central City. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Meligrana, J. and A. Skaburskis (2005). Extent, Location and Profiles of Continuing Gentrification in Canadian Metropolitan Areas, 1981-2001. Urban Studies, 42: 1569-1592. Murdie, R. A. and C. Teixeira (2006). Urban Social Space. In Canadian Cities in Transition: Local Through Global Perspectives, ed. T. Bunting and P. Filion, 154-170. Toronto: Oxford University Press. Qadeer, M. (2003). Ethnic Segregation in a Multicultural City: The Case of Toronto, Canada. CERIS Working Paper Series, no. 28, Joint Centre of Excellence for Research on Immigration and Settlement, Toronto. Teixeira, C. (2006). Residential Segregation and Ethnic Economies in a Multicultural City: The Little Portugal of Toronto. In Landscapes of the Ethnic Economy, ed. D. H. Kaplan and W. Li, 49-65. New York: Rowman & Littlefield. Slater, T. (2004). North American Gentrification? Revanchist and Emancipatory Perspectives Explored. Environment and Planning A, 36: 1191-1213.