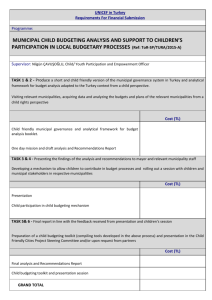

GEOG 442: URBAN LAND ASSESSMENT -- Day 5

advertisement

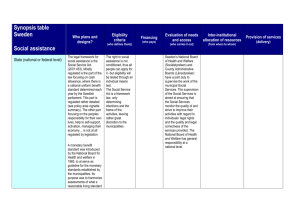

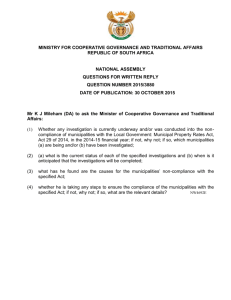

GEOG 442: URBAN LAND ASSESSMENT -- Day 5 Housekeeping Items Mark was unable to provide an example of the matrix filled in; so we will have to decide whether to proceed to fill it in on our own, use the SEED model (simplified), or a combination. I'd like to spend part of the class on our project, and part reviewing the first part of Leung. Any announcements? Context for Leung: Urban centres in BC and elsewhere in the world are undergoing rapid change. The population of Nanaimo grew by 21.4% between 1991 and 2001, and 9.3% from 20012006. As in many cities, some of this was accommodated in “greenfield” sites and some through redevelopment of existing urban areas. Context (cont’d) In contrast with the ‘60s and ‘70s, when the federal and provincial governments played more of a development role, nearly all of this is occurring through private, large-scale development companies, with municipalities and regional districts attempting to direct development in such a way as to protect what they perceive to be the public interest and to improve urban amenities. At the same time, developers and municipalities must deal with adjacent landowners and citizens’ groups who often resist land use change if it is perceived that it will have a negative effect on their property values and/or quality of life. 3 Urban Land Assessment -(Chapter 1) of Leung Urban land assessment involves a suite of tools and methods employed by the major players in the urban land development process. The methods chosen will depend on the values that are driving the assessment process. The methods, while often rigorous, are not value-neutral. Moreover, developers and municipalities are also increasingly be encouraged to approach their activities from a sustainability perspective, which adds a further layer of complexity. 4 To understand land assessment, we need to understand how people value land: as commodity or investment as resource or for its functional value as environment or amenity as ecosystem as home or homeland (heritage/ sense of place) and as bioregion, or from a sustainability perspective. 5 The role played by each of these can be seen in the history of Nanaimo: as commodity or investment (land speculation, shopping mall development, suburban tract housing, status value of certain properties and locations) as resource or for its functional value (First Nations food gathering sites, the coal resources that occasioned the first European and Asian settlement, protection of farmland in the ALR) as environment or amenity (views, access to water, favoured neighbourhoods, recreational corridors, public beaches) as ecosystem (protection of critical habitat, including riparian) as home or homeland (downtown revitalization efforts, protection of heritage artefacts, First Nations treaty process) as bioregion, or from a sustainability perspective (Regional District of Nanaimo, Georgia Basin Ecosystem Initiative). 6 Overview of Tools Appropriate to Each Concept LAND USE CONCEPT ASSESSMENT TECHNIQUES •commodity/ investment - market analysis (residential, retail, office, industrial), project pro formas • resource/ functionality - population projection and estimation, land supply inventory, land capability/ suitability analyses (e.g., sieve mapping), carrying capacity analyses, geotechnical analyses, housing needs studies, transportation demand studies, economic- base analysis, traffic impact studies, retail impact studies, fiscal impact assessment • environment/ amenity - open space analysis, carrying capacity analysis, visual preference surveys, view corridor analysis, social impact assessment • ecosystem - carrying capacity analysis, population counts, habitat assessment, ecological transects, contaminant sampling, environmental impact assessment, Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) • home/ homeland/ heritage - heritage inventories, new urbanist transects, cultural landscape surveys, resident quality of life surveys, aboriginal mapping, social impact assessment • bioregion/ sustainability - multiple accounts analysis, life cycle assessment/ full cost pricing, bioregional mapping 7 The Three-Legged Stool of Land Use Change Management: Balancing the Often Conflicting Pulls 8 The Caper’s Block in Kitsilano, Vancouver: An Example Of One Development That Does A Pretty Good Job 9 From ‘Placeless’ Planning to Place-Based Planning For most of the last century, we planned our cities around maximizing profit, maximizing efficiency, maximizing convenience for the automobile, or maximizing the prestige of various elites. We did not plan for sustainability or for the integrity of our places. The result was a loss of a sense of place. To begin to plan as if places matter, we need to understand what places are. 10 11 Key Points from Leung The PPS chart may have some relevance for our project. Certainly much of the campus has been developed without much reference to sense of place; it is quite 'functionalistic' in nature. Leung makes a number of observations: the health consideration in planning has been broadened to include mental and emotional well-being pedestrian safety and amenity, previously ignored, has become much more important and streets are being seen as much more than mere channels for traffic. 12 Key Points from Leung finding the right amount of density and compactness that avoids overcrowding, while promoting efficiency & easy access to things, has become a consideration considering the value of “brownfield” vs. “greenfield” development has become an issue increasing attention is being given as to how to balance the needs, rights, and interests of potentially conflicting groups within society. 13 Further Points planners and city councils must increasingly pay attention to environmental considerations, and are even beginning to address climate change issues (e.g. PCP) and ‘peak oil’ now that cheap fossil fuel is going the way of the dinosaur, what implications does this have for our cities? (energy consumption is directly related to land use patterns; we use 4 times as much for transportation as in Europe). 14 Further Points some municipalities are trying to ensure that there is adequate land for more affordable housing protection of public morals is sometimes seen as an issue (e.g. casinos) more municipalities are seeing development as a cash cow and/or as a means to attract investment there is also the issue of what to do with surplus government properties. 15 Players in the Land Use Game In B.C., municipalities and regional districts are the key land use planning agencies, with some roles performed by the provincial government. The municipal role is not just performed by planning departments, but also by engineering departments (roads and infrastructure), transit departments, parks departments, and others. Not all are equally wellresourced, nor are they necessarily on “the same page.” 16 B.C. Planning Law Municipalities, which do the bulk of the land use planning in Canada – at least insofar as it affects the built environment – have no constitutional authority. As one wag put it, in our antiquated 1867 Constitution (when the country was overwhelmingly rural), municipalities factored in somewhere between dogcatchers and insane asylums. They are strictly “creatures” of the provinces which can abolish them, amalgamate them, and transform them at will, while creating the legislative frameworks under which they must operate. These frameworks change from time to time. Currently, the principal law in BC is the Local Government Act. 17 Municipal Authority (cont’d) Thus, all authority exercised by municipalities, regional districts, and the Islands Trust, is delegated authority. Provincial legislation offers an interesting window on what the social priorities of the day are. One of the first powers granted to municipalities in B.C. in 1899 was the power to regulate laundries, mostly Chinese-owned (was this motivated by racism?). This was followed, in 1908, by an amendment to allow municipalities to regulate “dancehalls,” skating-rinks, and other places of amusement. 18 Municipal Authority (cont’d) In that same year, municipalities gained the right to regulate noxious industries and land uses that might reduce residential or commercial property values. A few years later, a law was passed that enabled local governments to zone areas for exclusively residential use. Point Grey, near what is today UBC, which was then separate from Vancouver, was the first municipality in BC, and one of the first in Canada, to pass a comprehensive zoning bylaw in 1922. 19 Municipal Authority (cont’d) B.C. passed its first comprehensive zoning legislation in 1925. Municipalities are governed by various versions of the Local Government Act, which is revised every few years. In January 2004, the Liberal government passed a new law, the Community Charter (January 2004), which gives municipalities expanded powers. However, it doesn’t affect land use planning much. In addition, Vancouver has had its own Charter for quite a while which gives it a broader array of powers than other municipalities. 20 Municipal Authority (cont’d) Some of the powers that Vancouver has enjoyed include the ability, in using Official Development Plans for specific areas, to regulate the urban design and demand exactions and amenities from developers in excess of what other municipalities can do. They have made extensive use of these powers on the north shore of False Creek, and are using them in Southeast False Creek and elsewhere. Its charter was just expanded to enable it to borrow as much money as needed to salvage the Olympic Village. 21 Municipal Authority (cont’d) This reflects more of a British, as opposed to an American, approach to planning. Under the American system of zoning, once an area is zoned for a particular land use it is difficult to prevent a land use or development if it meets the zoning requirements. It is, in other words, permissive. Moreover, as our former mayor, Gary Korpan, was fond of pointing out, proponents can always apply to have specific parcels rezoned on their own merits. 22 Municipal Authority (cont’d) In the British system, local governments are able to make specific demands and impose specific regulations for specific sites. We won’t go into it today, but other legislation that is pertinent to land use planning in BC includes: the Regional Growth Strategies Act (incorporated in the LGA), the Land Title Act, the Strata Property Act, the Highway Act, the Agricultural Land Commission Act, and the Fish Protection Act. The best source of information on B.C. planningrelated legislation is William Buholzer, British Columbia Planning Law and Practice, available in the reference section of the library. 23 Other Actors In addition to municipal and regional governments, there are numerous other actors. These include: residents who live and work in the area industries and firms doing business there, and organized interest groups, such as ratepayers’ groups and neighbourhood associations, merchants’ associations, real estate boards, chambers of commerce, and non-government organizations devoted to environmental or social justice issues. 24 Other Actors (cont’d) A key group in the land use planning process is the development community, since planners and councils are often reacting to what developers are proposing. As Leung notes, a typical development process goes through five stages: conceptualization feasibility study design contract and construction, and marketing and disposal. 25 Other Actors (cont’d) Developers have multiple roles: promoter, negotiator, market analyst/ marketing agent, securer of financial resources, team manager, and entrepreneur. They commit equity, equipment, human resources, and managerial talent, and take risks in doing so. For them, “time is money,” whereas planners tend to be more cautious. On the other hand, in other ways developers (and their financial backers) are very risk-averse. 26 Other Actors (cont’d) The public is a key group (there are often many “publics”), and it often knows what it wants without knowing what kinds of trade-offs are involved or how complex the planning system can be. Nonetheless, the public can intervene and prevent major planning disasters from occurring, as has happened many times in the past (can you think of examples?). 27 Other Actors (cont’d) But the public can also often be motivated strongly by narrow self-interest and prejudice without seeing the “bigger picture,” and this is manifested in the so-called NIMBY and BANANA syndromes. What are some examples? Because of the complexity of planning and growth management and all the different players involved, planners must not only have technical knowledge, they must know how to communicate to different groups and facilitate their working together. Developers are also learning the value of this. 28 Changing Views of Planning The pendulum has swung in planning from physical determinism, to planning as if human needs outside the economy and having a home and a job were of little consequence (which produced a lot of ugly placeless development), back to a more balanced position that the physical environment is a key component contributing, positively or negatively, to human well-being. 29 Changing Views of Planning This leads to the need to plan proactively, rather than simply reactively, which has often been the dominant mode in the past. At the same time, it must be recognized that planners are not “free agents”. They either work for private developers or for municipal councils, and thus have to deal with “politics” and power. The best planners try to create their own power base, however subtly. 30 Class Project The main topics that we all expressed interest for the class project were: –solid waste; –innovative buildings; and –pilot projects. There was also discussion about improving the public realm and I asked you to review the Campus Master Plans documents to see how well they address some of these issues. Do you have any comments on the strengths and weaknesses of those documents? Let's also do a brainstorm on whether the three areas of interest have some potential synergies. 31